Wolves killing livestock was expected, but is there room for improvement?

This article is part of ongoing production for an episode of Colorado Experience about the history and reintroduction of gray wolves in the state. Follow along for behind the scenes content and updates on the episode.

EAGLE COUNTY, Colo. — Standing in a valley amid their cattle and surrounded by mountains and blue, spring skies, Sarajane and Travis Snowden are worried.

“We lose sleep,” said Sarajane. “I don't want it to be any of our neighbors. I don't want it to be us.”

The Snowdens fear that the December 2023 reintroduction of gray wolves into Summit and Grand Counties will put their ranching business at risk.

“This is our livelihood,” said Travis. “Once a year we get one paycheck from these cows.”

The Snowdens run a mid-to large-size, cow-calf operation in the Yampa Valley, about an hour’s drive south of Steamboat Springs. They focus on managing cows that give birth every year and the newborn calves until they are weaned and then sold off.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) released 10 young, healthy gray wolves captured from Oregon into Summit and Grand counties following passage of a state statute mandating wolf reintroduction.

CPW didn’t report where exactly it released the wolves and only announced ahead of time the first release of five wolves. In the days following that December 18 release, CPW released an additional five wolves at undisclosed locations.

“A week later we heard them,” said Sarajane Snowden, “we heard one howling from our bedroom, and I guess a lot of distrust started right then.”

From mid-April through May, the Snowdens run their cows on privately-owned land they lease during calving or birthing season. They live in a cabin on the property so they can stay close and check the cows every couple of hours. They’ll look for medical issues and tag newborn calves with ear markers to help keep track of them.

“Right now, I wish my only focus was, ‘how could I grow a healthier, better calf that will enter the food supply chain and flourish?’ I wish that was the only thing I had to worry about,” Sarajane Snowden said.

This year, things are different. Travis said every flash of something dark on the horizon causes his head to whip around to make sure it’s not a wolf.

So they have invested in a new side-by-side vehicle with a heater, so they can stay out in the herd even on colder nights. The Snowdens also hired their first full-time employee, a range rider, Dakota Cook.

Cook starts early in the mornings, moving in and out of the herd on horse-back to check on the cows and spread the human-scent. The Snowdens heard the smell and presence helps deter wolves.

Still, it's a big expense.

“I would much rather put that money somewhere else than fighting off a predator that we never had problems with for the last 30, 50, 100 years,” said Sarajane.

Before reintroduction in 2023, Colorado had a few gray wolves, or canis lupus, who had wandered into the state from Wyoming, which has a more robust wolf population. But, prior to that, wolves hadn’t lived in Colorado since the 1940s.

Wolves once roamed across North America but as settlers moved West and introduced agriculture, ranchers offered bounties for them. By 1892, hunters, or wolfers, killed an average of more than 10,000 wolves and coyotes each year in Colorado.

By the early 1900s, it became federal policy to eliminate many predator species, including wolves, so that they were practically wiped out by the 1940s.

“I think there's a reason that when the settlers came out here that they got rid of the apex predator, and I just don't think that they're a friendly [animal],” said Sarajane Snowden.

An apex predator is an animal at the top of an ecological pyramid whose presence has ripple effects down that pyramid. That impact throughout an ecosystem was the argument for returning wolves to Colorado.

In places such as Yellowstone National Park, where wolves were reintroduced in the mid-90s, Colorado State University researchers reported that wolves likely contributed to willow and aspen recovery and overall habitat diversity by reducing overbrowsing by elk.

Other western states, including Wyoming, Idaho and Montana, have both sustainable gray wolf populations and successful ranchers. Ranchers like the Snowdens and supporters of re-introduction alike look to those states for advice, direction and lessons learned in balancing wolf lives with Ranchers' livelihoods.

Naturist and taxidermist Edwin Carter from Breckenridge stands next to a taxidermized wolf taken from the Colorado Rockies. Photo: History Colorado Special Collections.

Paws on the ground in Colorado

“Wherever wolves and livestock or ungulates share the landscape, there's going to be depredation. That's just what wolves do, they’re carnivores,” said Eric Odell, the CPW wolf conservation program manager.

CPW defines confirmed wolf depredation as “physical trauma resulting in injury or death.”

