Denver Pride turns 50 this weekend. Here’s how it changed through the decades.

share

LGBTQ+ people and their allies march to Civic Center Park at a Pride festival in the 1990s.

Photo courtesy History Colorado.

Photo courtesy History Colorado.

DENVER — Each year, around 500,000 people — nearly two-thirds the population of Denver — flock to Civic Center Park with rainbow face paint and flags of all sorts to celebrate Denver PrideFest.

Held on the third weekend of June, Pride weekend boasts a parade from Cheesman Park to Civic Center, parties, bars and restaurants offering rainbow-themed food and drinks, and local shops decorating their windows with rainbows and messages of support for the LGBTQ+ community.

2024 marks 50 years of Denver’s Pride celebration, and LGBTQ+ historians in Denver believe Pride’s modern celebrations should also include discussions of its rebellious, rag-tag history.

“It was the beginning of a cultural phenomenon,” said David Duffield, history coordinator for the Center on Colfax, the largest LGBTQ+ resource center in Denver whose staff plan and host Pride. “But before it was what it is today, it was a protest.”

The country’s first documented Prides began one year after the Stonewall Riots, which took place June 28, 1969. The Stonewall Inn — a bar in New York City owned and operated by the mafia — was a frequent, discrete and unofficial gathering space for LGBTQ+ people. Police raided the bar about once a month throughout the 1960s, arresting and harassing its patrons for “cross-dressing” and open displays of affection towards those of the same sex, including dancing and hugging.

On June 28, as police used force to haul employees and patrons out of the bar, LGBTQ+ activists around Greenwich Village united to fight back, throwing objects and using physical force to resist arrest and counter the police.

The following year, protests in San Francisco, Chicago, Los Angeles and New York City commemorated Stonewall and increased visibility for LGBTQ+ people.

In 1972, five LGBTQ+ Denverites brought the movement to Colorado. Gerald “Jerry” Gerash, Lynn Tamlin, Jane Dundee, Terry Mangan and Mary Sassatelli formed Colorado’s first documented LGBTQ+ political activist group: the Gay Coalition of Denver.

