A tale of two towns: The clash between LGBTQ+ supporters and opposing groups in Montezuma County

CORTEZ, Colo. — Lance McDaniel thought a box of pizza for a small group of LGBTQ+ Montezuma-Cortez Middle School students and their allies would help put a smile on the children's’ faces.

For months, McDaniel, then a member of the Montezuma-Cortez Board of Education, delivered pizza under the anonymous title “the pizza fairy” to the middle school’s Rainbow Club – a lunchtime opportunity for LGBTQ+ students and allies to gather in a safe space.

The move seemed innocuous to McDaniel — then the comments began flooding in.

Words like “groomer,” “pedophile” and “communist” started to fill the comments section under his Facebook posts, which largely consisted of liberal political commentary and school board notices.

McDaniel said he never received face-to-face threats, but some of his neighbors in the Four Corners-region school district continued their social media attacks after discovering he was “the pizza fairy.”

McDaniel and Monica Slabodnick — the Rainbow Club’s adult chaperone and a paraprofessional at Montezuma-Cortez Middle School — said McDaniel only came inside the classroom to meet the children in the club once, but that didn’t stop the vitriol.

Over the coming months, community members began filming him in public, McDaniel said. In October 2020, several people connected via Zoom to a school board meeting interrupted the meeting, and one person was heard threatening to rape McDaniel’s daughter, according to a news report by Cortez radio station KSJD.

Cortez Police Department Chief Vernon Knuckles told The Washington Post that the department was unable to determine who made the threats, and therefore unable to take action. Knuckles did not return calls for comment to Rocky Mountain PBS. According to the Post, Knuckles had earlier signed a petition seeking McDaniels' recall.

‘These kids need help’

After a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd in May 2020, McDaniel wrote “I’m antifa” on his Facebook page. To him, the phrase was simply a public condemnation of fascism, which he believed was on the rise after President Donald Trump’s 2016 election.

McDaniel said he also worried that fascism was on the rise in his own community, where a group known as the Montezuma County Patriots had circled a memorial for Floyd and played loud country music while trucks with American flags and thin blue line flags sped around.

McDaniel said his publicly stated liberal views often ran counter to those of his conservative neighbors and school board counterparts. In the 2020 presidential election, in which Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump, 60 percent of Montezuma County residents voted for Trump.

As a straight, cisgender, white man, McDaniel said he felt a sense of duty to stand up for marginalized members of his community, especially LGBTQ+ children, who he said have become a target of far-right attacks.

“These kids need help, and they deserve help and they deserve assistance in being themselves,” McDaniel said. “It’s just been very important to me.”

Two members of the Montezuma County Patriots declined to comment on behalf of the group. But Odis Sikes, a member of the group and candidate for Montezuma County Sheriff, recently told a group of attendees at a campaign event that he would put deputies in school board meetings to ensure teachers are not teaching critical race theory or LGBTQ+ issues.

[Related: At public event, Colorado sheriff candidate vows to implement anti-trans policies if elected]

While McDaniel was not shy about his liberal views, he said he believed his Facebook was representative of his personal views, not those of the school board. He also believed his views never impacted his decisions on the board.

But others in the community saw it differently.

In July 2020, Mindy Nelsen and Debbie McHenry, two county residents, organized a petition for a recall election to remove McDaniel from his school board seat.

Recall supporters said McDaniel had shown a lack of leadership and was a poor role model for students. McDaniel said the effort was started by conservatives who did not like his liberal views and who used “groomer” rhetoric to scare others in the community into recalling him.

By the October deadline for the petition, more than 1,600 voters signed off on the recall. McDaniel was then recalled in a February 2021 election by a 2-1 vote. Resident Cody Wells ran unopposed to fill McDaniel’s seat.

The Montezuma County Patriots does not have its own website and because two members from the party declined an interview, so it is difficult to discern what exactly the group believes, but several experts on right-wing extremism said Patriots groups are popping up across the country, and their beliefs are largely the same from group to group.

“The essence of their belief system is that the world is run by a sacred group of nefarious globalist conspirators who are trying to manipulate the world into enslavement,” said investigative journalist David Neiwert, author of “Alt-America: The Rise of the Radical Right in the Age of Trump.” “They’ve been fantasizing about civil war since the ‘90s, and it’s reached a head these days.”

Karrin Anderson, a communication studies professor at Colorado State University, said conspiracy theories and bigotry have always hidden under the surface of the Republican Party, but Trump’s election brought such talking points into the mainstream.

“Mainstream political actors on the right are kind of mixing extreme conspiracy theories or positions with mainstream ideas,” Anderson said. “Republicans are just becoming accustomed to hearing really extreme positions from their mainstream politicians and also from their friends and neighbors.”

