‘The godmother of the West Side’: How one Colorado Springs unhoused woman carries a community

This story is the first of several in a Rocky Mountain PBS series documenting homelessness in Colorado Springs. As the topic is debated by politicians and mayoral candidates promising solutions, those living in it share their stories.

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — Amy Goldsbury’s smile reaches both corners of her face. Her light brown hair is freshly dyed and constantly brushed. Sparkly, golden eye shadow decorates her olive green eyes on days she feels like dressing up. On April 17, a gray hoodie covers her head as she trudges through rain thumping over a muddy trail on Colorado Springs’ west side on a cold day.

About a quarter-mile into the trail, Goldsbury takes a left turn down a steep dirt path. She climbs down about six feet to greet her boyfriend, Nicholas Shepard, at the couple's shared campsite. Like many cities, Colorado Springs doesn’t allow outdoor camping, so Goldsbury and Shepard have a hidden spot away from cops, other unhoused people and anyone else who could pose a threat.

“I got you something, babe,” she tells Shepard, tossing him a quarter-ounce bag of weed. “It’s a present.”

Colorado Springs does not permit the recreational sale of cannabis, but Goldsbury knows a guy. In fact, she knows nearly everyone living outside on her side of town.

Goldsbury’s popularity reached a new level in the past year, so much so that she’s dubbed herself “the godmother of the west side.”

“I could be the one to take over things in the homeless community if need be,” Goldsbury said. “Everybody listens to me out here on the West Side.”

A trying journey

Goldsbury is from Kansas. She moved to Colorado 26 years ago with an abusive ex-boyfriend, who she broke up with in 2019. The two lived together in Fountain before she ended their relationship, as decades of abuse pushed her to the brink.

Her first several months alone were supported by stimulus checks issued at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, which she used to stay in motels across the Pikes Peak region. After that money ran out, Goldsbury landed on the West Side, between I-25 and 31st Street.

“I risked everything when I left,” Goldsbury said of the relationship. “But I don’t regret one thing.”

Goldsbury prefers the west side of town for several reasons: Westside Cares — a social services organization — is nearby and provides her with bus passes, food and clothing. Visitors headed to Manitou Springs also pass through Colorado Highway 124 — which runs along the West Side — and are sometimes generous enough to drop her a couple bucks while she flies a sign. The backdrop of Front Range foothills and silhouette of Pikes Peak also help her feel grounded.

But mostly, this is where she found community.

“These guys have basically adopted me,” Goldsbury said of longtime West Side campers. “I have more friends out here than I’ve ever had in my life, and I’m grateful for all of them.”

Living outside presents different challenges every day for Goldsbury. If it’s not police, it’s other homeless people. Snow. Powerful winds. Harassment from nearby drivers. But it’s always something.

Though her life often feels like a never-ending uphill marathon, Goldsbury maintains an unusually pleasant demeanor, much more so than others living on the street dealing with brutal conditions.

“She tends to see things with a degree of optimism that’s sort of uncharacteristic of people in her situation,” said Kristy Milligan, CEO of Westside Cares, a social services organization Goldsbury frequents. “She’s a bright light. She approaches her tasks with diligence, and I’ve never heard her say anything negative about anyone.”

Westside Cares hosts quarterly cleanups at Vermijo Park — where Goldsbury often hangs out and many unsheltered people camp. Milligan said it’s common to see more unhoused than housed neighbors at such cleanups, and Goldsbury never misses a beat. She picks up trash, guides others and does it all with a bright smile, Milligan said.

Reputations

Goldsbury gave herself the “godmother” title because of what she sees as an ability to diffuse conflict and brighten days.

“When I walk into the park, any disagreements going on just dissipate, " Goldsbury said. “It’s like a weird ability I have.”

“The park,” Goldsbury refers to is Vermijo Park, a small, grassy area in Old Colorado City, with Fountain Creek bisecting the park. Two basketball hoops sit on one side, with a playground and parking lot on the other.