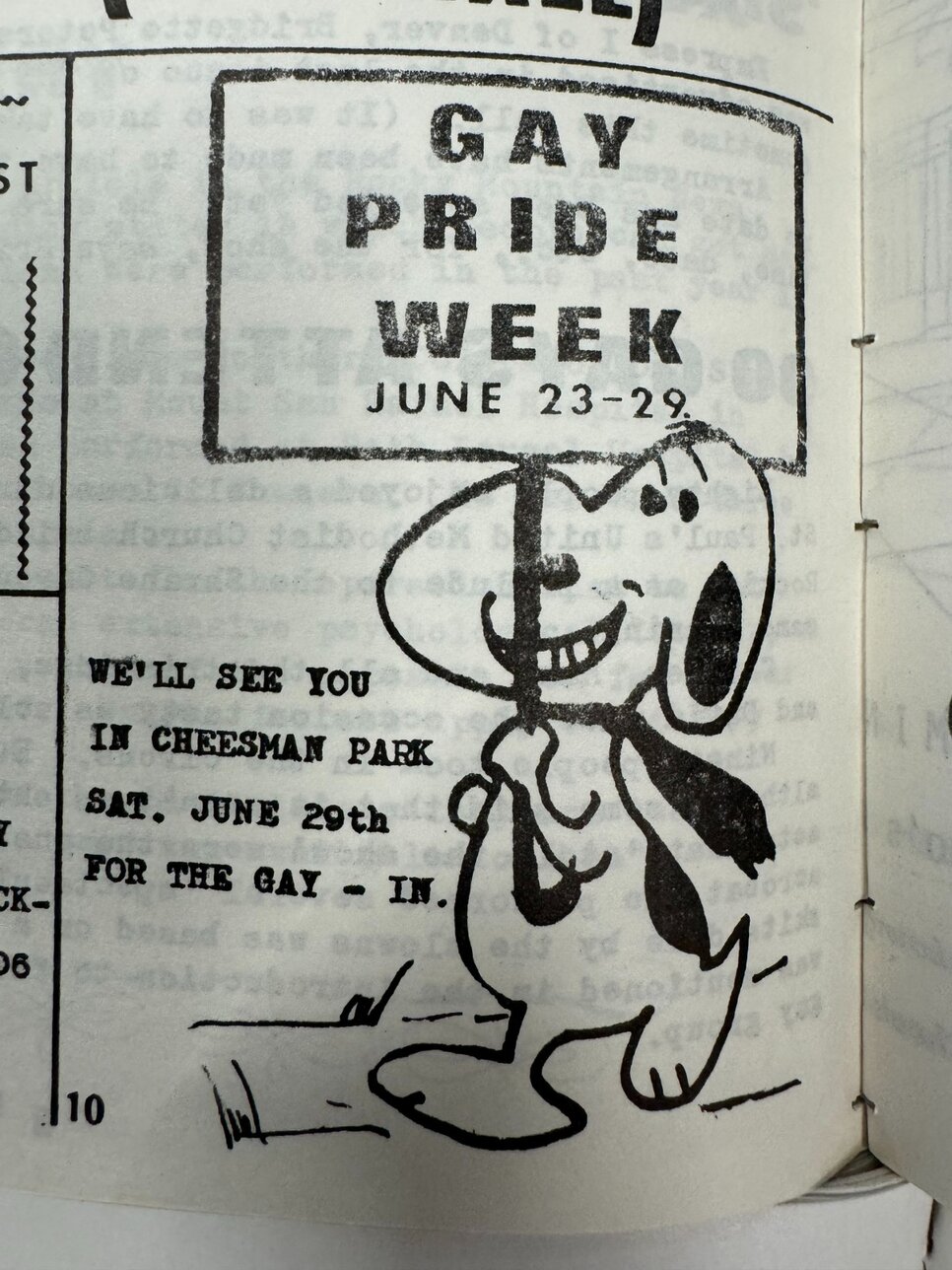

An advertisement for Denver’s first Pride, which was a “gay-in,” at Cheesman Park.

Photo courtesy Denver Public Libary Special Collections.

The group was formed the same year the Colorado Legislature overturned the state’s ban on sodomy, effectively legalizing homosexuality. For the first several months of the following year, more than 250 gay men were arrested for “lewdness,” making up 100% of lewdness arrests in Denver.

“Even though being gay was technically legal, police could arrest you for anything they didn’t like if it seemed ‘gay,’” Duffield said.

“Even though being gay was technically legal, police could arrest you for anything they didn’t like if it seemed ‘gay,’” Duffield said.

Aaron Marcus, a curator of LGBTQ+ history at History Colorado, said police were also known to raid gay bars in Denver with similar treatment to that of Stonewall.

Police also used a bus marked “Johnny Cash special,” with the promise of Johny Cash concert tickets and a ride to the show to entrap gay men. Officers would stand outside the bus at Civic Center Park — a popular cruising spot near several gay bars — and pretend to be gay and looking for other men. Police would then offer the man concert tickets to lure him into the bus, make a physical move and unless the man rejected quickly and poignantly, he was handcuffed, thrown in the back of the bus and booked into jail when the bus was full.

“It wasn’t that gay men were known for being huge Johnny Cash fans,” Marcus added. “It was that the police were just really out of touch.”

Denver Stonewall

On Oct. 23, 1973, the Gay Coalition of Denver and dozens of its allies packed the halls of the Denver City Council chambers. They demanded to stay until City Council heard their concerns and by the end of the night, council overturned five anti-gay laws: Lewd Act, Loitering for Sexual Deviant Purposes, Renting a Room for Sexual Deviant Purposes and an anti-cross-dressing law.

The City Council meeting is known as “Denver Stonewall,” Marcus said. Within the month, the group began planning for what would be Colorado’s first official Pride celebration.

