A 45-year partnership on display across two Colorado art galleries

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — Motioning over her Tejon Street balcony to the whirling traffic and jackhammers below, retired English teacher Wylene Carol reminisced about moving in two decades ago. “There were very few restaurants, and only a bar or two,” she said of what is now the fastest-growing city in the state. “Downtown Colorado Springs was tiny.”

There was just one item on Carol’s list of home-hunting "must-haves" back in 2001: Plenty of wall space to hang art. Spurred by her desire to showcase a unique, single-minded collection, Carol chose this loft apartment — one of the first built in the city — “because of the tall ceilings,” she said.

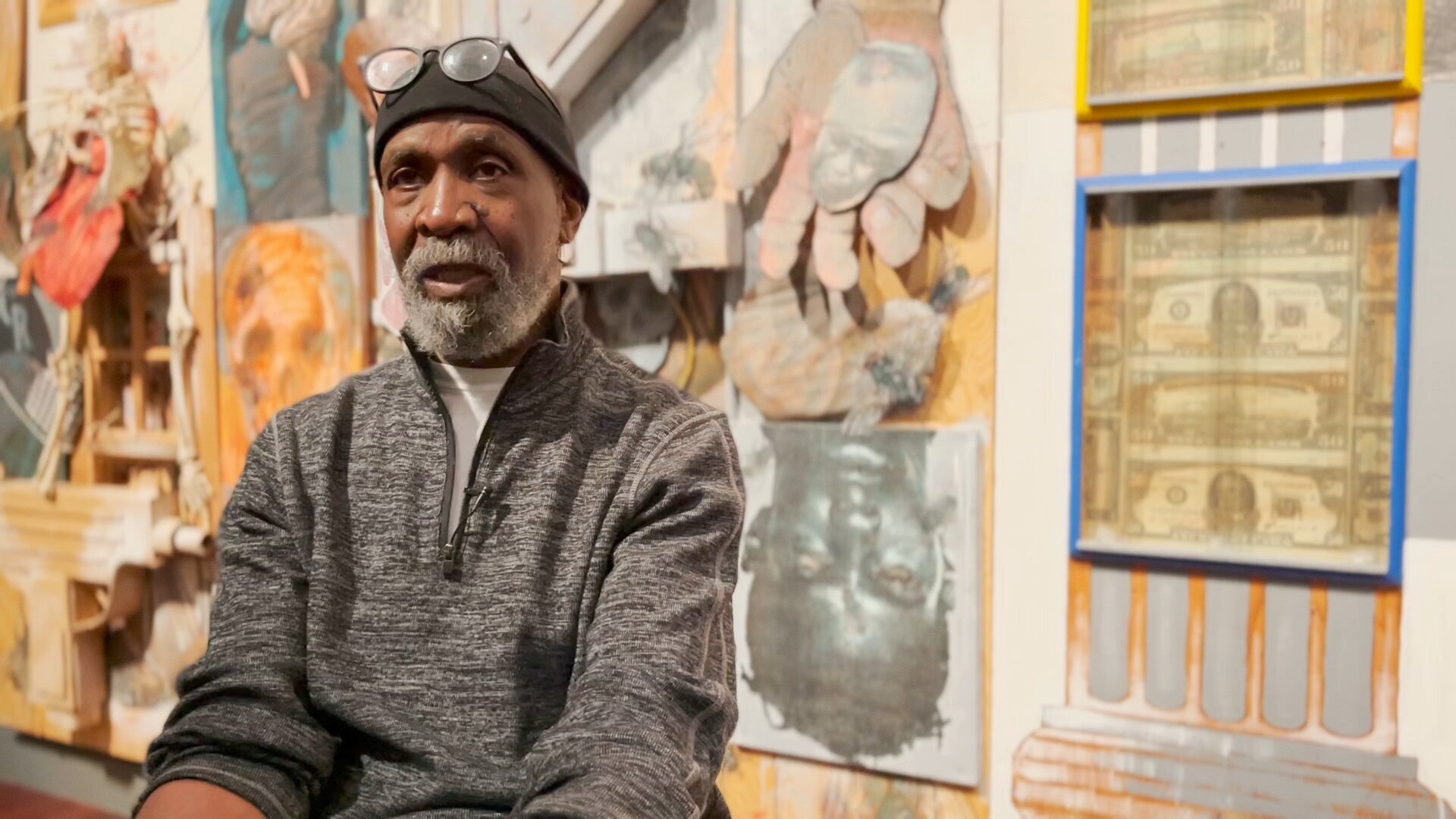

It boasts ample room, yet the second-story space gives attention to just one artist. The walls, ceilings, corners, and table top almost exclusively feature multi-media creator Floyd D. Tunson, whom Carol has managed for 45 years.

“My apartment is filled with pieces by Floyd Tunson. And I dare say, there's hardly anywhere in Colorado Springs that has the collection of contemporary art in one place that I have,” Carol said. “That's really one of the very selfish reasons for which I work with Floyd,” she laughed. “I get to hang great art in my place!”