Unhoused community members frequent Vermijo Park. They clean up trash from other park-goers and enjoy one of the last spots in the city to sit and relax for free without breaking any laws.

Others around the West Side – both with and without homes – share varying views of Goldsbury.

“I’m mad at her because she caused me some drama,” said Carla Chris, another unsheltered woman on the West Side, in an April 20 interview. “But she’s a sweet lady with a big heart.”

Chris said the “drama” is inevitable at times. Living outside, fighting off criminal penalties, theft from other unhoused people and constant snark and harassment from those with more privilege drive neighbors to frequent conflict. But it usually resolves itself within a few days, Chris added.

Another homeless woman asking for money outside a Starbucks at 31st Street and Colorado Avenue, JoJo, described Goldsbury as “good people.”

“She’s sweet and she keeps to herself,” JoJo said. “She won’t rob you.”

Others on the West Side said Goldsbury is their go-to problem solver, both for housed and unhoused people.

“She's one of the leaders. I’ve heard her called an elder, I’ve heard her called a general,” said RayRay Durkey, a cashier at a West Side gas station Goldsbury frequents. “To me, she’s the heart and soul of the area; she has an incredible heart.”

Goldsbury doesn’t have regular cell phone access, so Durkey counts on her popping into the gas station to maintain their friendship. Sometimes to buy a disposable nicotine vaporizer for her boyfriend, sometimes to grab a snack or two. Often just to say “hello.”

“She’s meant a lot to me,” Durkey said. “She’s helped me get through a lot of stuff and she’s helped me do this job and do it well.”

Durkey has housing on the northeast side of town, nowhere near Goldsbury’s regular camp spots, so the two maintain friendship via the gas station. Goldsbury knows when Durkey works and the two spend time laughing, gossiping and solving problems.

“If someone is giving me trouble here, Amy takes care of it,” Durkey said in an interview between scanning customer snacks, pulling out packs of cigarettes and cleaning soda dispensers. “She’s my person.”

Durkey’s grandfather died in December, leaving her with feelings of emptiness, confusion and a deep depression.

“Amy reminded me that he made it safely to the other side,” Durkey remembers. “She wants the best for everybody. She wants to do what she can for people.”

An untraditional love story

After 25 years in an abusive relationship, Goldsbury questioned the prospect of finding love again. When she first entered homelessness, Goldsbury never imagined finding a stable relationship.

In 2019, while sitting in a camping chair in Vermijo Park, Goldsbury saw a man walk towards her from the other end of the park. Nicholas Shepard was mumbling to himself, his dark brown mop of curly hair covered his forehead, stopping just above his squared glasses. To others, the man may have blended into the crowd, but to Goldsbury, he was the most beautiful she’d ever seen.

“I’ll never forget how gorgeous he was,” Goldsbury said.

A friend in the camp chair next door dared Goldsbury to introduce herself. Goldsbury didn’t expect much, but knew she’d regret not giving at least an introduction.

Nearly four years later, the two are engaged.

“I never thought I’d fall in love again,” Goldsbury said. “Being out here is hard. But when we’re together, it’s kind of easy.”

The logistics of a white gown, tuxedo and flashy traditional wedding are difficult for the couple, who spend what little money they make from roadside donations on food and other necessities. Still, Goldsbury dreams of walking down an aisle and being legally bound to Shepard. Though a more formal event may be out of the question, the two are hopeful for at least a courthouse ceremony.

“We can’t live without each other,” Shepard said. “We’re codependent.”

Shepard, who has been on the streets for 11 years after serving nearly five years in the United States Army, has epilepsy, bipolar disorder and autism. His conditions make it nearly impossible for him to stay in homeless shelters.

“Jail is better than a shelter,” Shepard said. “At least you have your own space.”

Shepard served 120 days in the El Paso County Jail, with charges stemming from kicking down an elk statue in nearby Manitou Springs. He was originally sentenced to two years of probation for the offense, but didn’t comply with a term of his probation, landing him 120 days in jail for the violation.

