It’s a HardKnox life: How chess is helping reduce Pueblo gang activity

share

PUEBLO, Colo. — Quiet, still, alone. It was 1996, and Mark Salazar was serving the second year of his 10-year sentence at the Colorado State Penitentiary, down from the 96 years he faced originally before accepting a guilty plea.

Salazar was still in his early twenties.

In isolation, Salazar remembered playing chess with his father and brother, both of whom were also incarcerated. Salazar’s brother was serving time in the same prison, just across the block from his own cell.

Salazar created his own chess board from memory. He sketched 64 squares on loose pieces of cardboard, and labeled paper cutouts “Q” for queen” and “K” for knight.

Salazar positioned his and his opponent’s army on the cardboard chess board, then called out his pawn’s first move.

Shortly, an inmate from a nearby cell responded with their pawn’s first move.

And so started another match of solitary confinement chess, the matches inspired Salazar to found HardKnox Gang Prevention and Intervention, a youth-focused non-profit aimed at moving fighting from the streets of Pueblo to the checkered chess boards of the local library, upon his release in 2004.

“I’m a firm believer that the game of life is very much like the game of chess,” said Salazar, now almost 50 and working full-time as a counselor and mentor for ex-offenders on parole, younger offenders on probation and at-risk youth in Pueblo.

“If you can think two, three steps ahead with respect to the game of life, you’re already taking yourself out of acting a fool before you even know it.”

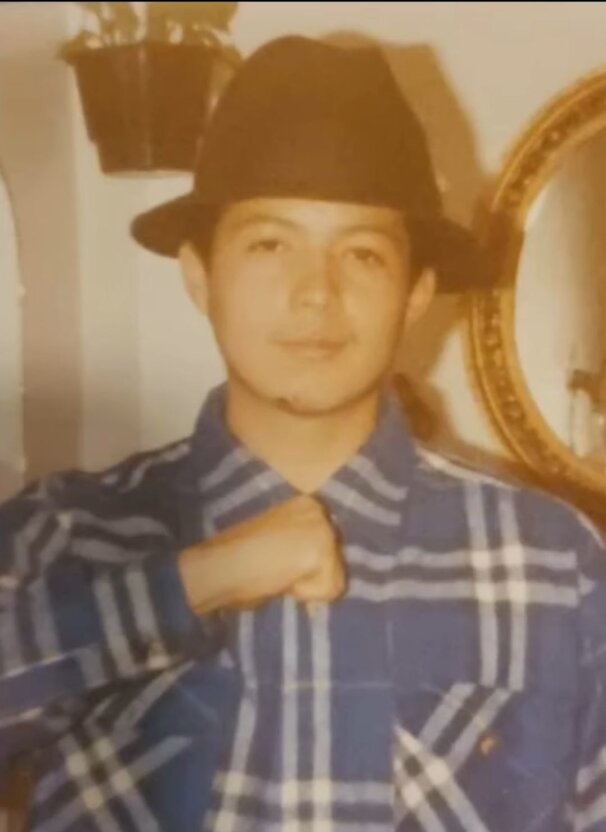

Salazar with his mother (left) and posing (right). He grew up in 80s and 90s East Pueblo.

Photos: Mark Salazar

Pueblo city officials and the FBI have recently reported significant increases in violent crime around Pueblo, some of which is believed to be gang-related.

HardKnox, which is celebrating its ninth year of incorporation this month, hosts multiple chess meet-ups every week with the goal of teaching and fostering strategic and mindful thinking that will ultimately help prevent future violence, according to Salazar.

Salazar grew up in east Pueblo surrounded by friends and family affiliated with gang culture that he said compelled him to follow a similar path.

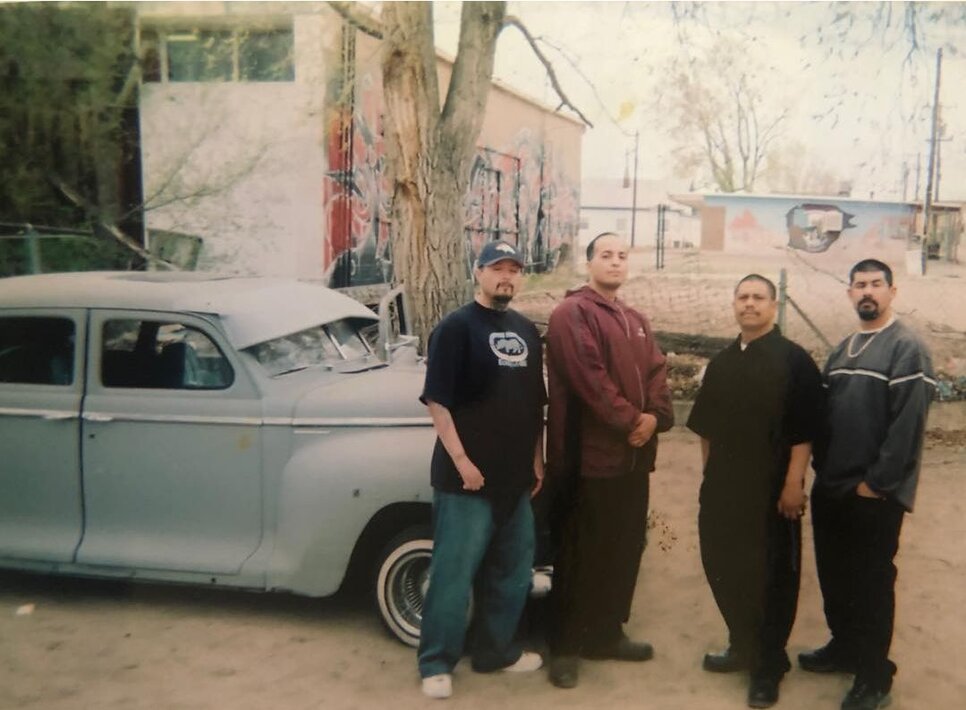

A younger Salazar (left) stands with friends.