Spanning a five-decade career, the dozen-plus Tunson pieces in Carol’s home represent an eclectic body: multi-media wood and metal works, paintings, prints, sculpture, rubbings, drawings, graphic art, abstractions, installation — even two replicas of cake.

It’s “a perk of the job,” Carol said. “He just gives me work sometimes. Mostly, it’s all just temporary, until somebody buys it — or until I want something new.”

Carol’s residence could be listed as the fourth, unofficial location of this summer’s “Tunson Takeover,” as she’s dubbed the 50-year survey of the artist’s repertoire exhibiting across the Front Range.

“Floyd D. Tunson: Ascent,” encompasses 10,000 square feet spanning two Denver metro galleries. RedLine Contemporary Art Center hosts “Ascent” through July 31, with the companion show “Ascent” exhibiting at the Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities until August 28.

“It’s sort of a homecoming,” said Co-Curator Daisy McGowan, who purposefully brought a proposal to celebrate Tunson’s work to RedLine because “it’s part of the neighborhood where Floyd grew up,” she said.

“Denver was a great place to grow up,” Tunson said of Five Points. He went to East High School, one of the ten best in the nation. His family moved to the Platte Valley Projects, then eventually moved again. “As most Black people were starting to move across York Street, we moved across York Street to Fillmore Street,” Tunson said.

He was raised in a creative family, particularly inspired by the talents of his older brother, artist Michael Tunson. Representation, Tunson said, was slim. “There was a Black sign painter who painted all the windows in town. I thought I would grow up and be an artist like that,” he said.

It was one Mrs. Robinson at the Ford-Warren branch of Denver Public Library who first introduced resonant fine art to Tunson, he said. “Mrs. Robinson was so great. She turned me on to Charles White and Jacob Lawrence. Charlies White then became the epitome of what I wanted to accomplish as an artist — after my brother,” Tunson said.

This cross-venue exhibit morphed out of pandemic delays at both RedLine and the Arvada Center, McGowan explained. “We took the structure of the exhibition I had already curated and designed for RedLine – a survey of 10 major bodies of work, with significant works from [Tunson’s] abstract series – and doubled it across the two spaces,” she said. “The concept became, if you see one of the exhibitions, you’ve seen the scope of the show. And if you see both, you’ve expanded your understanding of the artist’s work.”

“Ascent” is the culmination of an ongoing Afrofuturism + Beyond program of exhibitions at RedLine, alongside The Black Power Tarot, also curated by McGowan. In The Black Power Tarot, an audience witnesses large-scale reinterpretations of the Major Arcana as imagined by King Khan and Michael Eaton, under the supervision of renowned tarot scholar Alejandro Jodorowsky.

At the Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities, Tunson’s work is shown alongside two other solo exhibitions curated by Director of Galleries Collin Parson: Anthony Garcia Sr.’s “Pigment,” and Lola Montejo’s “After Another After.”

“Because of how large our spaces are, it’s rare that we do solo exhibitions,” Parson said. "Doing three at once is something we've never done before. Garcia Sr. continues the historic legacy of Chicano artists in the region and co-founded an impactful nonprofit in his Globeville neighborhood,” Parson said, and “Montejo blends influences of her childhood in Spain with the New York School Abstract Expressionism that welcomed her to the United States of America as a teenager.”

“Overall, we allowed the physicality and limitations of our space and the scale of Tunson's work to dictate what pieces went where,” Parson said, referencing Tunson’s proclivity toward large-scale. Once the pieces were selected, Parson said, “we met at Floyd's studio with a brigade of people and box trucks to move the work. It was a full-tilt day of moving art up and down the three-story studio stairs in the heart of Manitou Springs.”

At the same time, Tunson’s large-scale “Hearts and Minds” — a 26’ by 13’ gift from the artist — is the centerpiece of a collaborative exhibit of the same name at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College, on display through July 9. The work was created over several years in the 1990s as part of Tunson’s Endangered series, a larger body of work addressing gun violence and “the endangerment of being in this society as a young Black male,” Floyd Tunson said in an interview with Rocky Mountain PBS. Colorado College and Colorado Springs School District 11 students reflected “Hearts and Minds” in studio work installed on adjacent museum walls.

Tunson “has unflinchingly explored his lived experience as a Black man in America since he first started showing his art over five decades ago,” McGowan said. “I’ve been fortunate to know Floyd and his art from the Colorado Springs and Manitou Springs arts communities since the late 1990s and early 2000s.”

McGowan, who is also Director of the University of Colorado — Colorado Springs Galleries of Contemporary Art, said she “gravitated toward Floyd’s assemblages and use of silkscreen printmaking and graphic elements from the first encounter.” McGowan’s standout curatorial partnership with Tunson includes the 2018 inaugural exhibit of the Ent Center for the Arts GOCA site, “Floyd D. Tunson: Janus.”

“I’ve been lucky to continue a relationship with certain artists. Working with Floyd will always be a top memory in my professional life,” McGowan said. She acknowledged her hope is that the “ambitious Ascent exhibitions” support drawing national attention to the artist’s career.

“Academic museums and nonprofit museums should be adding these works to their collections,” McGowan said. “It’s easy to make the case that Floyd is one of the most important and influential contemporary artists in the state and region.”

