How to save a synagogue

TRINIDAD, Colo. — Once again, public media saves the day.

In the fall of 2016, Littleton-resident Neal Paul was listening to a Colorado Public Radio story on Temple Aaron, a Trinidad synagogue that was preparing to close its doors for the first time in 127 years.

Paul, a Jewish man born in Israel and whose parents survived the Holocaust, decided to visit the temple in person to “see what it was all about.”

This was Paul’s first time in the city of Trinidad, much less Temple Aaron. Yet one tour later, he was convinced.

“It just hit me,” said Paul. “This building needs to be saved.”

Paul, the sitting president of Temple Aaron, is one of many from around the country who have united to save Colorado’s oldest continuously operating synagogue in the name of community and cultural preservation.

Temple Aaron was built in 1889, a time when the Jewish population in Trinidad was much more robust than it is today.

At the time Temple Aaron was built, Trinidad welcomed residents from varying cultural and ethnic backgrounds thanks in part to its location along the Santa Fe railway.

“Between Chicago and Los Angeles, Raton Pass was the highest point for the rail,” said Paul. “Trinidad was the last stop before the train went over the Raton Pass, so Trinidad became a stop on the train line."

The city also boasted a booming coal-mining industry and a strong agricultural market as well, drawing many immigrants to the mines and fields.

Among those moving to Trinidad were German-Jewish settlers, often migrating west from the East Coast. The city’s Jewish population may have at one time reached as high as 300, according to Paul, as Jewish miners, merchants and civic leaders moved to Trinidad.

Sam Jaffa, Trinidad’s first mayor, was Jewish.

Jaffa also played an integral role in the founding and construction of Temple Aaron. He and his brother, Sol, named Congregation Aaron for their father, who had been a Rabbi.

This congregation is referred to as a minyan, or the quorum of Jewish adults (usually ten) required for communal worship.

With support from the Jaffas, Temple Aaron was built six years later; a plaque on the front wall of the synagogue still reads “Temple Aaron Founded 1883," in honor of when the minyan first met.

Temple Aaron’s first minyan met at Sam Jaffa’s house in 1883, according to Paul.

Photo: Chase McCleary, Rocky Mountain PBS

The building was designed by Isaac Rapp, a renowned architect who designed a number of other significant landmarks across the Southwestern United States. Today he is credited as one of the founders of the “Santa Fe style.”

Gradually, Trinidad’s Jewish population declined as many Jewish residents moved to larger cities, according to CPR News. More recent economic challenges, including the 2008 financial crisis, further strained the funding and the population of both the city and the synagogue.

Finally, in 2016, the then-leaders of Temple Aaron — Ron and Randy Rubin — decided it was time to sell.

Devon McFarland can still remember first seeing the “For Sale” sign.

“I was flabbergasted,” said McFarland. “And then I started hearing rumors that there were people trying to figure out what to do with it: should we make it a coffee shop? Should we make it a brew pub.”

“It was a travesty.”

McFarland moved to Trinidad with her family in 1991. She set up a law practice and became an actively engaged resident, stepping forward and speaking out on gambling proposals and coverage of Trinidad’s history.

McFarland is also a member of the Catholic Church and has long served as a cantor. However, when it comes to Temple Aaron, McFarland believes the significance of the building stretches beyond religion.

“This is a small community, and it’s all our culture,” said McFarland. “Whether you’re Muslim, whether you’re Jewish, whether you’re Catholic… so we kind of all are in each other’s consciousness.”

McFarland’s voice teacher, a Catholic woman who she used to cantor with at her church, often sang for the High Holy Days at Temple Aaron.

“I never forgot that,” said McFarland.

Paul shows off a Temple Aaron postcard, one of the many he and others have used to help promote the historic landmark.

Photo: Chase McCleary, Rocky Mountain PBS

McFarland is one of many who were inspired to support Paul and others to prevent Temple Aaron from becoming an office building or a yoga studio (two other considerations at the time).

Word of the synagogue’s sale spread across rapidly. Print pieces published in the Denver Post and on-air coverage across Colorado Public Radio alerting audiences not only in Colorado, but across the country.

Messages of strength and support, sometimes sent with monetary donations, began reaching the Temple Aaron. By 2017, outcries of support and a gradually growing donation pool convinced the Rubins to take the synagogue off the market and pursue a permanent endowment.

Paul remembered calling on friends and colleagues to pitch in to save the synagogue. His background in real estate and construction both came in handy, and still today, Paul takes bi-monthly trips from his home in Littleton down to Trinidad to work on minor repairs and upkeep.