On the third Saturdays of June 1974 and 1975, the Gay Coalition of Denver hosted a “gay-in” at Cheesman Park, the local park in Denver’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, where many LGBTQ+ people lived due to its relaxed zoning allowing same-sex partners to cohabitate.

Then, in 1976, activists received a permit from the city to march from Cheesman Park to Civic Center, situated between the state capitol and city hall. Thousands joined the march. The current Pride parade still follows that route.

Marcus said the march brought about 3,000 people, and if you were openly queer at the time, you marched.

“It was a show of numbers,” Marcus said. “In previous years, a lot of people sat on the sidelines and just watched, but this time, the entire community came out.”

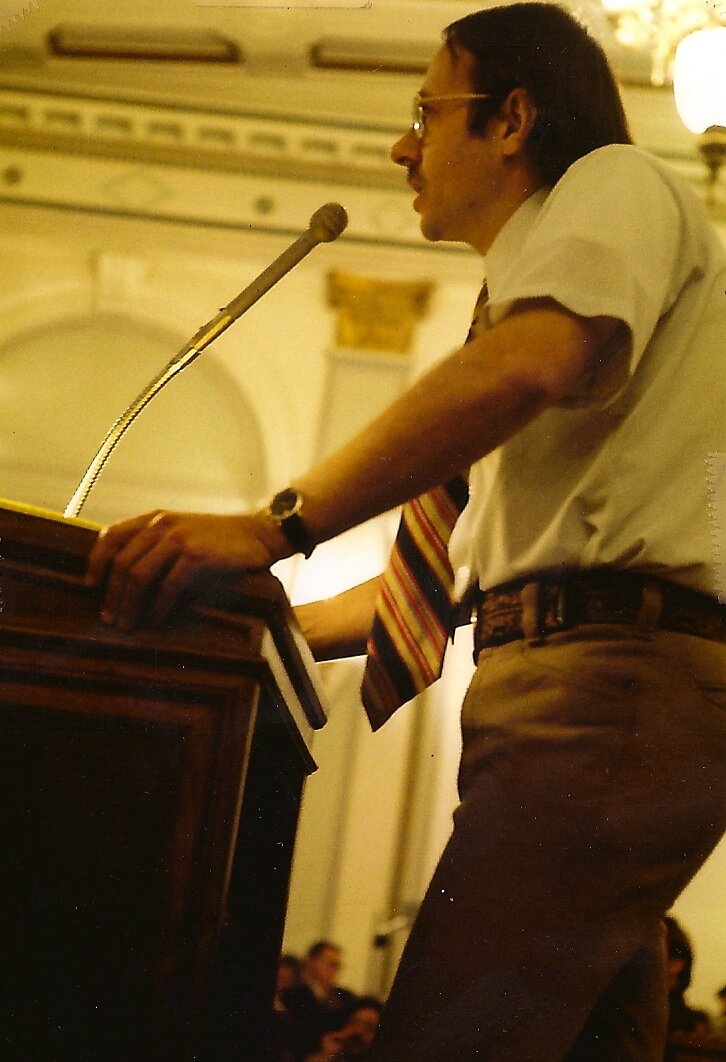

Jerry Gerash speaks to Denver City Council asking for gay men to stop being harassed by police.

Photo courtesy Denver Public Library special collections

Despite making progress with the city, many of the state’s largest employers still discriminated against their LGBTQ+ employees in the 1970s.

In the late 1970s, a group of lesbian feminists in Denver launched a boycott against Coors Brewery because the Colorado-based company supported anti-LGBTQ+ causes and discriminated against its employees.

LGBTQ+ activists teamed up with local union members to spread word of the boycott. In 1979, the brewery enacted an anti-discrimination policy.

Today, Coors Light is the title sponsor of Denver Pride, and Molson Coors, the parent company of Coors Light, has sponsored the festival for nearly 20 years.

An ignored epidemic

In 1981 and 1982, Pride transitioned from a protest and celebration to a movement supporting people living with HIV and AIDS, Duffield and Marcus said. Health officials became aware of the first AIDS case in the United States in 1981, but President Ronald Regan did not publicly mention the disease until 1985, after thousands had died.