Photo: Mark Salazar

“As ignorant as it is to say, I actually looked forward to going to prison simply because I had thought that’s where people like I belonged,” he said.

According to Salazar, he aspired to be like the “OGs” around him, a mindset that frequently led to rash and impulsive decision making.

“I was intrigued with… I’m not going to say the lifestyle, simply because that is more of a deathstyle as opposed to a lifestyle, because we all know the end result.”

In 1995, a shootout with a friend, and soon police, left Salazar near death in an ICU, and then incarcerated with a decades-long sentence at the Colorado State Penitentiary, where both his father and brother had also been imprisoned.

His brother had entered only a couple years before Salazar. While the two remained separated, they corresponded frequently via handwritten letters.

The letters, which sometimes stretched 15 to 20 pages long, helped to cool Salazar’s hot-head, and encouraged him to shift this gang mentality.

“I credit [my brother] for a lot of my successes, because if he had not taken the opportunity to challenge my ignorance, I would have continued to view life through clouded eyes,” he said.

Salazar was placed in solitary twice while incarcerated. It was in this isolation, burdened and blessed with full days alone with his thoughts, that Salazar turned to one of the oldest strategic pastimes in history.

Through HardKnox, Salazar teaches at-risk Pueblo youth to think strategically instead of emotionally.

Photo: Chase McCleary, Rocky Mountain PBS

“My dad introduced my brother and I at a young age how to play chess,” said Salazar, “but it wasn’t until I was incarcerated in prison that I played a lot of chess.”

“I spent a lot of time in solitary confinement, which is 24 hours locked down in a six by nine cell.”

Salazar constructed the chessboards he remembered from his childhood. He got neighboring inmates to do the same, and soon he and others were calling out moves across their cells.

The engaged, strategic gameplay, matched with regular correspondence with his brother, helped Salazar refocus his mindset and further realize the benefits of chess.

“[Chess] enhances your critical way of thinking,” said Salazar, “and in doing so, I was able to shift my paradigm and actually see life from a different viewpoint.”

Salazar was later released on parole after serving eight and a half of his ten year sentence. He considered himself a “short timer,” compared to the friends and acquaintances he knew who remained, sometimes indefinitely, in prison.

The transition back to life on the outside was far from smooth, yet Salazar focused on pursuing a new mission: preventing Pueblo’s at-risk “youngsters” from making the same mistakes he had.

Salazar returned to school and received certifications as an approved Treatment Provider for Adult Parole, a Certified Addiction Specialist and a Certified Gang Specialist.

After working with a number social impact organizations and establishing himself as a voice for gang prevention and intervention, Salazar cashed in his 401k to found HardKnox in July 2015.

According to him, the name comes from a conversation he had with a “heavy-hitter” while still incarcerated.

“I had asked him, ‘What do we all consider prison to be?’ and we came to the conclusion that we all consider prison to be the school of hard knocks,” said Salazar.

“And so I asked him, ‘Have you ever seen a doctor, a dentist, a lawyer, a judge go to college, obtain their degree, solidify their position in the community as such, only to go back to college to obtain the same degree?”

“Why should any of us that graduate from the school of hard knocks?”

HardKnocks now not only works to prevent young Puebloans from entering the prison system, but it assists recently-released inmates as well to help them reintegrate into society.

During the school year, upwards of 50 kids will sometimes appear at one of two local Pueblo libraries to eat pizza and play chess. Among the regulars is Iyla, a now devoted young chess player who hopes to one day compete in chess championships.

Iyla (left), who has been playing less than a year, now teaches others at HardKnox chess gatherings.

Photo: Chase McCleary, Rocky Mountain PBS

“When I started learning, I was already feeling that it was going to be one of my new passions,” said Iyla.

Iyla is eight and is heading into the third grade this fall. She started playing chess only seven months ago, though is already starting to teach newcomers to the group.

“It really gives me a strong feeling. Like I’m good at everything, and like I’m getting sharper every single time.”

Mikko, an 8th grade football player who has been coming since he was only seven, has started bringing teammates.

“Usually, none of them really play chess,” said Mikko, “but a couple of my teammates, they came here once, and they’ve been coming ever since.”

“They just get hooked… it’s addicting, you know?”

Mikko drew connections between chess to his own goals on the football field: break down the opposing line and take down the quarterback.

He also added that chess has helped keep his emotions in check and reminds him to think before acting.

“What I’m striving to do is to teach them how to think,” said Salazar.

“My hope is that these youngsters can apply that same sense of logic with respect to the game of chess, to the game of life.”