Lagers and miners and barrels, oh my! How beer came to define Colorado

share

DENVER — Perhaps the one thing Coloradans take more seriously than their outdoor adventures is their beer. And there’s good reason for it. Colorado consistently ranks at the top of the world award stage for local brews. In the recent U.S. Open Beer Championship, Colorado took home more than 35 medals in a range of beer styles from oatmeal stouts to American style pilseners to barrel-aged fruit beer.

According to the Brewers Association, Colorado had 468 craft breweries in 2023, the 4th most in the U.S., and the 5th most per capita.

But it’s been a tough past few years for beer. Last year, overall U.S. beer sales were down 5% and the number of brewpubs, microbreweries and taprooms opening their doors continued their downward decline.

Given the flux, should we continue to raise our glass to Colorado’s beer? And what can we do to make sure we stay hopped on beer and not tapped out?

To understand Colorado’s beer and how best to drink it (there actually are bad ways to drink it!), RMPBS spoke with three Colorado beer experts: Charlie Hoxmeier, assistant professor of food and fermentation science at Colorado State University as well as owner and head brewer at Gilded Goat Brewing Company in Fort Collins; Katie Strain, beverage analysis lab manager and lecturer in brewery operations at Metropolitan State University (MSU) of Denver; and Mike Jacobs, professor of chemistry and brewing science at MSU.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

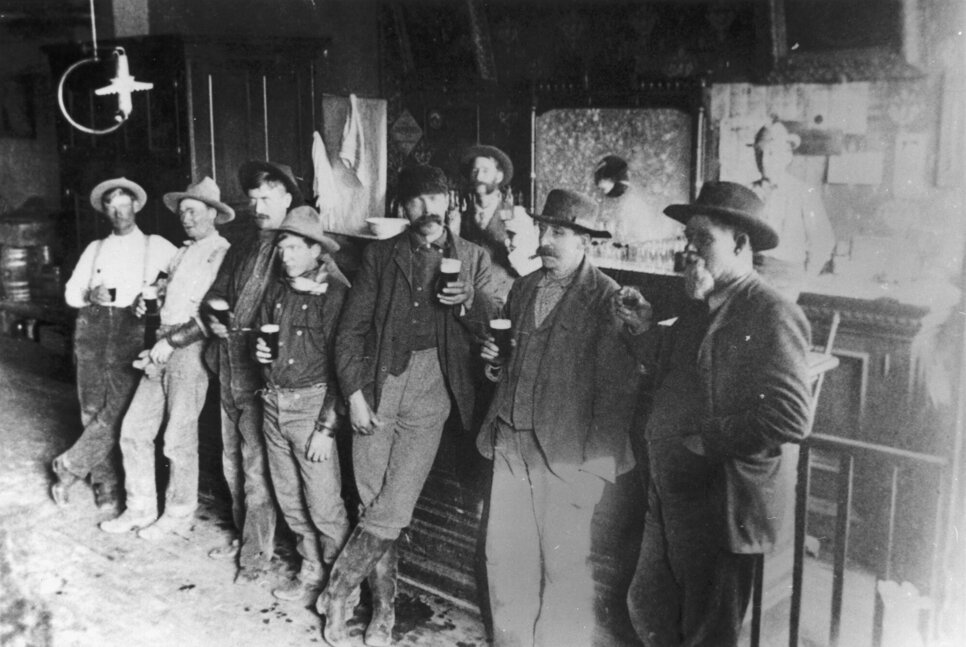

Men pose at a bar holding glasses of beer in Morrison, Jefferson County, Colorado in 1885.

Photo courtesy Denver Public Library Special Collections

RMPBS: What is the history of beer in Colorado? How did the state become such a breeding ground for craft beer?

