First Creek renovations to bring back what was lost and adapt to a new age

share

This article is part of reporting for an episode of season of 11 of Colorado Experience set to premiere this fall on Rocky Mountain PBS.

COMMERCE CITY, Colo. — Parking in a dirt lot near East 56th Avenue and Peña Boulevard in north Denver, Scott and Stacie Gilmore walk a short route along a road to look upon the vast Colorado prairie.

It’s a stark difference to the path Scott Gilmore used to take out here 40 years ago.

“As a teenager, I would actually drive over to the [Rocky Mountain Arsenal] and sneak through the barbed-wire fence and see the eagles before the majority of people knew that there were bald eagles there,” Gilmore said.

In the late 70s when Gilmore was a teenager, the National Wildlife Refuge did not yet exist. Production of pesticides by the Shell Oil company was winding down but the 17,000 acre Rocky Mountain Arsenal belonged to the U.S. Army and was closed off to the public.

Now, 45 years later on this same stretch of land, there are trails and a dedicated road off 56th that the Gilmores use and serves as a community access point for Montbello and Green Valley Ranch residents into the Refuge. Without this point, neighbors would need to trek to the Refuge’s main entrance east of Quebec Parkway in Commerce City.

Despite the leap in accessibility to the wildlands of the Refuge, the First Creek Trail is currently closed due to regular flooding as a result of increasing urbanization and work done to narrow the creek about 100 years ago.

“It's just so continual year after year that these communities and these roads are being flooded, closed and everything else because this water is passing through us too quickly,” said David Lucas, the Refuge project manager.

But, now, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife is heading a project to repair the First Creek Trail and restore its route throughout the Refuge.

“You can't just re-naturalize [First Creek] to its historic conditions because that train has left the station,” said Dave Skuodas, the design, construction and maintenance director with Mile High Flood District, which looks at urban waterways in the Denver Metro Area and how they’re managed.

“So, the watershed is different now. We end up using a design approach that is a blend of trying to mimic natural form and processes with completely unnatural watershed conditions,” Skuodas said.

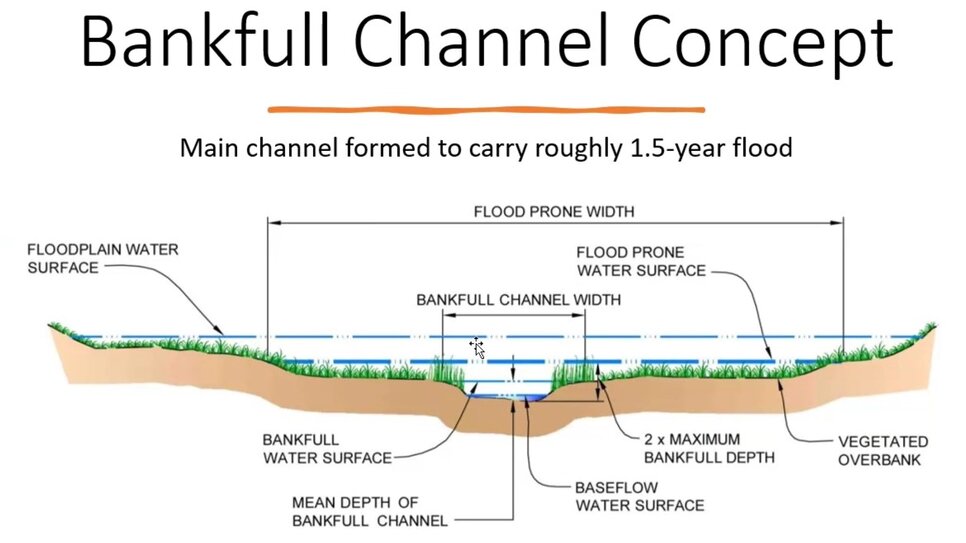

Illustration provided by U.S. Fish & Wildlife demonstrates how widening the creek to create more flood prone width will allow for more water to fill up First Creek and its riparian zone at the Refuge without flooding streets and other parts of the creek downstream.

The two-and-a-half year project aims to return First Creek to a more natural state and prevent future flooding — not only of the trail but also the roads and communities surrounding the Refuge.

Though boots-on-the-ground work began in March of this year, David Lucas, the Refuge project manager, said restoring the creek has been 30 years in the making.