In June 1983, activists in Denver wrote “The Denver Principles,” a self-empowerment manifesto for people living with HIV. The document outlines recommendations for doctors treating patients with HIV, people living with the disease and the general public.

“It spurred activism in Denver,” Duffield said. “Everyone turned the focus away from anti-discrimination ordinances, and it started this period of gay activism in the 70s towards healthcare and then towards fundraising for things like hospices and community health networks.”

Duffield said the AIDS epidemic impacted the entire LGBTQ+ community in Denver. Those who didn’t get the disease knew someone who did.

While the LGBTQ+ community faced rampant infections, stigma and government inaction, Pride shrunk to just a small gathering in Civic Center Park between 1987 and 1991, Duffield and Marcus said. “The public health department at the time created a public list of positive people,” Marcus said. “And that made a lot of people afraid to be around them and come out for Pride, since everyone thought of AIDS as the ‘gay disease.’”

While the time period was defined by immense tragedy, Marcus said it also created a new level of solidarity between different groups.

“Gay men were dying left and right, but a lot of lesbians and allies stepped up,” Marcus said. “That was the first time the community had come together like that in a big way.”

Pride’s return

In 1992, Colorado voters passed “Amendment 2,” which effectively legalized discrimination against the queer community. The United States Supreme Court struck down the law in 1996, but the years between took Pride out of its shadows, Marcus and Duffield said.

Colorado Governor Roy Romer, L., and Denver Mayor Wellington Webb (R.) joined activists protesting against Amendment 2, which would have legalized discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community.

Photo courtesy Denver Public Library Special Collections.

Photo courtesy Denver Public Library Special Collections.

“People were really upset, and the numbers for Pride skyrocketed because of it,” Marcus said.

In 1996, the same year the Supreme Court struck down Amendment 2, the FDA approved antiviral drugs to treat HIV and AIDS, which meant the disease was no longer an almost-guaranteed death sentence.

That year, hundreds of thousands came to Denver Pride, and the festival mirrored more of what it looks like today: massive crowds, popular entertainment and support from nonprofits and corporations.

Cops and capitalism

Fast forward to 2024: police march in the Denver Pride parade and are welcome at the festival, banks set up shop with rainbow banners and major corporations including Target and Old Navy sell rainbow clothing and accessories, a process some call “Rainbow Capitalism.”

The Denver Police Department is also the first in the state to receive accreditation for its LGBTQ+ liaison program.

“We’re now in sort of the third wave of Pride where we ask ourselves ‘what do we want this to be, going forward?’” Duffield said.

Law enforcement and corporations’ participation in Pride have been the subject of everything from academic essays to Reddit threads and news outlet opinion pieces.

“Maybe Pride is too corporate, maybe we have to ask ourselves if police should be at Pride given the history of policing against LGBTQ people in this country and the history of Stonewall,” Duffield said.

“We always have to remember that Pride really stands behind certain necessities, it has costs, it has benefits, it has debates, it has discourses, it has artwork.”

Denver’s 2024 Pride is sponsored by Nissan, Starbucks, US Bank, Southwest and other corporations. Each year for the last several years, local activists have asked The Center on Colfax to ban police officers from celebrations, claiming their presence makes queer people feel less safe and is antithetical to Pride’s roots.

While Duffield understands the concerns and said there is no “right,” answer to police presence and corporate support, Pride would almost certainly not be the massive event it is without such sponsors.

“There's marketing and money to be made but there are also many people within those communities who represent constituencies of LGBTQ+ people who are there and are advocating for these presences at Pride,” Duffield said. “There is a give and take here. Without all of that, what is Pride?”

As the LGBTQ+ community faces a record number of laws targeting it, Duffield said Pride, too, will likely keep reinventing itself.

“I think Pride, today, is about legacy making,” Duffield said. “What can Pride become and what should Pride be?”