Prior to his homelessness, Shepard was stationed at an army base in Oklahoma for nearly five years. He came to Colorado Springs by way of a girlfriend who left him after the two settled into town. He was granted housing years ago but was evicted after his utility bill failed to be paid by the organization responsible for paying it. Shepard said he was never contacted about the need to pay the bill and came home one day to a surprise eviction notice.

Shepard is still eligible for housing, though he’s never re-applied. The process feels too daunting, he said.

“I have no money. I don’t even have an ID, so I can’t get a job,” Shepard said.

Because of his epilepsy, Shepard holds onto Goldsbury throughout the night to try and avoid triggering a seizure. The couple is a team in the same way a housed couple may be. But instead of purchasing a house and raising kids together, the two sleep in shifts to fend against potential dangers, protect each other and hold tight for emotional comfort and physical warmth through sub-zero-degree nights.

“He takes care of me out here and he’s my best friend,” Goldsbury said. “Just by being here and not leaving. That’s all it takes.”

Survival mode

Just after the first beam of light rose in Colorado Springs on the dawn of April 20, Shepard and Goldsbury awoke to the startling knock of footsteps and blinding flashlights. The two had just fallen asleep hours before.

“You need to pack up and go as soon as possible,” Goldsbury remembers a Colorado Springs Police Department officer telling the two. Soon after, Goldsbury and Shepard left for hours to “fly signs,” — the practice of standing in a street median or outside a shopping center with a sign requesting money. When they came back, nearly all their belongings were gone.

A green foam mattress, an expensive sleeping bag shared between the two, pillows and sheets to make sleeping outside slightly less awful, all gone within hours.