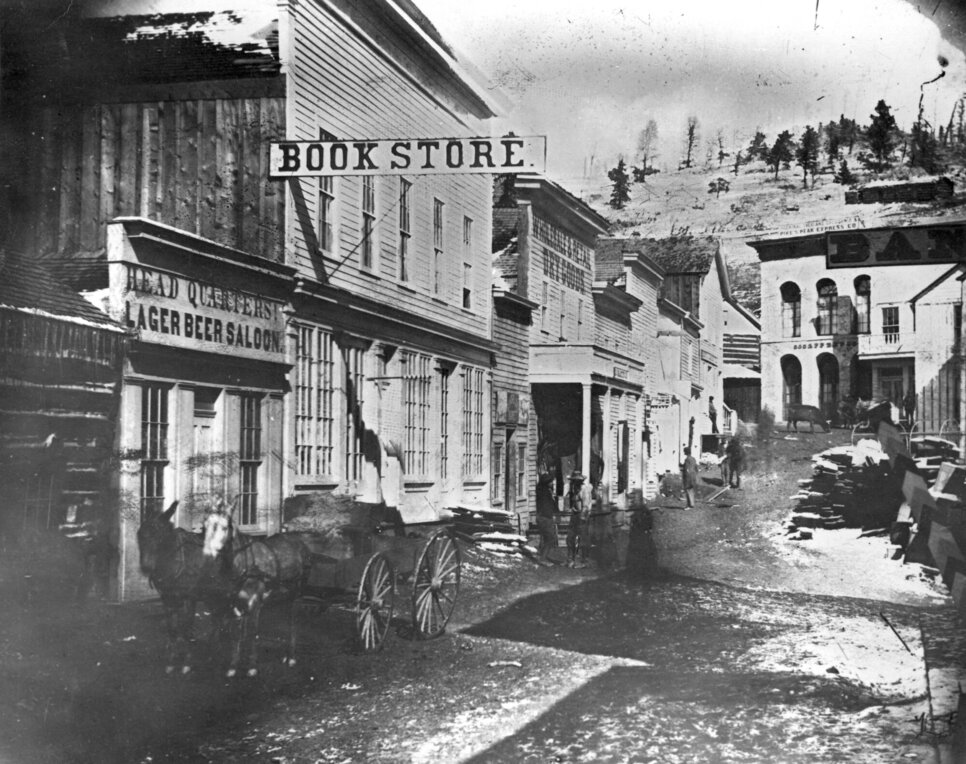

Mike Jacobs: Beer has always followed where people migrated. Colorado had a lot of mining towns and that's how beer got started here. There was once a brewery up in Black Hawk or Central City when they had mines up there.

Mike Jacobs: Beer has always followed where people migrated. Colorado had a lot of mining towns and that's how beer got started here. There was once a brewery up in Black Hawk or Central City when they had mines up there.

A winter view of the intersection of Main Street and Eureka streets in Central City, Colorado in 1862. Signs read "Head Quarters Lager Beer Saloon," "Bookstore," "Bank," "Wholesale & Retail Dry Goods," and "Central Overland California & Pike's Peak Express Co."

Photo courtesy Denver Public Library Special Collections

Charlie Hoxmeier: For thousands of years, beer has also been safer to drink than water. There's a step in the production of beer where you boil the liquid, which sanitizes it. They [miners] could have a safe source of hydration with the water that was in the beer.

For the most part, the beers that people were drinking in those [mining] days was fairly low-alcohol.

Beer and bread baking was also associated with the domestication of barley and the agricultural revolution. Growers could preserve their barley store by fermenting it.

And then beer became part of the fabric of life in Colorado. It's just what people do here.

Katie Strain: We are lucky that on campus we have the Tivoli Brewing Company. Tivoli is the oldest brewery [still in existence] in Colorado and the building still stands on our campus.

Tivoli Brewing Company today and in the late 1800s (L to R). The original building still stands on Metropolitan State University of Denver’s campus and now serves as the Auraria campus student union.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

RMPBS: Is there something unique to Colorado’s water that makes it particularly suitable for making beer?

CH: It's fresh runoff and really soft, low minerality water, which is important for brewers. We’re able to do a lot with our water that other regions of the country aren't able to do – or at least not without a lot of effort.

