How landscaping plays a key role in the fight against climate change

DENVER — Turf grass is the largest irrigated crop in the United States, taking in more water annually than all corn, wheat and fruit orchards combined.

For states like Colorado that are facing consistent drought amid a warming climate, is it justifiable to expend that much water — nearly 9 billion gallons per day are spent on landscape irrigation across the U.S. — on a crop that is largely decorative? Many experts are saying “no.”

The solution, they say, is xeriscaping.

A history of opulence

How did we get here? The quintessential American front yard — a manicured plot of verdant, 2.5-inch-tall Kentucky bluegrass — dates back to European colonists settling in what is now North America. The cattle Europeans imported consumed nearly all native grasses in the colonies, so the colonists relied on the grasses from European seeds to feed their livestock (turns out “Kentucky” bluegrass is actually native to Europe and parts of northern Africa).

Although it was not native to the East Coast, that grass was at least functional because it fed animals. It wasn’t until figures like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson came along with their shared admiration for European landscaping that “non-functional turf” rose in popularity.

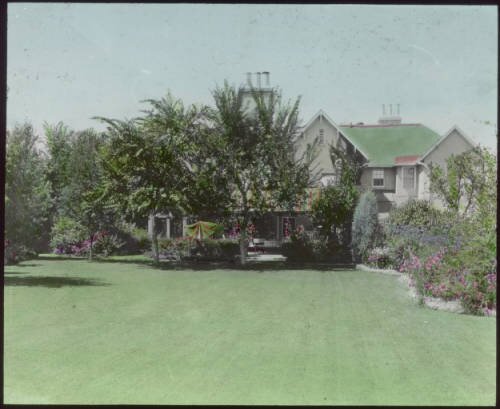

In places like Great Britain, these types of lawns were used as a status symbol: the rich could afford to own swaths of land that were purely ornamental, whereas working-class families needed to use what little land they did have to grow crops. Washington and Jefferson, both slave owners, copied this model by implementing sweeping lawns at Mount Vernon and Monticello, respectively, making non-functional turf an aspiration of the land-owning rich for centuries to come.

A trio of lantern slides from the 1930s show the lawns belonging to members of the Garden Club of Denver. The third photo is titled "opulent grounds." (Credit: Denver Public Library)

Following the Civil War, suburban neighborhoods became increasingly popular — due in large part to racial integration in cities — and lawns did, too. Front lawns became a symbol of prosperity, conformity and triumph over nature.

In Colorado, an increasing number of homeowners are eager to let nature win.

A lazy gardener is a waterwise gardener

When John and Sarah Claus decided to replace their home’s turf with drought-tolerant grasses, they called Lakewood’s code enforcement division.

“I filed a complaint against ourselves just to do a good-faith sort of thing,” John said.

The family’s new yard, comprised of wheatgrass, fescue and rye grasses, was going to look a lot different than most lawns in their neighborhood in that the grass would be much taller and relatively unruly in comparison to neighboring yards, many of which looked like the left-center gap at Coors Field.

“This is not what most people think of when they think of a lawn,” John admitted.

The Claus family chose to landscape with drought-tolerant grasses for a large section of their yard because they still wanted an area for their kids to play outside.

Despite some questions from neighbors and even some official complaints, Lakewood’s code enforcement team — which states “grass and weeds cannot exceed a height of six inches on residential or commercial property” — has not caused the Clauses to make any changes to their yard.

The family felt an environmental obligation to cut down on their water usage, as climate change continues to warm Colorado and water becomes increasingly scarce. The Clauses only water once a week during the peak heat of the summer, and their water bill is significantly lower than those of their neighbors, they said.

A lack of constant maintenance also attracted the Clauses to xeriscaping. “I think we’re both lazy gardeners,” John chuckled. “So, if we can get something else to do that job for us, that would be ideal.”

In their case, that “something else” was rainwater. By using rain barrels and intentionally diverting their downspouts to certain parts of the yard, the Clauses don’t rely on hand-watering or sprinklers to the degree that many of their neighbors do.

“Let’s not use potable water to water the earth,” Sarah explained. “And let’s not tap into an aquifer for non-conducive grass to grow here.”