Rachel Carroll Rivas, interim deputy director of research and analysis at the Southern Poverty Law Center’s intelligence project, said extremist groups like the Patriots have victimized LGBTQ+ people and their allies by claiming that they are hurting children.

“We see that attacks on LGBTQ people have used this idea of being threatening to children,” Carroll Rivas said. “It’s completely false. It’s not based on facts; it's just an old tactic that’s been used to attack communities and ‘other’ them throughout history.”

Real-world consequences

While middle school years may be difficult for most people, being a 14-year-old transgender boy at Montezuma-Cortez Middle School in a rural, mostly conservative area had been particularly difficult for Jack Hough.

Hough said many of his teachers refused to use his name and pronouns. The first time could have been an honest mistake, he said, but after several corrections from himself and his mother, Hough believed the teachers should have done a better job at trying to be respectful.

“At first I was sad, but when it kept happening, I got more mad,” Hough said. “It just sucked.”

Hough took comfort in knowing there was one place he could escape the bullying and be surrounded by kids and a teacher who respected him and his identity: Monica Slabodnick’s Rainbow Club.

Slabodnick, a now-retired paraprofessional at the middle school, started the Rainbow Club in 2017 after a group of kids approached her and asked if she’d be willing to start a lunchtime club for LGBTQ+ students and allies. After a year of back-and-forth communication with the school board and school administrators, the club finally took off.

Students in the club could drop by, eat a slice of pizza and enjoy 30 minutes to be themselves without fear of being bullied.

“They were sweet, innocent kids who just wanted to hang out and feel supported,” Slabodnick said. “We have a good amount of faculty on board who do not actively support these students, and the kids are astute enough to figure out pretty quickly who is and is not supportive to them.”

Throughout the club’s first year, Slabodnick said she was bombarded with questions from other teachers about how kids could understand their identities at such a young age and accusations that adults involved with the club were behaving inappropriately.

“I said, ‘This is middle school. They’re exploring, they’re questioning, they may not be gay, but many of them just want to support [their LGBTQ+ classmates] and let you know that if you are gay, they’ll be your friend,” Slabodnick said.

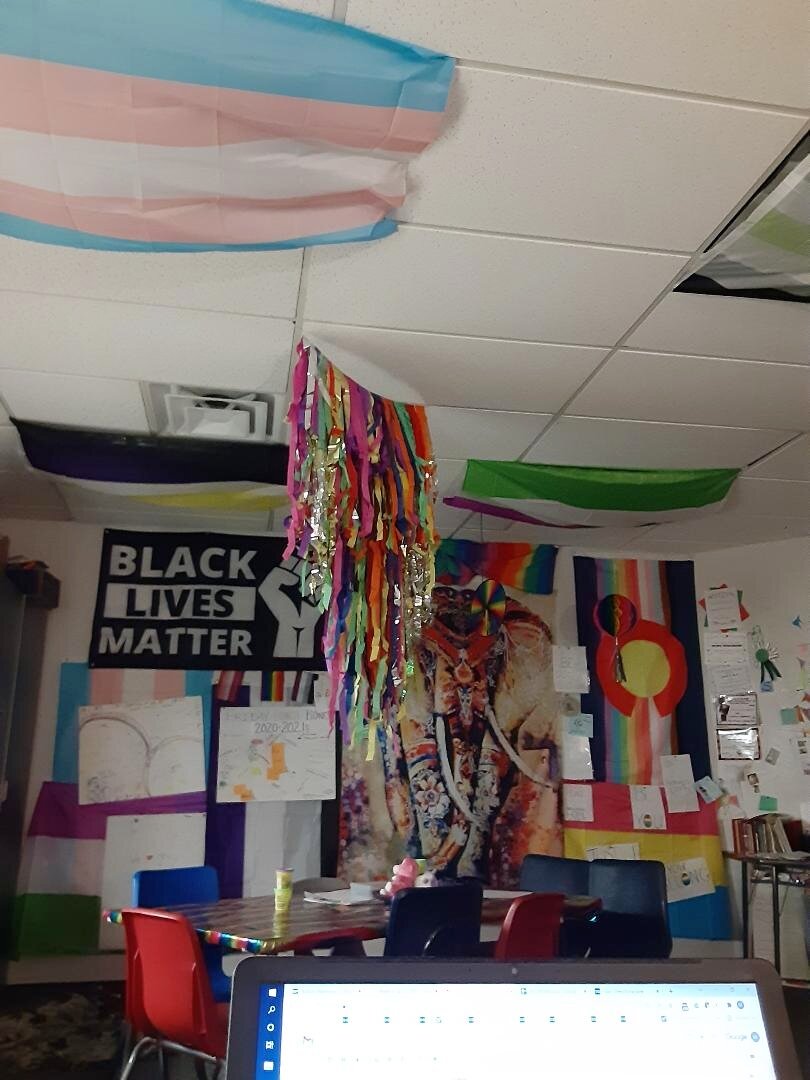

Slabodnick hung up a transgender pride flag, a bisexual pride flag, several generic rainbow flags and a sign that read “Black Lives Matter” in the classroom where the club met.