Half the country is operating on really hard [high minerality] water. There are some beers that you can make with really hard water, or you need to go through extra processes to remove some of those minerals and be able to brew with it.

Water makes up 90% of beer. So we have to manage and understand our water really well to be able to have a high quality and consistent product.

Nowadays, because we understand water chemistry so well, there are fewer impediments to making any style of beer regardless of the water source. That's part of the reason that Anheuser-Busch has developed such an amazing brewery. They can brew Bud Light at 12 different breweries all across the country with different incoming water, and that beer tastes exactly the same regardless of where you buy it.

MJ: So today anybody can make beer as long as they have the money and the resources and the ability to clean their water and adjust it how they want. But that costs money. Colorado had an advantage a long time ago.

RMPBS: Given Colorado’s particular water compounds, is there one type of beer that’s innately brewed better here?

CH: Historically, there's a lot of relevance to that question. Brewers made Guinness in Dublin, porters in London, malty beers in Munich and light Czech pilsners in the Czech Republic. All of those beers were originally developed because that's the style of beer that they could brew with the water they had.

If we [Colorado brewers] didn't do anything to our water, our beer would probably be most similar to the beer from Pilsen in the Czech Republic – those really light, malty pilsners. That would be the style of beer that would be best for us to brew.

But now we understand water chemistry so well that we can make anything. We can add minerals to the water and do all kinds of things.

RMPBS: In Colorado, brewers aren’t literally walking to the river to take fresh water, right?

KS: No. Most breweries use municipal water. Breweries can and should request water analysis reports from the water companies a few times a year, because snowmelt, runoff and drought can impact the water chemistry at any given time. Denver had to increase the pH of their city water a few years ago because of the lead pipes, so brewers had to adjust for the change in pH as well.

Chlorine is another big issue. Water treatment facilities will add chlorine into the water, which can cause weird off flavors in beer. So it’s important for brewers to remove that chlorine when making beer.

RMPBS: What does it take to become a brew master?

CH: Blood, sweat and tears? People don't get into the brewing industry to get rich anymore. That ship has sailed. You do it because you love it.

People who graduate from both of our programs probably have the skills to step into the head brewing position. But it's a very competitive industry and people tend to stick around for a long time, so it's hard to get your foot in the door. You really have to show up with some integrity and work ethic and be willing to bust your ass.

MJ: In the past, beer making seemed to be very secretive. You would go to certain schools in Europe and if, say, you learned beer in Germany, you’d learn it the way they wanted you to learn it. If you’d go to England, you’d learn it the way they wanted you to learn it. Now I think it's starting to cross lines and become more open to different styles and methods.

CH: If I can backtrack a little bit, the designation of “brewmaster” is usually reserved to somebody who has completed an advanced degree from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling School in Europe. That's where the term originally come from. The term “brew master” has been thrown around a lot, but “head brewer” is basically that position and the proper term for most people in the U.S.

RMPBS: You three are professors in brewing programs on college campuses. How popular are these programs? I imagine they would be a big draw for college students.

CH: We [CSU] were one of the first university-based brewing programs in the country, along with UC Davis, Oregon State University and Appalachian State University. We started our program in 2013. Now there are well over a dozen programs. So the environment has certainly changed in the last ten years or so since we've been open. There are more schools to choose from and a lot more opportunity for students. Our enrollment is down a little bit, and I think that's because of the other schools that are now available.

A lot of our students think of it as a brewing program without knowing much about brewing. Then they walk in and they have to take classes in organic chemistry, physics, biochemistry and microbiology, and they're like, “Wow, we thought this was the beer drinking program.”

We take a fairly heavy food chemistry approach to it, and that weeds out some students that don't quite have that commitment. I think it's important to express and relate to the students how science-heavy brewing is.

The lab at Metropolitan State University of Denver has a gas chromatograph that measures the concentration of chemical compounds in beer such as alcohol, aromatics and off flavors.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

KS: A lot of our students are looking for a second career. We get a lot of people using the Veteran’s Assistance program. They’re on average a little bit older than people coming out of high school that have never had a beer legally.