However, much of the Temple’s needs are well beyond the abilities of a single DIY-er.

“We have original stained glass windows in here,” said Paul. “The roof on this building is original. It’s almost a little miracle that the roof itself still stands.”

When Paul first began working on the temple, he found that the boiler — which dated back to the 1970s — had long since failed. It required nearly two years of determined fundraising to replace it.

This helped restart in-person events taking place in Temple Aaron, most of which are High Holiday celebrations such as Rosh Hashannah, Passover and Yom Kippur. While services have also been restored, many take place online and welcome attendees joining from computers across the country.

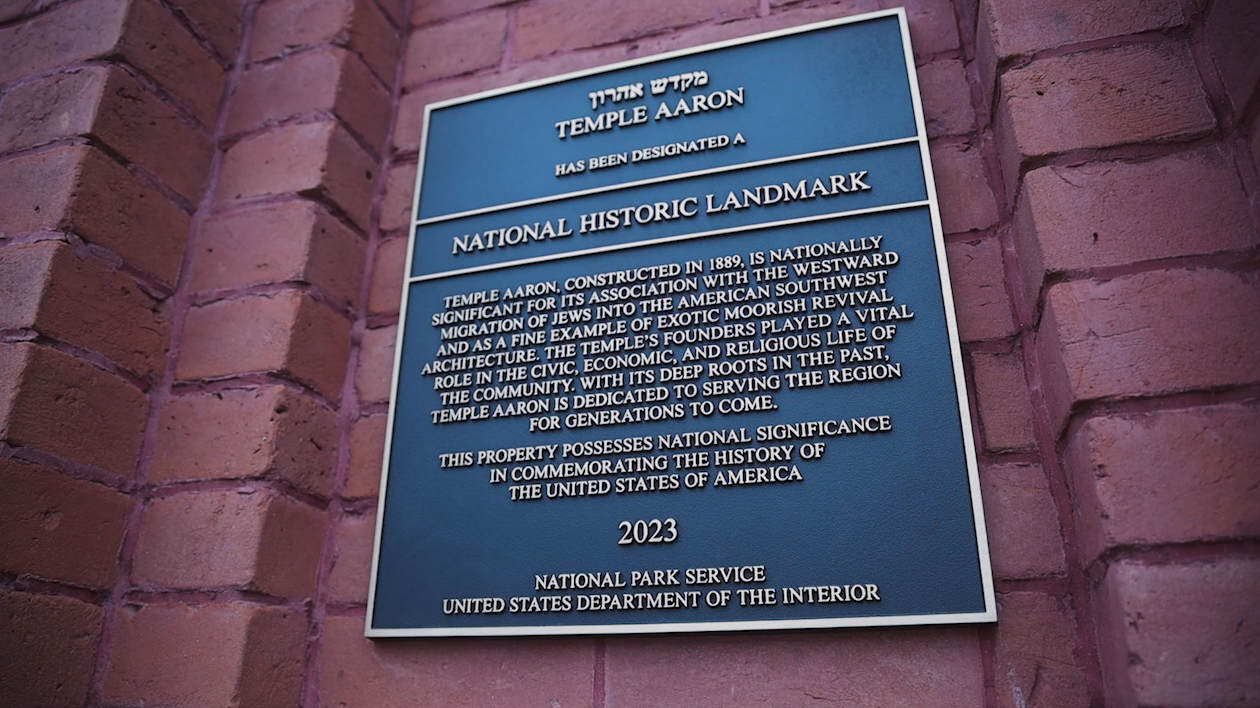

In December 2023, Temple Aaron received National Historic Landmark status, a four-year long endeavor made possible by the growing attendance, support and community efforts behind the synagogue.

As a National Historic Landmark, Temple Aaron is eligible for certain federal funding and tax breaks, along with being recognized as a historically significant location.

Photo: Chase McCleary, Rocky Mountain PBS

This designation made Temple Aaron only the 27th National Historic Landmark in the state — there are more than 1500 listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Paul hopes that this status will allow Temple Aaron to apply for federal funding and also further publicize one of Trinidad’s most iconic historic landmarks.

He also hopes that it may inspire someone local to Trinidad to take over his role as key-master to the temple.

“My goal, hopefully in the not too distant future, is to be able to hand these keys back over to the community, to the Jewish community of Trinidad,” said Paul.

“This building does not belong to me. It does not belong to any one people. It belongs to the community that it was built for.”

Chase McCleary is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS. Chasemccleary@rmpbs.org