Shortly after putting the flags up, Principal Drew Pearson asked Slabodnick to take them down, claiming the school’s superintendent and the school district’s attorney recommended teachers “not have such items in public areas of the building,” according to emails between Pearson and Slabodnick obtained by Rocky Mountain PBS.

Slabodnick then told Pearson that she had face-to-face meetings with every other teacher who used the room and they agreed to use other classrooms, so Slabodnick left the flags up.

After leaving school on Jan. 13, 2021, Slabodnick said she noticed the flags were removed from the wall, and Pearson had taken them down. Pearson later referred to the flags as “inflammatory icons,” according to the emails.

In an email to Slabodnick, Pearson wrote:

“I had multiple complaints from staff yesterday in a team meeting. As you and I discussed previously this year, after my conversation with the Superintendent, Asst. Superintendent and our school attorney it was determined these type of “inflammatory icons” are not to be placed in common places in the building. This is a shared space and not your room therefore it would qualify as such."

“I will ask again that you refrain from placing these items in public locations within the school. I understand that this is supportive of the ideals of your group, but it is not of the ideals of all students or adopted ideals of the district as approved by the board of education,” the email continued.

Sara Neel, a senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado, said whether or not Pearson asking Slabodnick to take the flags down is legal depends on if the school prohibits flags with any sort of messaging, or only flags showing LGBTQ+ support.

“If the school is saying everyone who has a pride flag must take those down, but other teachers have flags displayed that are supportive of other issues, that could be a First Amendment violation,” Neel said. “Teachers certainly don’t leave their First Amendment rights at the door, and the government can’t tell people to relinquish their rights as a condition of being a public employee.”

Pearson declined to comment on the flags, and forwarded an interview request to Superintendent Tom Burris.

Burris declined to grant a phone interview, but wrote the following in an email:

“Montezuma-Cortez School District utilizes a nondiscriminatory practice with regard to classroom displays. Staff members are permitted to have small mementos and images in their personal workspace. However, such items are limited in size, and personal expressions such as flags, posters, and the like are not to be distracting or intended to influence or disrupt classroom activities.”

Related Stories

Regardless of whether the move was legal, Neel said removing the flags is cruel, especially in a small, rural area where LGBTQ+ kids desperately need support.

“The bottom line is it’s not a good policy for a school to be doing this,” Neel said. “Policies like this are really kind of tragic, because they’re targeting kids who are just trying to be themselves and really need support from their community.”

After Slabodnick retired in 2021, another teacher took over the club. The teacher, who asked not to have their name used in this story for fear of retaliation from parents and administrators, received an email from a school district employee Sept. 15 telling them that the school board passed a policy that limits the ability for student-led or student-initiated clubs to meet during lunchtime, as the time is counted as instructional time.

The email, which was forwarded to Rocky Mountain PBS, said clubs not officially sponsored by the school — including the Rainbow Club — would need to meet before or after school.

“That’s a problem for students whose parents don’t know that they’re part of the LGBTQ community and would need to take them to school early or pick them up late,” the teacher said in an interview. “It’s a safety risk from their families and their community.”

A board of controversy

In January 2022, Board of Education President Sheri Noyes asked former Superintendent Risha VanderWey to resign and asked board members to be silent about the “logistics” surrounding her departure, according to reporting from The Journal, a newspaper covering Cortez and the Four Corners region.

Noyes and board members said in emails to parents that the decision had nothing to do with political differences, though VanderWey is a registered Democrat and six of the seven board members are Republicans, with member Cody Wells not registered to a party, according to voter records from the Colorado Secretary of State’s office.

None of the seven board members responded to several emails and phone calls from Rocky Mountain PBS.

Despite telling parents that the decision to remove VanderWey was not political, the Montezuma-Cortez School Board has had a history of encounters with controversial political issues, from McDaniel's recall to board members resigning over disagreements.

In September 2021, members Chris Flaherty and John Schuenemeyer resigned from the board, citing disagreements about mask-wearing and critical race theory.

Weeks before the two men resigned, the board approved a motion called “Resolution Opposing Principles of Critical Race Theory,” and established a committee to search school curriculum and remove traces of critical race theory that it found to be “embedded,” according to school board meeting minutes and video recordings. critical race theory refers to college-level courses that are not typically taught in K-12 schools.