Since the 10 new wolves were brought to Colorado, CPW has confirmed seven instances of depredation involving nine calves or cattle.

To confirm a wolf killing, CPW sends officers to gather evidence such as photographs, scat, tracks, attack and feeding characteristics, puncture wound spacing, etc.

Through the Wolf Depredation Compensation Fund, ranchers are able to apply and receive up to $15,000 for fair market value of livestock lost to wolf attacks. As established through a bill passed last year, the state treasurer is directed to transfer $350,000 from the general fund to the Wolf Depredation Fund each year. Odell said this money can also include veterinarian costs or a sliding-scale payout if there are missing livestock at the end of the season.

CPW asks ranchers who want to start a claim to first contact their local CPW office, preserve any evidence and take photographs. CPW said “wildlife officers are well-trained to carefully examine the scene where livestock died and determine the cause of death. CPW livestock depredation investigations are critical if a livestock producer is to be reimbursed for a loss.”

Eric Odell is the wolf conservation program manager with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, a position that didn’t exist before the ballot initiative passed. Odell has worked for CPW for more than 20 years. Photo: Amanda Horvath, Rocky Mountain PBS.

“We do what we can, understanding that money isn't going to buy all the social tolerance, but we do our best to make those producers whole,” said Odell.

The Snowdens believe the up-to-$15,000 market value for loss of livestock is a reasonable amount for wolf depredation. However, they argue, other factors are hard to calculate — such as their own anxieties and added strain to the cattle, which can impact their health.

“Cows don't do well being stressed. That's why we work really hard to give them a very happy, easygoing, awesome life in a cow-calf operation,” said Sarajane Snowden.

CSU’s Center for Human-Carnivore Coexistence (CHCC) confirmed Snowden’s observation, producers can suffer indirect losses due to wolves such as “stress, sickness, and reduced weight gain and pregnancy rates.”

Conflict, Coexistence and Communication

The CHCC and CPW emphasize a wide-range of management tools to reduce conflict ahead of time, including things that the Snowdens have implemented, like hiring Cook, their range rider.

Another idea is using fladry, or red flags, around the property perimeter to deter wolves. The flags work because wolves are neophobic, or afraid of new things. Unfortunately, the Snowdens have too much cattle grazing land for that method to work.

Another popular tool is to change cattle management to bring the cows closer together in a group formation that makes it less likely for a wolf to attack. But Sarajane said keeping cows too close together could jeopardize their health.

“Honestly, we think we're managing our cattle the best that we know how to do,” she said. “And through our mentors and through generations of practice, we're going to continue to do that.”

The Snowdens operate a mid-to large-size cow-calf operation in the southern Yampa Valley. In the spring, cows are giving birth and stay close to headquarters but soon will be moved up in elevation and spread out even more.

Photo: Jeremy Moore, Rocky Mountain PBS.

There are a number of other practices ranchers could enact to deter wolves, but one that the Snowdens said ranchers would like more flexibility with is the lethal option.

This is where the wolf-rancher balance gets legally complicated.

Currently, gray wolves are listed as an endangered species on the federal and Colorado species lists. This makes “take” of wolves illegal, meaning no chasing, harming, harassing or killing the wolves.

But in order for CPW to have management capability over the wolves, a 10(j) rule was enacted so deputized wildlife officers have the option to change the behavior of wolves if they are chronically killing livestock. Although the rule empowers CPW to kill predatory wolves if a case calls for it, they also use other non-lethal methods, including chasing them away.

“In the meetings with stakeholders and livestock producers, understanding that they really were concerned about how they could protect their interests, having that 10(j) rule was really critically important to do that,” said Odell with CPW.

“Otherwise, it's a completely endangered species,” he said.

CPW prioritizes other management practices before killing a wolf. Ranchers and citizens are not allowed to kill a wolf under the 10(j) rule.

The only legal way a rancher could kill a wolf in Colorado is if they witness the animal attacking livestock. Even then, CPW must confirm this act before it would consider issuing a “lethal take permit,” the verbiage they use for killing of a wolf. Penalties for illegal wolf killings in Colorado can vary but include fines up to $100,000 and jail time.