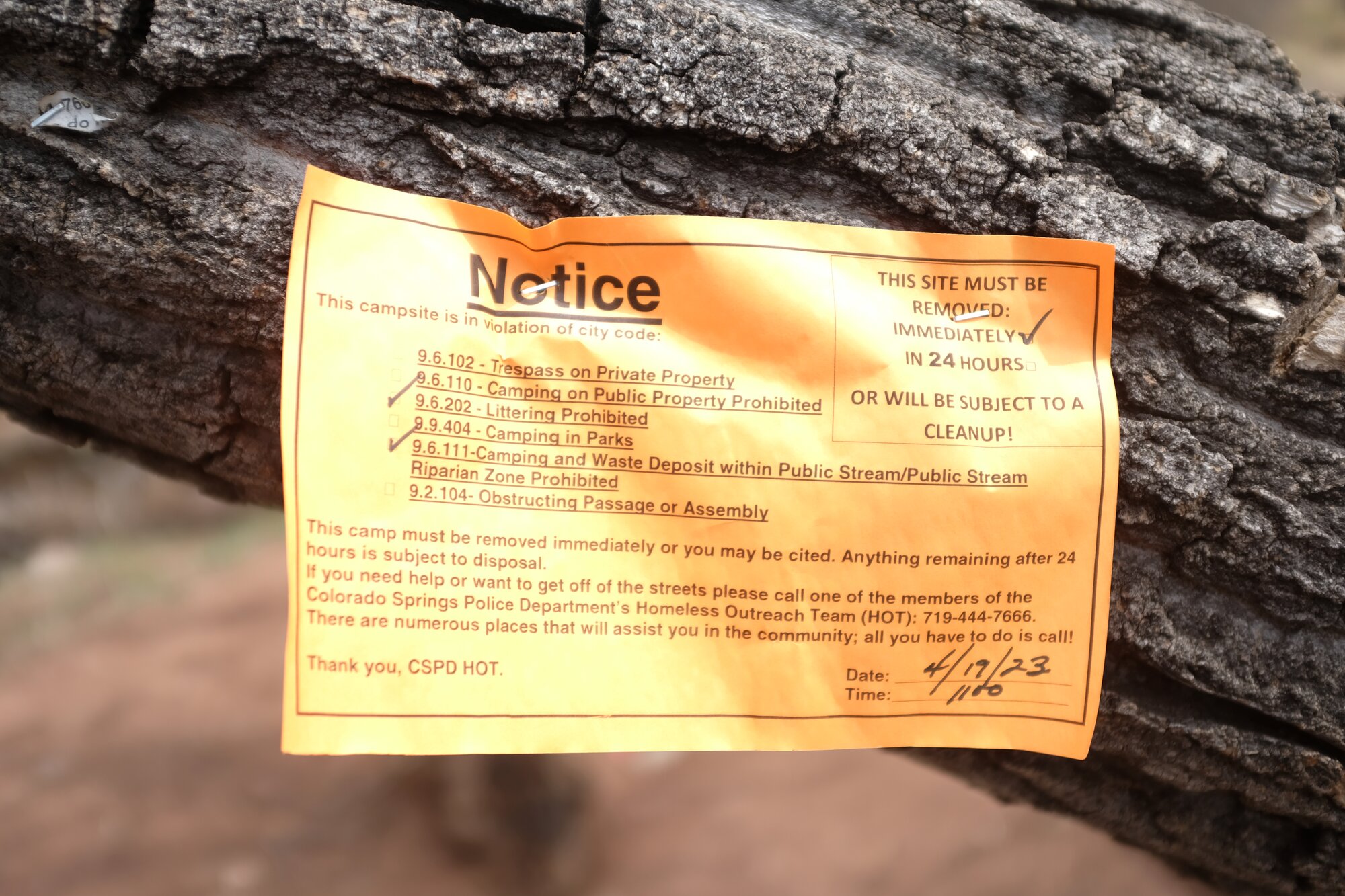

The Homeless Outreach Team, a specific unit within the Colorado Springs Police Department, typically issues a warning for urban camping in the form of an orange ticket outlining specific offenses. “This camp must be removed immediately or you may be cited,” the ticket states.

But Goldsbury and Shepard said they received no such ticket, just the verbal warning followed by their belongings missing hours later. A spokesperson for the Colorado Springs Police Department said they “believed officers swept the area,” on the April 20 morning. Rocky Mountain PBS also confirmed the event with five other unhoused individuals in the area and documented a ticket stapled to a tree at a nearby campsite the same day.

“Everything they took was quite essential,” Goldsbury said. “We just came back and found it gone.”

Hidden underneath the pile of bedding, Shepard kept his stash of small, fluorite rocks. The rocks kept him grounded in an otherwise loud and scary world. Officers taking his rock stash was just as hard for Shepard, if not more so, than the sleeping and shelter supplies.

“They keep taking all my stuff and then I have to start all over again,” Shepard said in an interview, just hours after his belongings were gone.

In his nearly 11 years of homelessness, Shepard has found ways to keep himself busy. He prefers solitude and small company to socializing, which some other unsheltered folks gravitate toward.

Lucky for Shepard, rocks are plentiful around the area.

Shepard designs rock paths all over the West Side, with rocks lined up single file, streaming down grassy patches alongside backyard fences and strips of cracked sidewalk. The paths look intentionally designed, and those who know the area well say Shepard is so well-known for the work, he’s earned the nickname “the rock guy.”

“I pay attention to the ground and just grab the ones I see and like,” Shepard said. “It’s the only thing I can do since they made it illegal to camp in the city.”

The legal cycle

As Goldsbury walks into Judge Edward Colt’s courtroom at the Colorado Springs Municipal Courthouse, a singular thought races through her mind: “avoid jail time.”

Goldsbury appeared in front of Colt April 17 for an arraignment on a “camping on public property,” citation. The offense carries a possibility for jail time, fines and probation. Goldsbury can handle any other consequence, she said, but jail time would mean separating from Shepard for longer than the two already have with previous jail trips, and she worries what he would do without her.