MJ: I would add that even though they're getting a degree in fermentation and beer, they can do other stuff, too – they can work with anything that deals with fermentation, like yogurt or breads.

KS: We’ve had graduates go on to Coca-Cola and Pepsi.

CH: We always say that beer is our model. We're teaching beer, but we’re also teaching you how to think and understand the importance of cleaning and data and good science. You can take that information anywhere, even to, say, pharmaceutical production, which in a lot of cases is fermentation-based.

RMPBS: Do you need proper schooling and a bachelor’s degree specialized in the profession to get into the field?

CH: It's starting to be that way now. The older generation of brewers went to the school of hard knocks and they just got on-the-job training and figured it out as they went. But similar to other industries today, there is an expectation of a bachelor's degree in something related to brewing to be able to get into it.

RMPBS: Is water conservation a big issue in brewing?

KS: Coors is among the best in the industry when it comes to water conservation. They have about a 3 to 1 water to beer ratio which is really good. Most craft breweries, if they're good with water conservation, are probably closer to a 10 to 1 water to beer ratio. But water is used not only in brewing, but a lot of it is used in cleaning and sanitizing.

CH: The very big breweries that have 24/7 automated operations have much more opportunity to harvest the energy they get from the hot water and use it in other processes.

So it's easier for them to do that at scale. It’s much more challenging for smaller breweries to reclaim and reuse that water.

If we include barley farming in our analysis of how much water is used, it's an over 60 to 1 water to beer ratio - and brewers have no control over that. So when we get the farmers and the hop growers involved, that's when [the question of water conservation] becomes more relevant.

RMPBS: Besides water, where are most of the ingredients for beer coming from?

KS: A lot of malt gets imported from Europe and Canada. Obviously importing malt from Europe is expensive, but people like those malts.

If you drive down I-25 there’s barley farms for Coors and Budweiser.

Hops don't grow particularly well in Colorado – they require a little bit more water than what Colorado provides. The main hop growing regions are the Pacific Northwest and some northern states like Montana and Michigan.

CH: I'm biased because I'm a microbiologist, but the microbe is the only required ingredient. You can make beer without barley. You can make beer without hops. But the one thing you do have to have is a microbe. Yeast [a type of microbe] is responsible for making most of the alcohol and CO2. The cliche brewers joke is that: brewers make wort and yeast makes beer.

There are particular beers that taste the way they taste because of the yeast selection.

[Note: Wort is unfermented beer made by converting starches of malted grains into sugar].

RMPBS: Where can you get these microbes for the yeast?

CH: There are yeast labs all over the place. That's the modern option. The old way, before we knew what yeast was, was to just put a tank outside and capture it in the air. For example, the Belgians would put a big tank of wort – unfermented beer – outside overnight and capture all of these microbes.

RMPBS: How are breweries doing from an economic standpoint right now?

KS: This last year was really the first year in decades that craft brewing kind of hit a flat plateau, where the number of breweries opening nearly equaled the number of breweries closing. It’s a crazy time for craft brewers, for sure. There's a lot that they're competing with. The cost of everything has gone up, but the price that they’re able to sell beer for has not quite kept up with that.

CH: We're all in a state of flux right now. Beer as a beverage segment is down dramatically. And inside of that, craft beer as a segment is down dramatically. People are drinking less and they're spending less.

KS: Distribution has become very challenging for a lot of the mid-level craft brewers, because they're competing now with ready-to-drink cocktails, hard seltzers, hop waters, hop teas and nonalcoholic beers.

Gen Z also doesn’t have the brand loyalty that the older generations had. This younger generation is more interested in trying the newest thing and the most unique flavors, so there is no guarantee that they are going to keep coming back to the same place over and over again. And there's more of a focus on hospitality than there used to be, so it’s important to make sure you provide really good customer service and a welcoming atmosphere.

CH: The two questions that I get most often in the brewery is, where is that one beer that I always get when I come in, and what do you have that's new? So I have to cater to both of these people all the time.

