Unhoused friends and family members describe life together in Colorado Springs

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — JoJo and Karla never imagined they’d spend the majority of their days holding cardboard signs while asking for money outside a small shopping plaza on Colorado Springs’ west side.

The two sit side-by-side behind an electrical box next to a Starbucks between Pikes Peak Avenue and Colorado Avenue. They take turns flying signs around the area. If they’re lucky, they can pool the dollars donated from drivers passing by and coffee shop customers to get a cheap meal from the nearby Taco Bell or Wendy’s.

Karla Chris and JoJo — who did not give her last name — have been friends for nearly 10 years. They both ended up homeless in 2017. The two choose to stay on the West Side for its views of the Front Range foothills, they say.

In 2010, JoJo said, she was driving from Pennsylvania to California to see her brother, with plans to stay in California permanently. While stopped in Colorado Springs, she got sick. Then her car got stolen, making it impossible to leave a city she knew nothing about. She moved from Philadelphia – a city nearly three times the size of Colorado Springs – and said the quietness of her new home was even scary at first.

“It’s so quiet out here, and there’s open space,” JoJo said. “I couldn’t sleep for weeks when I got here.”

Chris and JoJo are like twins: they share everything. They even share a birthday, March 13. They’re both Pisces, which they note as a core facet of their personalities.

And, in typical sibling fashion, the two frequently find themselves bickering, usually over something small and forgotten minutes later.

“Why do you keep talking over me?” Chris asked JoJo during the interview. “I’m gonna walk away,” she added.

“I’m sorry. I love you,” JoJo responded, cracking a half smile and throwing her arm around Chris.

The two said living outside brings a revolving door of struggles: don’t sleep too long or someone will steal your belongings. Don’t camp too publicly or the police will find you. Don’t make the wrong person feel threatened or you could end up injured or dead.

In her six years living outside, JoJo said the landscape has changed: you used to know every unhoused person on your side of town. Now, she said, new tents seem to be popping up all the time, and she often fears who’s inside.

“Now there’s an influx of people from all over, of all ages, and you never know what you’re going to get,” JoJo said. “Some of them are very disturbed and they need lots of mental help.”

JoJo and Chris said they take pride in avoiding illegal substances, which is unusual for many unhoused folks. But living outside has turned them both into alcoholics, they admit.

“There’s no rest out here on the streets,” JoJo said, taking a swig from a small bottle of Burnett’s vodka. “They’ll steal everything you’ve got.”

“They,” means one of two groups: either another unhoused person or the Colorado Springs Police Department Homeless Outreach Team.

“Nobody else is interested,” JoJo clarified about used sleeping bags, dirty tarps and ripped-up pillows. To those with more privilege, such items are litter in parks. To the police, they’re evidence of the misdemeanor crime of camping within city limits. To other homeless people, they’re essential tools for survival.

“It’s brutal out here,” Chris said. “The police will laugh at you.”

Most folks in houses — or “insiders,” as many unhoused people call them — leave JoJo and Chris alone, going so far as to avoid eye contact or even acknowledge their presence. Some will pass on a smile; some will even drop some spare change. But some, the two said, can be cruel enough to ruin a day.

“Last week, I had a guy roll down the window and tell me to get a job,” Chris said. “I told him I have a job, dealing with a--s like him.”

JoJo and Chris know everything about each other’s lives: their families, mental health struggles, romantic relationships, and conflicts with other people experiencing homelessness. Though sleeping outside and dealing with the harsh realities that come with it is painful, doing so with your best friend makes things easier, they said.

“If you can’t laugh about it, you’ll never make it out here,” JoJo said, taking another swig from the Burnett’s bottle.

A mother and son

Gina Koch was ecstatic when her son, Josh, and his daughter — her only grandchild — arrived in Colorado Springs from Wisconsin seven years ago. She came to town three years earlier with her husband, leaving nearly all of their belongings behind.

The two had a friend in town who helped them get on their feet, but eventually struggled to pay rent on their own. Once Koch’s husband needed surgery and could not keep working through the COVID-19 pandemic, she resorted to living in her car, the only option in a sea of skyrocketing rents.