In municipal court, most defendants are attending for misdemeanor violations of the city code. Theft, drug possession and animal control citations all appear in front of Colt before Goldsbury’s name is called. As Goldsbury sits on a wooden bench on the far-left corner of the courtroom, a friend sitting one row away turns her head to give Goldsbury a hug.

“Don’t worry,” the friend says.

“This one’s nice,” she reassures Goldsbury of the judge.

The friend is also unhoused and appearing for a camping ban violation. The two whisper for several minutes before a neighbor hushes them. Goldsbury said this is common: seeing other unhoused people in court for the same reason. She and the friend roll their eyes at the woman who silenced them.

Someone's cranky, the friend mouths.

When her turn is called, Goldsbury enters a “not guilty,” plea and requests a meeting with the city attorney, which the judge grants.

Goldsbury remembers being cited for three camping violations prior to her April 17 court date, but court clerks said only one violation appeared in their system.

“You may get lucky with just the one,” a clerk whispers to Goldsbury after searching for two other citations without luck, cracking a half smile.

“I’d rather just be honest and own up to all three,” Goldsbury responds.

Staying in high spirits

Goldsbury retains her chipper attitude despite legal troubles, having her belongings stolen and dealing with frequent drama. When strangers approach, she greets them with a smile and offers a hug at the end of the meeting. Most of her attitude, she said, comes naturally. But she has also been using meth for 27 years, she said.

“It’s no big deal at this point,” she said. “I don’t change. Not at all. I just go get a little bit peppier and go get stuff done.”

Goldsbury’s dealer lives inside and chats with Goldsbury before handing over $2 worth of meth, just enough.

“It’s not necessarily a business between him and I,” she said of her dealer. “I go, I brighten him up and I hand him a couple bucks to help pay his bills.”

Goldsbury knows meth is incredibly addictive and dangerous; she doesn’t deny what decades of research have made clear.

“A lot of people can’t handle it out here,” she said of others who use the drug. She uses the substance to help her stay awake late at night, a necessary precaution for most people living outdoors, to avoid being attacked or having belongings stolen.

Milligan, the Westside Cares CEO, said using amphetamines to stay up at night and protect resources is common among the unhoused community.

“The reason for that is because they have all their worldly possessions with them at any time, and their safety is most likely to be violated at night,” Milligan said. “A lot of people begin using amphetamines to stay up all night and protect their belongings.”

A little patch of home

Goldsbury stayed in The Salvation Army RJ Montgomery Center — a homeless shelter southeast of her West Side camp spot — for sporadic periods of time before swearing off shelters.

People screaming in agonizing night terrors through the night, fluorescent lights, concrete walls, gated areas feeling eerily like jail, a crowded space with no privacy. It all felt like too much. The exchange of a warm bed hardly made up for the losses that come with staying in a shelter.

Once Goldsbury met Shepard and he made it clear his mental health issues would prevent him from enjoying a shelter, the two committed to sleeping under the stars each night, grasping onto each other, both for warmth and a sense of company.

“They would separate us and I’m his person,” she said. “So that can’t happen and we stay out here.”

Though their belongings were removed and Goldsbury faces several citations for camping, the two plan to stay as long as they can. They’ll consider moving if they’re forcibly removed or find permanent housing.

The couple also feels lucky for their spot along the dirt path, which they call “the forest.” Though it’s small and doesn’t compare to Colorado’s stretches of world-famous public forests, it’s enchanting to Goldsbury.

“We keep it nice here because it is nice,” Goldsbury said. “It’s our forest.”

While many unhoused people cram inside shelters or pitch tents along concrete sidewalks, Goldsbury and Shepard get to fall asleep under a star-lit sky, in the shadow of Pikes Peak, surrounded by shady trees.

Goldsbury knows it isn’t ideal, but while she lays her head next to the man she loves and the two rest alongside the calming swish of creek water hitting rock beds, she’s thankful for her life.

For Amy, that’s more than enough.

Alison Berg is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alisonberg@rmpbs.org.