Bison conservation efforts ramp up in Colorado

This article is part of ongoing reporting and production for a new episode of Colorado Experience called “Return of the Buffalo”. Part 1 is set to premiere October 12 at 7 p.m. on Rocky Mountain PBS.

COMMERCE CITY, Colo. — On a cool summer morning, quietness settles over the prairie. Only nature is audible. A warm breeze rustles the grass and the meadowlarks' songs are punctuated by the grunts of buffalo, who fit perfectly into this puzzle of prairie life.

“We have to all work together to conserve bison in their native landscape,” said Megan Klosterman, the deputy refuge manager at Rocky Mountain Arsenal Wildlife Refuge.

Bison conservation has received more attention in the last five to 10 years than ever before. On Sept. 7, the Department of the Interior announced $5 million for the “support the restoration of bison populations and grassland ecosystems in Tribal communities.” This investment supports Secretary Order 3410, which was announced in March 2023 and is the larger investment of $25 million from the Inflation Reduction Act to restore bison and prairie ecosystems through Indigenous knowledge of the species.

Klosterman said Rocky Mountain Arsenal, located in Commerce City, is part of a greater initiative to work with Indigenous groups to bring back and protect the buffalo.

Bison once numbered in the range of 70 million across North America prior to Europeans settling on the continent. Then, for a range of reasons but primarily to “settle the West,” which was the excuse made for clearing out the megafauna — the bison — and the American Indians who heavily relied on the buffalo for subsistence, European Americans killed most of the buffalo, which brought the species near extinction and nearly destroyed many American Indian tribes. Over the last 100 years, conservationists and American Indian tribes have worked to bring back this important animal to the ecosystem.

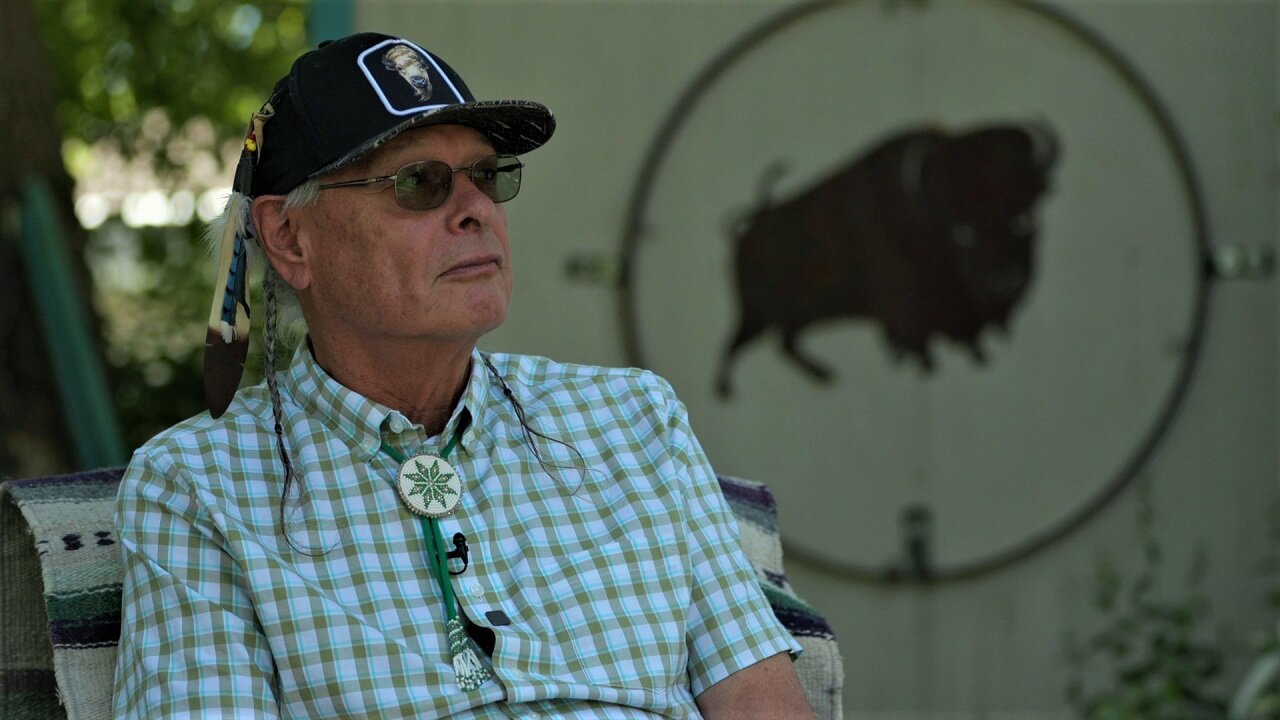

Rick Williams is a community leader and a member of Oglala Lakota and Northern Cheyenne tribes. Photo by Melanie Towler, Rocky Mountain PBS

“People are beginning to understand that we can't control Mother Earth. Mother Earth is going to control us. And so, I think that it's almost imperative that we bring the buffalo back,” said Rick Williams, board president of People of the Sacred Land, an organization that aims to reveal the ways American Indians were mistreated throughout Colorado’s history and create an equitable future for American Indians.