Most states consider killing a wolf after recorded cases of “chronic depredation,” meaning the wolf has been found responsible for the deaths of multiple livestock. However, CPW has not defined what number of livestock deaths it uses to classify chronic depredation, and Odell said that was on purpose.

“The guidance that we got from [the working groups] almost universally was that we should not come up with that metric [of] this number of depredations in this period of time,” he said. “They said, ‘let's give it time. Let's learn what it's like to live with wolves in Colorado and we'll see.’”

Gray wolves, or canis lupus, and its subspecies once roamed all across North America. With reintroductions in other states and now Colorado, the species could have continuous populations from the northern to the southern United States. The wolf pictured above lives at the Colorado Wolf and Wildlife Center in Divide.

Photo: Amanda Horvath, Rocky Mountain PBS.

While developing the 261-page Colorado Wolf Restoration and Final Management plan, CPW formed two groups that advised the CPW commission and staff on the plan. The Technical Working Group included heads of other wildlife departments, county commissioners and wildlife biologists and the Stakeholder Advisory Group included an even wider group of people including range scientists, county commissioners, zoo owners and operators, ranchers, outfitters, hunters and more.

The CPW commission unanimously approved the final wolf management plan in May 2023.

Other northern Rocky Mountain states that have both wolves and livestock producers have more flexibility than Colorado because they allow legal wolf hunting.

For the Snowdens, the best response to a wolf killing livestock would be to lethally remove that wolf.

“I personally don't want lethal control for myself because I don't want to be put on the line and then to be questioned,” said Sarajane Snowden.

“Our understanding from the neighboring states is that once they learn to kill your livestock – it's just like with a bad coyote or a bad bear – they continue to be a problem,” she said.

CPW said it has received and responded to multiple livestock producer associations letters asking the agency to kill two wolves in Grand County that have been responsible for depredation.

One response to the Middle Park Stockgrowers Association from Jeff Davis, the director of CPW, said it would be “irresponsible management” to remove the wolves at this time. Davis cited the number of wolves is well below the restoration goal for the wolf population and that CPW believes the animals are denning or expecting pups and killing even one of the parents could cause the den to fail.

“Colorado Parks and Wildlife is taking the responsibility to establish a wolf population very seriously,” said Odell in an interview before the first wolf depredation was confirmed this year.

“We're doing the absolute best that we can do. We're doing a very science-based approach to this, science-based in the terms of what this species needs and science-based in terms of what we have learned from the public and what is the human side of wolf management,” he said.

In December 2023, CPW successfully captured and released 10 healthy gray wolves from Oregon onto the Western Slope of Colorado.

Photos courtesy Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

Out of the 10 wolves reintroduced in December, nine are still alive. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is investigating the death of one in Larimer County and initial evidence suggests the wolf likely died of natural causes.

Odell said to begin the process to downlist gray wolves from endangered to threatened in Colorado, at least 50 wolves must live here for four years.

The Snowdens would likely never support reintroducing wolves back into this landscape and wish the ballot measure hadn’t passed but they’re also of the mindset that there’s no use crying over spilled milk.

“The wolves are here. They're introduced. I feel like now we're at the point where we need to learn to manage it,” said Travis Snowden.

For the Snowdens, that means they want better communication from CPW. They said they’ve seen CPW helicopters flying overhead and will often see wildlife officers driving around in marked vehicles and stop to ask if they’ve seen wolves recently and be told, “no.”

Sarajane Snowden also said they were told to call with questions and concerns but that when she’s done so CPW won’t answer the phones.

“I don't feel like they're working with us as a team right now, and so I feel like a lot of ranchers and private landowners are going to stop being as cooperative,” she said. “And we're a huge piece in wildlife management.”

CPW public information supervisor, Travis Duncan, told Rocky Mountain PBS in an email statement that CPW staff are notifying livestock producers when wolves are in the area. Duncan explained the notifications are given to “community-designated livestock producers with phone trees” who are then calling other producers to let them know.

Duncan with CPW also clarified that CPW biologists use helicopters for a variety of management efforts and it was very likely what the Snowdens saw was unrelated to wolves. He said “we have not employed helicopters for wolf management in the area described. The CPW staff that were contacted likely are not involved in wolf management.”