The Brewers Association did a survey a couple of years ago and asked general craft beer consumers: Why do you go back to any one place? And number three on the list was the beer. So they're not going for the quality of the beer necessarily or the availability of styles. They're going because of the environment and the hospitality that they felt. So good beer is a necessary but insufficient condition to keep your brewery operating. You have to do so much more.

RMPBS: Restaurants are known for being a notoriously hard business to survive in. Are breweries in the same category?

CH: The margins in a brewery are a lot better than a restaurant. Restaurants traditionally have very tight margins, so they have to turn tables very often to get people to come in, buy their food and leave. We have better margins in a brewery, especially if we're not distributing.

If people are coming into my brewery to buy beer on draft, my margin is 80%. As soon as I put that beer in a can, bring it to a liquor store and sell it to somebody that I don't get to talk to, my margin is like 15 to 20%. So I have reasons to get people to come into my place as opposed to sending it out the door.

RMPBS: What are the biggest trends in beer right now?

KH: If you go to breweries, a third to maybe half of them have some sort of flavoring like watermelon or mango or pineapple or something like that. When you go to conventions, there are so many companies selling flavoring additives. Gen Z is always interested in new flavors – and the flavors are starting to get more exotic. It's not just the typical strawberry or watermelon flavors. They're looking for some of the more exotic tropical fruit extracts.

CH: A lot of it feels really gimmicky – and it is pretty gimmicky, like the glitter beer or smoothie sours – things that make brewers cringe. The last big trend that people jumped on was seltzers, and that's a stressful fermentation. That's hard for brewers to do well. So that took a lot of time for brewers to figure out.

The other issue we now have to deal with is the food safety issue associated with these popular low and non-alcoholic beers. A beer is shelf stable in a lot of ways because it has a low pH and alcohol in it. When we're raising that pH and removing the alcohol, that's a recipe for making people sick. It's a pressing issue within the industry that small brewers in particular need to be very aware of.

RMPBS: Is there actually a glitter beer, by the way?

KS: Oh, yeah. I saw a TikTok of champagne and cotton candy and glitter and I was like, “that looks gross.” And I had students in my home brewing class who wanted to put edible glitter in one of the wines they made. I said, “It’s your wine. You do you.”

RMPBS: What’s the professional beer community in Colorado like – is it collaborative or competitive?

CH: We're all fighting for the same customers, so it's incredibly competitive, but we're all friends. We all want each other to do better. There's a Google group of all of the Fort Collins brewers, and when somebody needs something or they run out of something, they post to the group. And it's almost a fight to be the first person to respond and help out. It’s the cliche of the “rising tide lifts all boats.” We all want to see everyone do well.

I don't want to see a single brewery close down. That would help my business if one did, but I don't want to see anybody close down, and I don't want to see anybody make bad beer.

But when a new brewery opens up, there isn't suddenly a new population of people over 21 that's created with that brewery. They're taking them from other places. So we're all fighting for the same customer. It's unlike any other industry I've ever been a part of in how competitive and collaborative it is at the same time.

Glass bottles allow light in, which can cause chemical changes in beer and an unpleasant “skunky” taste. Brown bottles tend to let less light in than green or clear bottles.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

RMPBS: Is it better to drink beer in a can, glass or on draft? Does the way it’s served affect the flavor?

KS: You want to drink draft beer whenever you can, as long as you're drinking it from a place that takes care of their draft lines. Even if you're drinking beer out of a can or a bottle, to get the best experience you should be pouring it into a glass. So draft is always best.

Otherwise I would say bottles are probably second best. Sometimes you can buy bottle conditioned beers. A lot of the Belgian imports and some of the German imported beer are bottle-conditioned. Instead of being force-carbonated, they're carbonated naturally with yeast in the bottle. So that's a cool thing you can get in bottles that you can’t get in cans.

MJ: But bottles can let in light and cans can’t. But I agree with Katie that draft definitely tastes better. I think with Heineken – the bottle definitely tastes different than the can.