“It’s horrible,” Koch said.

On a cloudy, cold morning April 20, Josh and Gina sat next to a green steel picnic table at Vermijo Park, a park next to Fountain Creek on the west side of Colorado Springs.

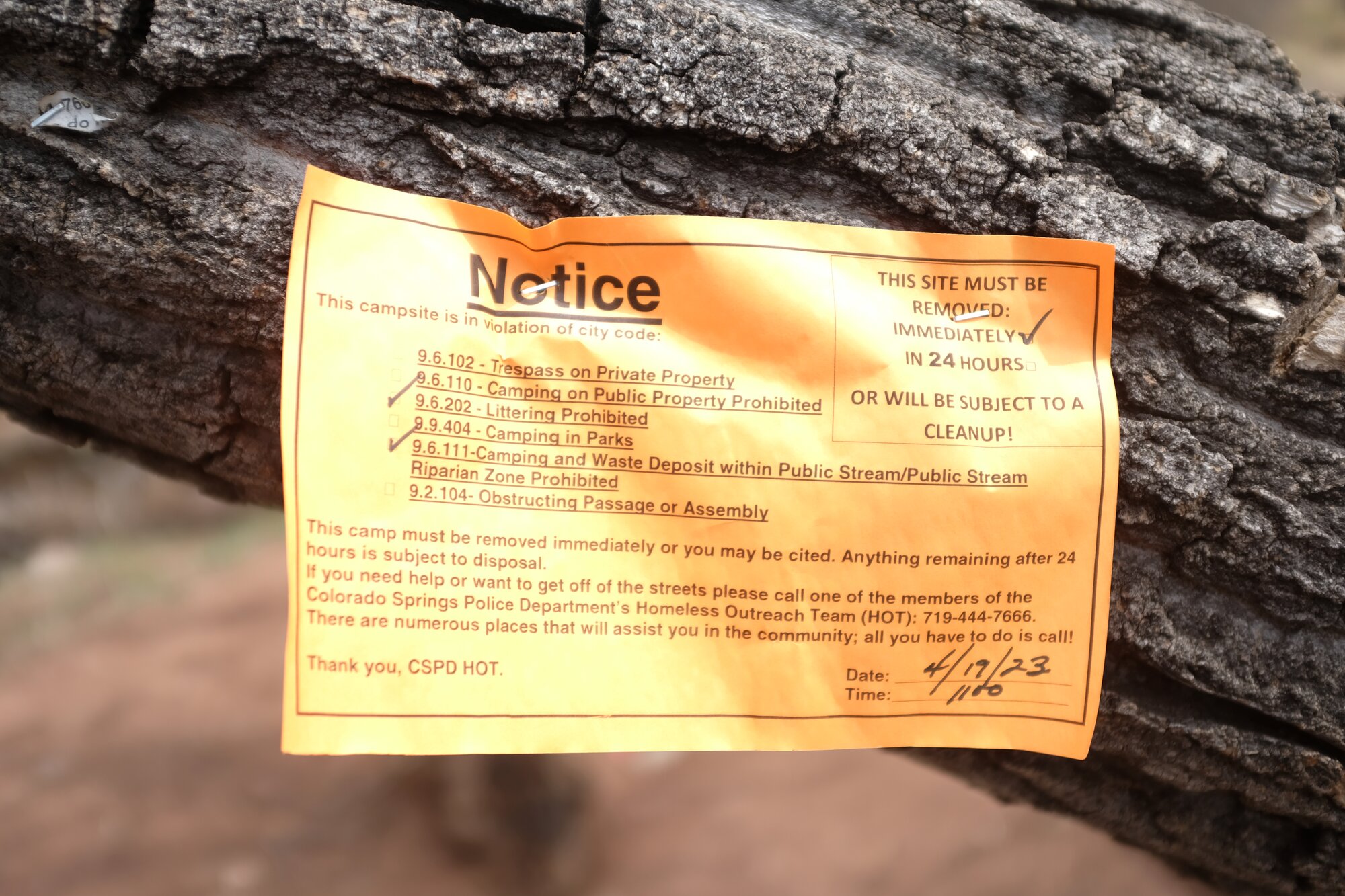

The Koch’s were surrounded by other people experiencing homelessness who were shooting hoops, passing cigarettes around and commiserating a sweep from the Homeless Outreach Team earlier that day. Police officers on the team normally attach an orange tag that states, “This camp must be removed immediately, or you may be cited,” to campsites breaking the city’s urban camping ban. Once the tag is attached, campers have 24 hours to move their belongings before officers issue a citation.