There are also aesthetics to consider. While many people are attracted to a manicured green yard — author Michael Pollan has questioned if our proclivity for lawns is partly genetic, as open grassland represented safety to early humans — there is a different beauty that comes with native plants. The petals of coneflowers, for example, add bursts of pink and purple throughout the yard.

Coneflower adds pops of color to the Claus' yard in Lakewood.

“I love looking out and seeing how many animals, in one moment, can be enjoying the yard. I think that is what we wanted. We wanted that richness, and there’s so much more life that happens,” Sarah said. “Not only are we not having to deal with gas or the emissions from the lawnmower, but [the yard] is a habitat instead. It’s not supposed to just be ornamental.”

Xeriscaping’s Colorado roots

Denver Water coined the phrase xeriscaping in 1981, combining “landscaping” with “xeros,” the Greek word for dry. Xeriscaping is based on seven principles: plan and design; soil amendment; efficient irrigation; mulch; plant zones; alternative turf grasses; and maintenance.

[NewsHour: What is xeriscaping? How you can turn your lawn into a sustainable oasis]

Xeriscaping looks different depending on the climate. No matter where you are, though, the commonality will be that the landscaping prioritizes using as little water as possible. That doesn’t mean it’s all just rocks and cacti, and as local governments incentivize homeowners to conserve water, people like Anna Hoover are prepared to show Coloradans how beautiful — and easy — a xeric landscape can be.

Sunflowers are on full display at the Majestic View Nature Center's demonstration garden.

Hoover is the director of the Majestic View Nature Center, the environmental education hub for the City of Arvada. Prior to 2008, the nature center was a private residence with exclusively turf grass. Now, the area showcases a sprawling demonstration garden with sunflowers, coneflowers, milkweed, succulents and many more species.

The garden exists to show Arvada residents the possibilities of xeriscaping. At 25,000 square feet, the space can be overwhelming to prospective gardeners and landscapers who don’t know what to plant first.

“A great way to start is to find out what you want to do in your garden,” Hoover said. If you want birds, butterflies, bees or small mammals in your yard, for example, “that can help direct you to what plant species to select.”

Anna Hoover is the director of the Majestic View Nature Center in Arvada.

This year marks the 20th birthday for “garden in a box,” a plant-by-numbers kit of waterwise plants and flowers distributed by Resource Central, a Boulder-based conservation nonprofit.

The nonprofit’s direct-to-consumer gardens are one of the most popular ways that individuals and municipalities transition to xeric landscapes. When the program started in 2003, Resource Central delivered 100 gardens. In 2023? Eleven thousand.

Ali Colbert, senior program coordinator for garden in a box, said people can purchase gardens from Resource Central twice a year — in the spring and again in the fall. Spring, she continued, is when they get most of their business, because customers are a bit stir crazy after the winter months. Because they sell out in a matter of weeks, Resource Central is encouraging more people to plant in the fall.

“Right around now is a great time to plant,” Colbert said. “The soil is warmer and the plants are also not focused on producing a bloom; they’re more so focused on growing their roots down.”

Phebe Taylor, program manager for garden in a box and Resource Central’s waterwise yard seminars, said fall is the ideal time to plant.

“We’re definitely working on greater supply and educating the public a bit more about fall,” she said. “It’s the least water-intensive time to start a garden.”

Taylor said recent research found that a 100-square foot waterwise garden saves 1,000 gallons/year compared to Kentucky bluegrass, but she believes it could be even more.

“Perennial gardens are estimated to thrive seven to ten years on average, and many go much longer than that,” Taylor said. “So that is about 7,000 to 10,000 gallons over the course of their lifetime and I think that’s quite conservative.”

Taylor and Colbert met with Rocky Mountain PBS outside Lafayette Fire Station No. 1. Just two years ago, the lawn was made of turf. Now, it’s a colorful demonstration garden filled with waterwise plants, much like the garden at the Majestic View Nature Center. We have Pete Bradshaw to thank for that.