CH: Corona in a clear bottle – that flavor is going to change as soon as it’s exposed to light. And that delicious 8% IPA with a really delicate balance of hops that you just paid $10 for in a brewery, as soon you sit out on a patio, that beer flavor will change in a second, as soon as it’s exposed to sunlight. So there are reasons to keep them covered in a can.

You want them poured out for the best sensory experience, but for beers that are expected to have very little sensory experience, you want them as cold as possible and drunk from a bottle or a can.

The company Rolling Rock adds a particular off-flavor back into their beer because people now associate this off flavor with their green bottle packaging, which lets in light and causes this chemical reaction that makes it taste skunky. So even though Rolling Rock makes excellent beer and stores it well, they add this chemical back into the beer because people got so used to the off-flavor in the bottles.

RMPBS: So we should all stop drinking beers outside on rooftops?

KS: Yes, but most people won’t notice the difference or have any idea what’s happening, unless they’re trained to be able to detect that off-flavor.

But I've seen outdoor beer festivals pouring the beers and letting them sit out until somebody comes to get them. Don’t do that!

RMPBS: Does the shape of the glass matter?

KS: In Belgium, it seems like they have a different glass for every type of beer. In Germany, almost every beer style has its own glassware. If the beer glass is shaped more like a wine glass, it can help concentrate aromatic compounds, so you get a better aromatic experience from the beer.

Usually what you see in the United States is the standard shaker pint. It’s just your standard beer glass, and that really doesn't help the beer in any way, sensory wise.

Even the thickness of the glass and how it distributes beer throughout your mouth can change the experience. There’s been studies that show how colored glassware or the color of the walls inside the brewery can impact the way people taste beer. For example, people associate certain colors with sweet or sour flavors. There’s a lot of cool research looking at manipulations of settings and how that affects the way consumers perceive the taste and flavor of beer.

RMPBS: What is the best beer you’ve ever had?

KS: I have a few. I’m always really excited about Flanders red ale. The one that I like is the Duchesse De Bourgogne. It's a Belgian ale that is aged in wooden barrels that contain these resident souring and wild microbes. It’s got brettanomyces and lactobacillus and acetobacter, so it actually converts some of the alcohol into vinegar, into acetic acid. It's just this really cool, complex deep beer that I'm always excited to have.

Charlie gets in trouble every time I go to Gilded Goat because he's always out of my one of my other favorites, which is, Lightfoot. It's a coffee pale ale. I love that beer, and he's always out of it, so he hears it from me.

Otherwise, I really like German lagers. They're clean, they're malty, they're simple. And English bitters are my other favorite style of beer.

CH: I like smoked beers. They're called Rauchbier in German. There's a famous city in Germany called Bamberg where you can smell the smoked malt as you drive into the town. They use oak or beechwood or peat and smoke the malts and then brew these Rauchbiers with these smoked malts. They have a really distinctive flavor. They can be a little phenolic and spicy and peppery, or they can be like cured meat. There’s such a broad range of flavors that come through, and I fell in love with those. Alaskan Smoked Porter was my first introduction to them. I would love to make those types of beers [at my brewery], but they wouldn't sell.

I also love English bitters, but I can't put a beer on my menu that says “bitter” in the name because nobody would buy it. That means English pale ale to everybody else, but to the average consumer, an English bitter means: “Gross, bitter. Why would I buy that?”

MJ: I prefer lagers, but I like to try a lot of new, different beers. I'm going to steal an answer I heard from a brewer once, “the best beer I’ve ever tried is the one I haven't had yet.”

RMPBS: Anything else you want to share?

MJ: I think Ben Franklin said something like, “Beer is the reason God wants us to be happy.” Was that the right quote? I saw it in an airport.

KS: “Beer is constant proof that god loves us and loves to see us happy.” But I had a student tell me that he actually said that about wine, so I don't know.

CH: It was about wine.

KS: I like it better about beer, so ill stick with that (laughs).