Prairie grasslands stretched for miles across the state as did herds of buffalo who play an important ecological role in the landscape. Colorado is home to nearly 50 different tribes who traversed this land much like the buffalo did.

“It's so important that we believe that the strength of the herds of buffalo who are coming back parallel our existence, we will never be strong as a people again until we have the buffalo back,” said Williams, who is Oglala Lakota and Northern Cheyenne.

Buffalo are incredibly intertwined with many Indigenous Tribes and Nations, especially the Lakota, Williams said, and not just as a source of food, tools and clothing.

“Part of that relationship is a spiritual relationship, the spirit of that buffalo and my spirit can interact with each other and understand each other,” said Williams.

In the 1990s, Williams was part of a group that created what is now the InterTribal Buffalo Council. ITBC is a collection of more than 80 tribes across the country who manage more than 20,000 buffalo. The organization is benefiting from the new federal funding, using the money to help educate and fund the animals’ care.

The Southern Ute Tribe in Colorado is one of the founding tribes of ITBC. Their herd was established in 1984 with just eight bison and has grown to 115 bison. This size of the herd sustains their meat program, which provides five pounds of free bison meat each month to all 1,500 tribal members.

[Related: Southern Ute Tribe’s bison herd at maximum capacity due to environmental restrictions]

One of the main reasons [to return buffalo to tribal lands] is to help restore our food sovereignty and our traditional food system,” said Stacey Oberly, a Southern Ute Tribal council member and representative for the tribe with ITBC.

The other reason to return the bison to prairie grasslands is the incredible ecological role the animals play — an aspect Oberly, Williams and Klosterman all talked about extensively.

Bison play an important role in the prairie ecosystem, like this land at Rocky Mountain Arsenal Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Julio Sandoval, Rocky Mountain PBS.

“That symbiotic relationship that we had with the buffalo also goes all across the environment. The prairie dogs love the buffalo, the grass loves the buffalo, explained Williams. “Even the bugs and mosquitoes like buffalo.”

As the World Wildlife Organization explains, bison graze grasses at different heights which not only replenishes the grasses but also provides nesting grounds for birds. Buffalo also roll around as a way to shed their coats and rid themselves of bugs. That rolling creates depressions in the ground called wallows. Those wallows then fill with rainwater and become sources of drinking water for wildlife across the plains. The wallows are also home to several medicinal and rare plants that rely on these spaces to grow.

“[Buffalo] fiber is the second warmest fiber in America. And so, when animals use that fiber to line their nests, the animals that nest on the ground, the scent of the buffalo masks the scent of their babies in their nests. So, the predators can't send them to find their babies,” explained Oberly.

Buffalo hooves also churn the soil and create microclimates for new plants to grow. And bison use their big heads and shoulders to plow through the snow to eat the grass in the winter. This plowing activity benefits other animals like pronghorn antelope and elk.

"Bison were selected to be part of this refuge because bison are a keystone species in the prairie ecosystem,” explained Klosterman.

At Rocky Mountain Arsenal Wildlife Refuge, more than 200 bison live on 6,300 acres of land. Visitors to the refuge can see the bison for themselves using an 11-mile wildlife drive. The refuge also boasts 20 miles of hiking trails and many other animal species.

“We are really hoping that we are a place where people in the urban communities here can come experience wildlife in nature and really find their place in this natural environment,” said Klosterman.

The refuge donates new bison to Tribes or other conservation herds hoping to bolster their own herds. The bison’s area at the refuge will soon expand to 11,500 acres, giving the animals even more space to roam, which Williams said is something they desperately need to thrive.

“They'll come back if they're treated well and they can have that freedom again, not being confined, not being unable to roam and be buffalo,” said Williams.

Bison herds are a matriarchal society and follow the lead of the female bison. Photo by Julio Sandoval, Rocky Mountain PBS.

While the refuge is a good place to conserve bison, Williams is talking about bringing back bison as true wild animals. In fact, he believes we, as a country, should create corridors for buffalo to move freely north and south as they did for thousands of years.

“They need more land. And that is the critical issue that we're facing. We've seen a diminishment of buffalo grass and grasslands that would be suitable for buffalo going away,” said Williams.

While this idea may seem radical to some, Williams believes returning the buffalo in this way will not only help the grasslands, the environment and Indigenous ways of life but restore some balance that has been missing in this area for the last 150 years.

“My message to all people — because it's going to take more than just the Indians to do this — if you really want to make a difference in the world, find a way to bring buffalo back,” said Williams. “If you want to make a difference in this world, bring buffalo back.”

Amanda Horvath is the managing producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at amandahorvath@rmpbs.org