“1994 was the first conceptual plan that was produced,” Lucas said.

But funding the project at that time became difficult with funds going to establish the wildlife refuge.

“It was reinvigorated when we updated the master plan for the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in 2016.”

The full story of First Creek, which courses through 5.3 miles in the Arsenal, doesn’t begin there. As a tributary of the South Platte River, First Creek contributes to a major waterway that’s been around thousands of years with American Indian tribes traveling and living in the area where the South Platte and Cherry Creek Rivers converged.

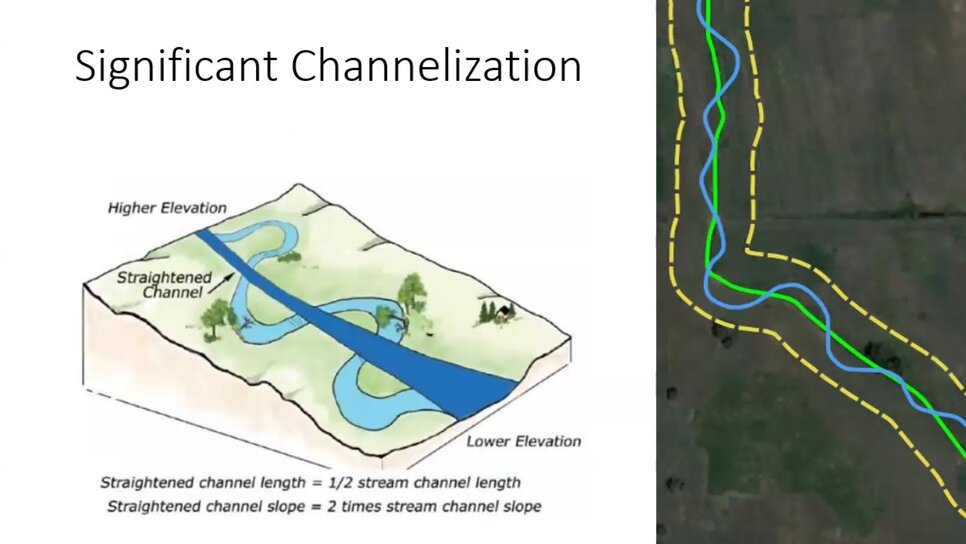

In the early 1900s homesteaders channelized First Creek by making it straighter and narrower allowing for easier irrigation for their farmland.

Illustration provided by U.S. Fish & Wildlife shows how adding curvature will change the land at Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge.

The U.S. Army then made other changes to the creek and surrounding wetlands when it used Arsenal property for chemical weapons manufacturing in the 1940s — the weapons produced at the arsenal were never used.

Over time, further development of Denver and surrounding suburbs brought more changes to the watershed. The hard surfaces of roofs, buildings and concrete roads — rather than porous prairie land — added more runoff into the few remaining waterways, including First Creek.

On top of that, Lucas said Colorado’s climate change patterns result in quick rushes of water into streams and rivers followed by dry spells.

All of this means First Creek is prone to flooding and cycles of dryness that it never experienced prior to urbanization.

First Creek in the Green Valley Ranch Neighborhood showing natural curvature and revitalized nature.

Photo: Amanda Horvath, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Amanda Horvath, Rocky Mountain PBS

“We'll build infrastructure that ends up looking like nature. And this is just kind of an extreme example of that, as it is very much infrastructure, and it is a very engineered, intentional design,” said Skuodas. The design Mile High Flood District provided includes widening and adding curvature to the creek.

“But once it's built off, all done the right way, and if the design's gotten close enough to something that'll be really sustainable, then a few years from now, after we vegetate, somebody walking by would think, God put it there,” he said.

Widening the creek will slow down the current rates at which water moves through the waterway and lessen the degradation of First Creek, allowing for greater water capacity.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sought the help of Mile High Flood District to design plans for the First Creek renovations last year when funding finally came through in a roundabout way, thanks to buffalo.

In 2023, the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge received around $2.5 million from the Inflation Reduction Act to improve the lives of the about 250 American buffalo that live at the Refuge. The funds accounted for new fencing, expanding the area where the buffalo roam and also improving the waterway the herd uses — First Creek.