Though the 24-hour rule is Colorado Springs’ standard, the Kochs and others at the park said officers took their belongings without warning that morning.

“Cops are not friendly here to people who don’t have a home,” Josh said. “Because you’re homeless, you’re worthless to everybody in society.”

Josh has epilepsy and receives monthly disability payments of $900 since he cannot work. Still, $900 is hardly enough to live on, he said, particularly as Colorado Springs continues to see increasing rents with little relief.

“I can’t live here,” Josh said.

Josh also has a pacemaker in his chest and wears a magnetic watch on his left wrist. If he starts having a seizure, he can wave the band in front of the pacemaker and the seizure stops. Sleeping outside is far from ideal, Josh said, but staying in a shelter, risking a seizure and dealing with people who don’t know how to help and could potentially exacerbate the problem would be far worse, he added.

“If I go to a shelter and it has the wrong lights in the ceiling and I end up having a stroke, what’s worth more, taking a chance at getting a fine (for urban camping) or dying,” Josh said. “I could go to a shelter at night but that could turn into an emergency for me.”

Gina now sleeps in the back of a truck that her husband’s boss lets the couple stay in, and Josh camped outside for his remaining days in Colorado Springs.

But after years of dealing with theft, violence and police brutality, Josh left Colorado Springs for a cross-country hike to Iowa, where he plans to live with a friend for a bit before living on a boat on the Mississippi River.

The morning before he was slated to embark on the hike, Josh packed his dark green backpack with all his belongings: rope, dehydrated eggs, a camp stove, binoculars, a battery pack and 12 pounds of dog food for his dog, Bolt. The backpack totaled about 80 pounds but wasn’t too heavy for Josh.

“The situation here is bogus,” Josh said of mistreatment from police and others. “It is corrupt, and it is against the people.”

“I’m worth less than a dog to the city here,” he added.

Gina plans to stay in town, living in the back of the truck. She said not seeing Josh every day will be heartbreaking, and she’s requiring him to send a daily photo or video from the hike. Having a friend or close family member is essential to surviving life outside, Gina added.

“I think it makes it easier when you have somebody with you out here,” Gina said of experiencing homelessness alongside her son. “I think you need to have somebody.”

Progressing through the system

Kat and Mouse feel fate brought them together.

Mickey “Mouse” Hood and Kathleen “Kat” Misze consider themselves partners in progress through vocational programs at Springs Rescue Mission, Colorado Springs’ largest homeless shelter, located just south of the downtown corridor.

“We’ve already decided we’re stuck together even when we make it out of here,” Kat said, turning to Mouse. “Sorry, you’re stuck with me forever,” she added as Mouse chuckled and grabbed her hand.

The two met in a class at Springs Rescue Mission and vowed to do all they could to absorb the material and apply it as quickly as possible. Soon, they hoped, they could be on track to more independent lives. Mouse works in the kitchen at the shelter and Kat does laundry.

Both are enrolled in the “Passport to Hope” program, which teaches residents vocational skills using Christian-based principles. The two women said they’ve enjoyed the program because it’s helped them see hope for their futures via stable housing.

“Me being here kind of opened my eyes to things and situations that I didn’t know how to do -- and I do now,” Mouse said. “It’s really awesome to have something you feel you can grasp onto.”

Mouse fell into homelessness when her mother-in-law sold the condominium she and her husband were living in. Kat left her home state of Michigan for better job prospects in Colorado but soon fell victim to wages not covering living costs.

“Once I’m out of here, I’m looking for a position answering phones and answering questions on the phone,” Kat said. And like many seeking solace from and on the streets, "Having a friend in here, I’m a lot easier on myself,” Kat said.

Alison Berg is a reporter for Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alisonberg@rmpbs.org.