“He's just oozing with talent. He's always been driven, the way he is now,” Carol said. Through the years, Tunson studied at the University of Colorado, Parson’s School of Design, University of Denver, and Adams State College, where he earned his master's degree. Observing Tunson at work for 50 years, Carol said, “His frustration is there are only so many hours in a day.”

Carol, 81, met Tunson, 74, in 1971 when he was hired as the art instructor at Palmer High School.

As an English teacher in the same building, “I’d heard that there was this artist up there who had great work,” she said. “I went to his classroom one day, and he had some pieces of his as demonstrations for the students. What he was working on at that moment was so interesting — I had to just know more about it.”

Carol went to Tunson’s studio — and walked away with her first piece, a collage.

As Tunson pursued his own art in tandem with teaching, “he gave up sleep and eating regular meals and things like that,” Carol said. “Because he could not, not paint. He just couldn’t.”

“I taught in the daytime,” Tunson said. “I would go home, take a nap after school, and I'd wake up around seven. Then I'd go into my studio and work until sometimes one or two in the morning. Then I would wake up and go to school. I did that cycle for just about 30 years.”

“It’s wonderful to have inspiration, but art is mostly labor. It’s mostly hard work. It’s mostly discipline,” Tunson said. “I always tried to bring the best out of all students in their pursuit of the arts. Most of the studio practices that I was doing in school. I was also doing it myself,” he said, “so it helped tremendously that I was an artist that was teaching art.”

Still, “I tried to keep my art separate from the things that I taught in the classroom,” Tunson acknowledged. “I didn’t want to impose my personal artistic values on the students, or what art was for me. I didn’t want little Floyd Tunsons running around. I tried to give the students something more holistic that they could relate to.”

Many of the students he taught became “serious artists,” Carol said. “He saw their talent and gave them great encouragement.”

At some point, Carol said, she assisted Tunson in submitting artwork for a juried show, “and it kind of just went from there. I started doing a little more of this, a little more of that.” She inventoried, scheduled, and promoted. “It just became, I don't know — a habit,” she shrugged.

“When you work with Floyd, you’re also working with Wylene. They are a package together,” McGowan said, noting Tunson and Carol’s managerial relationship is “very uncommon, and very special.”

McGowan invited Carol to serve as co-curator with herself and Parson for the Denver program, noting “her contribution level is above and beyond.”

Carol’s managerial support “has made possible so much of Floyd’s prolific creation of work over time,” McGowan noted. “It made it so that he could have an active exhibition career and seek out representation.” (Tunson is represented by Denver’s Michael Warren Gallery.) It has allowed Tunson to establish and hold “effective boundaries around time to allow him to create work,” McGowan said, shielding him from mundane tasks and "that can really take up so much mental space.”

“I do whatever needs to be done,” Carol said. "It’s mostly dull, routine stuff,” she insists. Carol maintains pictorial and paper inventory of some 2,000 pieces, coordinates and plans with museums, and communicates with galleries and clients.

Carol writes copy for Tunson, saying she’s learned to “gather information from Floyd indirectly through conversations. Sometimes he doesn't even realize things he says are relevant to what I'm going to say about him later,” she said.

Without administrative support, artists can sometimes lose opportunities, Carol said. “These days, it takes multiple levels of support. I think for an artist, it really does take a village.”

While Tunson’s approach has remained unified over the last 45 years, “my understanding of it has improved — or evolved,” Carol said. Her role as Tunson’s manager enlivens life, she said warmly, in meeting fascinating people, attending events, engaging collaborative projects, and creating wonderful friendships — some, unanticipated.

Like one day, when a stranger called Carol up on the phone.

“I don't know how she found my phone number,” Carol said. “She said, ‘You don't know me, but I live across the street. And I've noticed that there's this painting on your wall. Would you mind flipping on your light? I thought I could see it again.’ I said, ‘Sure!’”

Carol invited the stranger up to take a closer look. They remain good friends to this day.

Carol gives an enthusiastic “Yes!” When asked if she’s always been a lover of visual art. "But — I didn't know it,” she adds. While attending high school in her small southern Missouri town, an observant teacher suggested she pick up a copy of the New Yorker.

“Well, I didn't know what that was,” Carol says. “So, I went to a shop and bought a copy.”

The magazine flipped a switch — one section in particular.

“I kept reading the art reviews,” Carol said in wonderment. “I didn't understand a word. I didn't know what it was all about. But I just kept reading these reviews.” Later in life, when she had an opportunity to see art, “I was just hooked,” Carol said.

As if on cue, the phone rings. “I have to take this,” Carol apologizes. It’s Parson, arranging delivery of the exhibition’s final pieces.

“I was at RedLine yesterday hanging boats, and one of the resident artists walked by and knew a lot about Floyd,” Parson told Carol over speaker phone. “And it turned out that Floyd was their teacher at Palmer High School!”

“No kidding!” Carol exclaimed, laughing. "Well, I’ll let Floyd know about that!”

Kate Perdoni is a multimedia journalist with Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.