Ultimately, when there is a lack of information and fear, like in the case of wolf reintroduction, the mind can fill it in with assumptions. That’s where the Snowdens want more communication from CPW. But Odell wants to make something clear to Coloradans that striking the balance between protecting the vulnerable wolf population and interests of ranchers is an ongoing process. But, he said, the goal is to respond to criticism while supporting reintroduction.

“We're not doing anything under the cover of darkness. We're not doing anything shady at all. We're doing what we can to restore wolves, to protect wolves, and to address the concerns and the impacts that people are going to sense and [are] going to feel from having wolves on the landscape,” Odell said.

“We're doing the best that we can with it. Mistakes will be made and we'll learn from those mistakes and we'll move on. But it's a very intentional and purposeful effort that we're taking on.”

Locations not immediately available

The 10 Oregon wolves CPW reintroduced were made up of six females and four males. Two of them were adults and the other eight were yearlings, which means they were born in the spring of 2022. Wolves aren’t considered adults until two years of age.

Wildlife officers collared each of the wolves with GPS trackers. Odell said these collars use satellites to show where each wolf has traveled in the last day but the system doesn’t work like the GPS on our phones.

“The way the GPS works is that it gets a point every four hours and then the collar itself stores those points and then communicates that back up to a satellite and then that communicates to us,” said Odell. “About a 16 or 20 hour period, we get four or five points communicated to us, but that can vary by weather or terrain.”