A county divided

According to data from the United States Census, Montezuma County’s racial demographics are 71.7% white-alone, 14.3% Native American and 12.8% non-white Hispanic or Latino.

However, every member of the school board is white, which Indigenous people in the area said is an issue.

“We’ve been here since the beginning of time, and we don’t get that consideration in our schools,” said Gina Lopez, who is Indigenous. “This is our land. It’s stolen. Where else would we go but here?”

Lopez has a queer child in the school district and said she has spoken to the school board three times, asking them to provide more support for her child and those like them. Lopez said her child has dealt with depression and suicidality due to their identity, and the Rainbow Club was one of their only options for safety. Without the club, Lopez said her child would be even further ostracized in the school.

“We can’t continue to create this intolerance, because we will lose children,” Lopez said. “If it’s not suicide, it will be violence.”

On top of her child being a part of the LGBTQ+ community, Lopez said being Indigenous in the area has created its own set of problems, with racism from teachers and other students.

“It’s not only that our kiddos are LGBTQ, it’s that they hold different cultures that aren’t being given any weight or space,” Lopez said. “Our little ones shouldn’t have to fight these battles.”

Though Colorado touts itself as a progressive state, Lopez said rural areas like Cortez have their own versions of “Don’t Say Gay” bills and racist policies.

“What we see happening in Florida with ‘Don’t Say Gay,’ we’re seeing that happening here in Colorado in these small pockets because these counties are left to decide for themselves,” Lopez said. “As a state, I don’t think this is what we want to be known as.”

[Related: ‘Don’t Say Gay’ law brings worry, confusion to Florida schools]

Pushing back

Another employee of the school, who has a son who is part of the LGBTQ+ community, has also decked out her office with rainbow flags, showing support to her son and all who enter the office.

The employee asked not to be identified for fear of backlash from the community, which she said she has received for having the flags on public display.

“My vision is to help and encourage and support no matter who these kids are or what they identify as,” the employee said. “If my son wants to bring his purse to school instead of a backpack, he should be able to do that.”

The school also had its first LGBTQ+ Pride event in 2019, and parents of LGBTQ+ children said they have a small-but-mighty coalition of straight, cisgender allies ready to defend queer community members.

“These kids need an atmosphere of kindness,” said Janet Hough, who has two queer children in the school district.

Hough and other allies refer to the Montezuma County Patriots as the “Hateriots,” because of what they see as bigotry coming from the group.

“Every time those people act up and they do things that aren’t right, no one is ever held accountable for that behavior,” Hough said. “I do hope enough people care about these kids to change some things, because we need consistent efforts.”

A nationalized issue

More than a dozen community members and political experts interviewed for this story agreed on one point: the Montezuma-Cortez Board of Education and its political dealings are a microcosm of a problem across the country.

“Cortez, I think, is experiencing an example of what we're seeing in various places around the country,” Carroll Rivas, the Southern Poverty Law Center official, said. “The hard right targets those local races.”

“This type of activity continues to escalate. After the Jan. 6 insurrection, we saw a shift in focus to the local level, and it’s had enormous impacts,” said Lindsay Schubiner, momentum program director for the Confronting White Nationalism in Schools program of the Portland, Oregon-based Western States Center. “In this shift to local organizing, a lot of that has targeted local government, particularly school boards.”

Philip Gorski, chair of the sociology department and co-director for the Center for Comparative Research at Yale University, said school board members who’ve led anti-critical race theory efforts have a goal of teaching inaccurate versions of American history.

“They want to control the way that American history is taught,” Gorski said. “It’s wanting a mythological, white-washed version of history to be taught in which white people are the heroes.”

Schubiner said right-wing extremists have specifically targeted school boards to push far-right narratives about people of color and LGBTQ+ kids early into students.

“This absolutely has an impact on how young LGBTQ people or young people of color are able to learn,” Schubiner said. “They’re making schools less-inclusive learning environments.”

Several community members agreed with the statements about political pandering and felt children getting trapped in the midst of adult fighting was an unfortunate side-effect.

“I think they’re putting our children at a definite disadvantage. They’re doing all this political maneuvering at the expense of our children's education,” said Mike Lavey, former mayor of Cortez. “We can’t turn our backs on these kids.”

Alison Berg is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alisonberg@rmpbs.org.

After Monica Slabodnick hung LGBTQ+ Pride flags in the classroom where the Rainbow Club gathered, the school's principal, Drew Pearson, referred to them as "inflammatory icons" and had the flags removed. Pearson declined to comment on the flags to Rocky Mountain PBS.