“Our concept was these animals will behave better if they're getting water from natural ecosystems,” said Lucas. “The way the water's rushing through here in a channelized fashion isn't natural. There's not ponds, and the animals like to go back to those spots year after year.”

The buffalo — whose scientific name is bison bison — not only benefit from the changes coming to First Creek but Lucas hopes they’ll also help restore the riparian zone around the creek. The riparian zone is the in-between area along a river or creek before expanding out to dry land. The way buffalo graze, their patterns of movement and stamping hooves encourage plant regeneration.

“The bison have done such a great job with all the other habitat restoration, that they'll help us with the riparian restoration over time because this whole world kind of evolved with them,” said Lucas.

In the meantime, the restoration project includes plans to plant 1,500 native trees, shrubs and sedges along the riparian zone of the river. Designers plan for plants that will thrive along river banks and often grow best in flooded areas. Without the width and curvature to allow for healthier floodplains, Lucas said, the cottonwood trees at the Refuge have begun to struggle.

Fallen tree at First Creek just outside the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge.

Photo: Amanda Horvath, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Amanda Horvath, Rocky Mountain PBS

“If everything is just shooting through an eroded channel, [cottonwoods] won't regrow. So the trees are getting older, they're falling over and dying, which means we lose habitat. We lose habitat for eagles, all sorts of other species,” said Lucas.

The bald eagles are incredibly important at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge. Not only are they, of course, America’s national bird but they are also the reason why the former arsenal became a wildlife refuge.

In the 1980s, when the collective consciousness of Americans was generally shifting towards environmentalism, bald eagles, who were then on the endangered species list, were discovered to be nesting on Rocky Mountain Arsenal grounds.

Their survival became the principal reason for the federal government to turn the Superfund site into a national wildlife refuge.

For kids like Gilmore who grew up in the area, spotting one of the eagles was rare and special. For their first date in the early 90s, Gilmore took his wife, Stacie, to the gap in the fence where he used to sneak onto Arsenal property. By then, the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge Act was passed, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife asked for volunteers to go on “eagle watch” and help document the animals, no crawling through barbed-wire required.

The Gilmores, who separately pursued careers in environmentalism and wildlife biology, shared the mission.

When it came time to start a family, the Gilmores looked to the Montbello neighborhood, a traditionally Black and underserved community of Denver that borders the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge to the south.

“When they built this development in this part of Montbello, they did not build one park, not one,” Scott Gilmore said of the city planning.

“They took credit for the parks that are around this development, but they didn't build one park. And that just sends a message that Black and brown people don't deserve green spaces. So we're trying to change that narrative.”

Scott and Stacie Gilmore enjoying a drive along Old Buckley Road. On one side is the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge and on the other side is the First Creek at DEN open space.

Photo: Peter Vo, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Peter Vo, Rocky Mountain PBS

In the mid-90s Scott and Stacie Gilmore co-founded Environmental Learning for Kids, a nonprofit that focuses on giving all kids access to science education and connection to the outdoors.

Now in their respective roles — Scott as the head of Denver Parks and Recreation and Stacie as a Denver City Councilor — they continue to make the environment and equitable access to the outdoors a top priority.

“I see it as an environmental justice movement,” said Scott Gilmore.

“I see it as a piece of equity that we need to engage in to make sure that people that have been marginalized and excluded from high quality parks and green spaces in their communities because it costs money, that they deserve those spaces now,” he said.

Denver Parks and Recreation recently opened the First Creek at DEN open space parallel to the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge at the intersection of East 56th Avenue and Buckley Road.

Photo: Amanda Horvath, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Amanda Horvath, Rocky Mountain PBS

To that end, Scott Gilmore also oversaw the opening of Denver's largest open space on the other side of the First Creek trail called First Creek at DEN.

“Before that, it really wasn't safe to try to access the Refuge from that side because there really wasn't any good access,” said Stacie GIlmore. “It's a great time right now for us to really reintroduce the community to the Refuge and the history around it, since we have better and safer access points to get into it.”

Lucas and his team, who are trained in landscaping, will be doing a lot of the excavation and repair work themselves with big equipment. Keeping the labor in-house will help keep the cost of the project to around $2 million, Lucas said.

Work on First Creek and the trail is expected to be done in the winter of 2026.