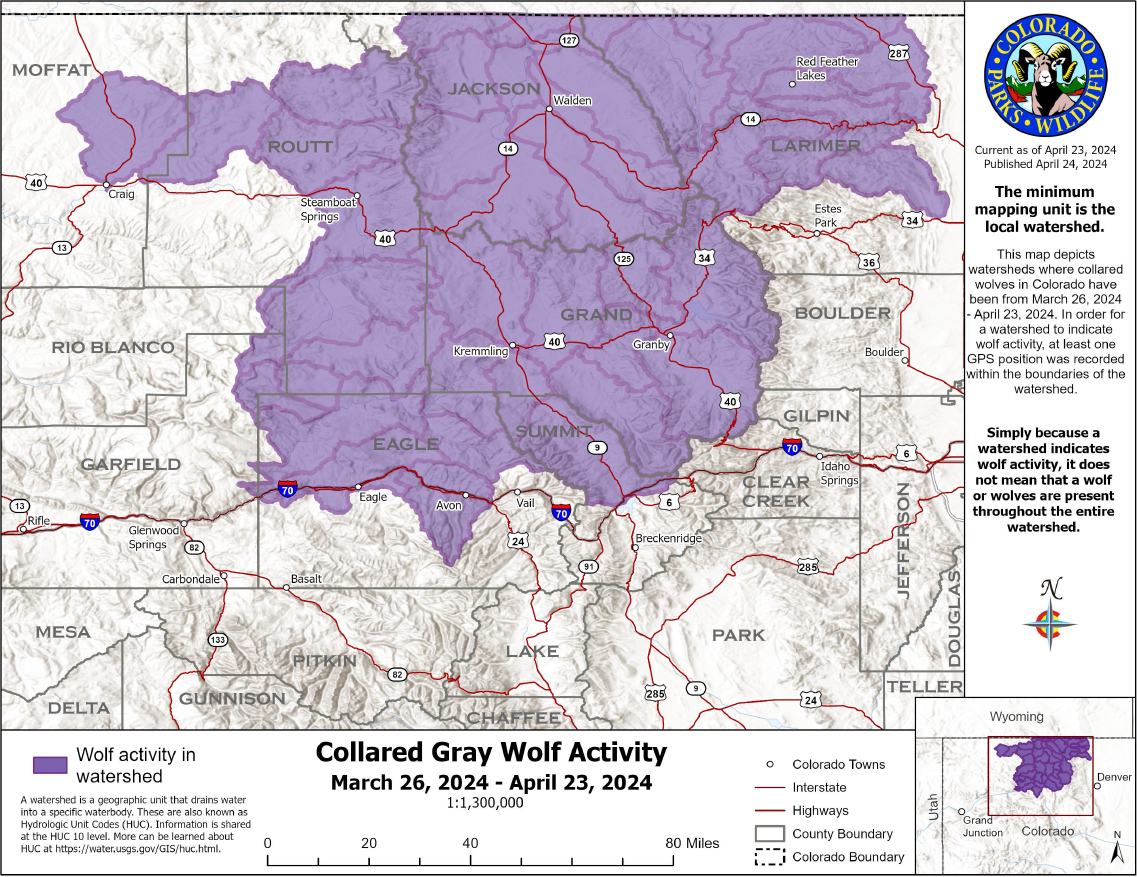

Each month, CPW provides an update on wolf location activity to give people a sense of the area the animals are moving. They do have more accurate location information they withhold out of safety of the animals but the maps they release show the watersheds in which the wolves have been active in the last month. A watershed refers to a land area that channels rainfall or snowmelt to a specific body of water.

The latest map of activity from March 26 to April 23 highlights the watershed the collared wolves were tracked in, which for the first time pinged in a watershed on the eastern side of the Continental Divide. CPW also said two of the collars were not functioning but officers were able to confirm those wolves are alive via plane surveillance.

“The intent of those collars is really to show – where in the state are they? Where are they moving around? Are they still alive? Who are they traveling around with? Those kinds of things,” Odell said.

“It's not to say, ‘Okay, it's on this ridge, that the west side of the ridge now is crossing the east side of the ridge,’” he said.

The Snowdens said they aren’t interested in the exact location of the wolves but believe ranchers operating on privately-owned land have a right to know about where they are.

“I wish there was just greater clarity on the location of these animals, where they're at, how their health is,” said Travis Snowden. “I feel like those are things we need to do to understand because we are directly affected.”

Sarajane Snowden also worries that if the wolves establish themselves too close to ranchers now, they’ll always be a problem.

“If they won't settle here, then they won't settle here. But if they get comfortable here, then [for] the next ten years we're going to just see a growing problem, especially if we're not allowed lethal control,” she said.

Sarajane and Travis Snowden are multi-generational cattle ranchers who made their dream a reality by starting their own cow-calf operation in 2020.

Photo: Alexis Kikoen, Rocky Mountain PBS

Springtime is one of the most likely times of year for wolf depredation to happen, according to Odell. Wolves are opportunistic hunters and tend to look for easier prey, often the very young, old, sick or injured wild herds. But young or newborn calves on cattle ranches unfortunately make for good targets.

The Snowdens are mainly concerned with this time of year and the beginning of the summer when they let the cows and their young calves graze at higher mountain ground. Even with a range rider, some of those cows won’t be checked for potentially a couple of days.

In sharing her story, perspective and ranching operation Sarajane hopes that those who aren’t on her side potentially understand her better.

“The rural-urban divide has some friction and I think [the wolf issue] added to that friction a ton,” she said.

In 2020, Colorado voters narrowly passed Proposition 114, which mandated wolf reintroduction, with most of the popular vote coming from urban settings. The counties that had more than 50% who voted “yes” to the reintroduction of wolves included Larimer, Boulder, Broomfield, Jefferson, Denver, Adams, Arapahoe, El Paso, Summit, Pitkin, San Juan and La Plata.

Sarajane and Travis Snowden said they’ve talked with people who voted for wolf reintroduction and those conversations were sometimes good, some admitted they didn’t understand what they voted for, and others said they still support wolves but wish there was more support for ranchers.

But some conversations have just been too hard.

“I probably am not going to put myself in those situations to visit with them anymore because they're not going to change my mind, and I'm not going to change their mind. And I think that that's just the way that one is,” said Sarajane Snowden.

Still, the Snowdens have hope Coloradans can come together and believe the course for the next decade will be set now.

“I hope in the future we can kind of get past this point of I'm on this side, I'm on this side,” said Travis. “I'm optimistically saying we'll get there, and that we'll get to the point where everyone works together.”

“We need to support agriculture or you're going to be naked and hungry,” said Sarajane.

Amanda Horvath is the managing producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. amandahorvath@rmpbs.org.

Melanie Towler is the video editor at Rocky Mountain PBS. melanietowler@rmpbs.org.