When Bradshaw was namedLafayette fire chief in the spring of 2021, he got word that the firefighters were tired of mowing and watering the station’s lawn, which nobody used. He teamed up with Elizabeth Szorad, the sustainability manager with the City of Lafayette, to come up with a solution.

Szorad had been receiving a lot of calls from Lafayette residents who wanted to convert their yards to a xeric landscape but didn’t know how to start or what it could look like. She and Bradshaw decided to use a garden in a box from Resource Central to create a demonstration garden.

The Lafayette demonstration garden intentionally includes waterwise turf to show visitors that you can xeriscape while still having grass in your yard.

“Everybody should do this,” Szorad said. “Our climate is changing. It’s the most impactful and resilient thing you can do, especially with how snow is being impacted in the Rocky Mountains, the heat, the air quality. Gardens are a really great tool for carbon sequestration and supporting wildlife.”

As one may have surmised from its name, Resource Central has a lot of information and tips on its website for prospective xeriscapers. For more resources, people should visit their local Colorado State University Extension office. Rocky Mountain PBS interviewed six people for this story, and every single one of them mentioned the CSU Extension, which dates back to 1914, as the best place for information on native plants and waterwise landscaping. You can find many resources on the extension website, but if you prefer an in-person experience, every county in Colorado has its own extension office.

Patience, patience, patience

A stunning oasis like the two demonstration gardens mentioned in this article do not happen overnight. For starters, the plants need time to come into their own, and that’s not a process that can be rushed.

“Any area that you’re going to restore, whether it’s a garden or just native open space, it’s going to take that three-to-five years for things to find their sweet spot,” Hoover said. “You won’t really see what the long-term look of your yard or garden will be for at least those first two to three years. You’re going to be fighting some of the noxious weeds that are going to fill in quicker and get established quicker.”

Secondly, there is what the Claus family described as “analysis paralysis:” many people never make it past the planning stage because they don’t know where to start or they want to landscape the whole yard at once. The Clauses, as well as Hoover, recommended starting small by replacing one section of the yard and expanding the project over time. That way, you’ll also be able to learn which plants do and don’t thrive in your yard.

“Perfect conditions, perfect soil is not the goal here,” Colbert said. “It’s kind of more about adaptability and resiliency.”

However, that patience and resiliency will pay off. The upfront cost of a landscaping project can be expensive depending on the size (and especially if you hire professionals), but Lyle Fair with Environmental Designs said the project will eventually pay for itself.

Fair said that if someone replaces an average front yard and makes it fully xeric, they can expect to reach their return on investment in about six years. That means the money people save by not having to water their lawn as much will be more than what the landscape project cost. An important note, Fair said, is that that estimate is based on current water prices.

“As those rates continue to go up — and we have not seen any price per gallon go down in the past 20 years — that would only shorten that return on investment,” he said. “And there’s no signs that rates are going to go down for water.”

The power of collective action

It can be difficult to not feel a sense of powerlessness when considering the impact of individual action in the face of climate change. Only half of Americans feel like their personal choices have an effect on the climate crisis. Can you blame them? A recent study found 20 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions come from home energy use. Transportation and industry, meanwhile, are responsible for nearly 60 percent of emissions — so do personal landscaping decisions really make a difference?

“What if everyone had that same mentality of we’re screwed, we’re just going to keep doing what we’re doing? If everyone just does a little bit, as best as they can, collectively they’ll see a difference, especially with landscaping. This is noticeable,” said Szorad, gesturing to the demonstration garden in Lafayette. “People will be interested and want to find out more.”

Fair was more direct. “We can’t continue on the road we’re on,” he said in reference to traditional turf lawns, “or we will run out of water.”

Colbert said xeriscaping is powerful because, compared to other “green” actions like recycling, making changes to one’s yard feels more immediate.

“I think personal landscape change is a unique individual action because it has you actually working outside, in the dirt, dealing with the climate, thinking about the weather, thinking about how it’s changing in a really tangible way,” she said. “So it feels different than the action of recycling because it is really connected to what’s going on. It’s a gateway into appreciating more about your surrounding area.”

Kyle Cooke is the digital media manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at kylecooke@rmpbs.org.