Climate change and population growth creating conditions for more fires like the Marshall Fire

BOULDER, Colo. — The Marshall Fire, which devastated parts of Boulder County just as 2021 was coming to a close, is now considered the most destructive fire in Colorado’s history. Unlike 2020’s catastrophic wildfire season, which saw over 625,000 acres burned, the Marshall Fire burned just over 6,000 acres, but it destroyed more than 1,000 homes.

While fires aren’t unusual in Colorado, the Marshall Fire burned outside of the state’s typical wildfire season, which spans May through September. And according to experts, wildfires like the Marshall Fire are a continued risk in the Front Range as the climate continues to change.

As a fire expert and the director of Earth Lab at the University of Colorado Boulder, Jennifer Balch, who holds Ph.D.s in geology and forest ecology, understands what it takes to cause a fire like the Marshall Fire: a warm conducive climate, fuel and an ignition source.

“And we had all three of those coming into the end of December,” Balch explained.

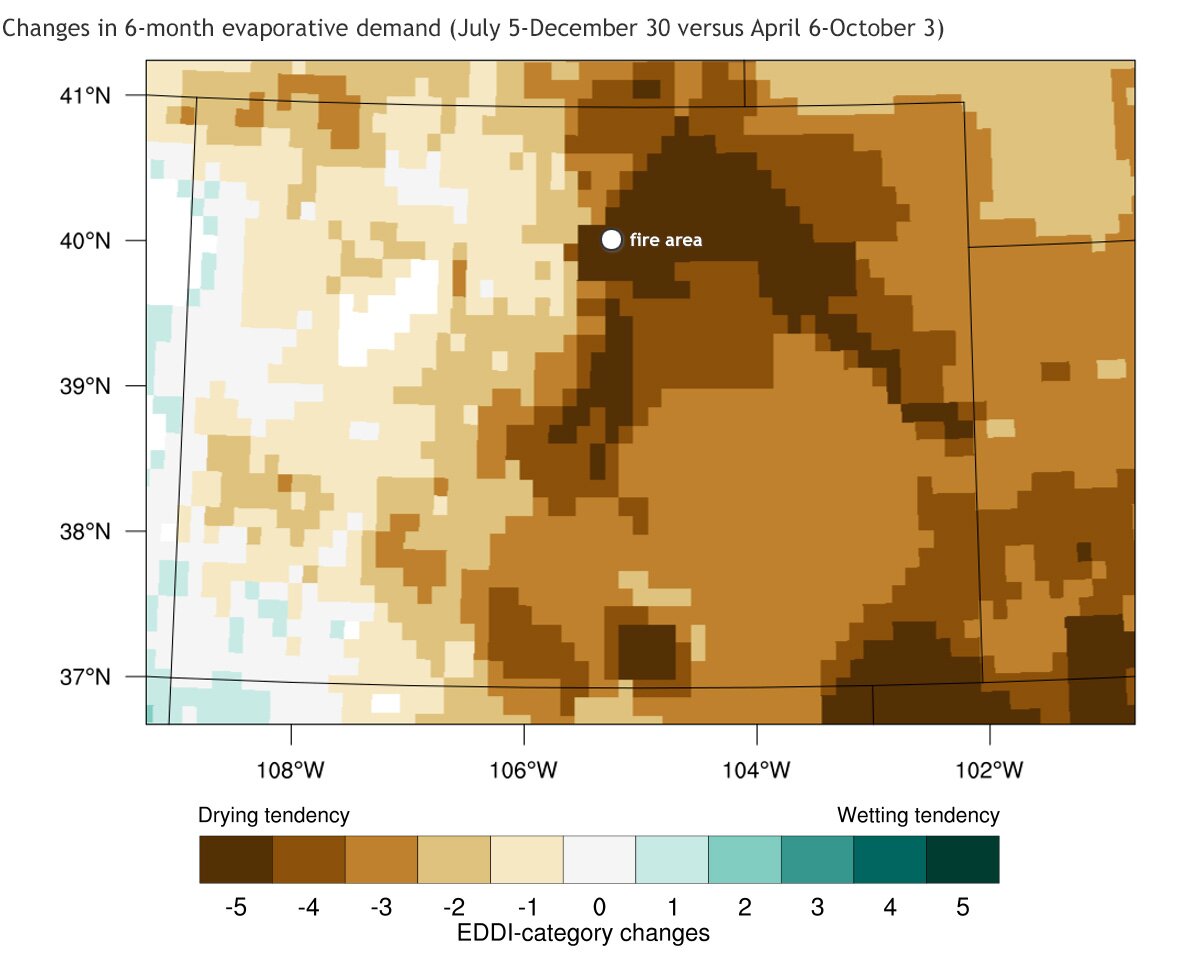

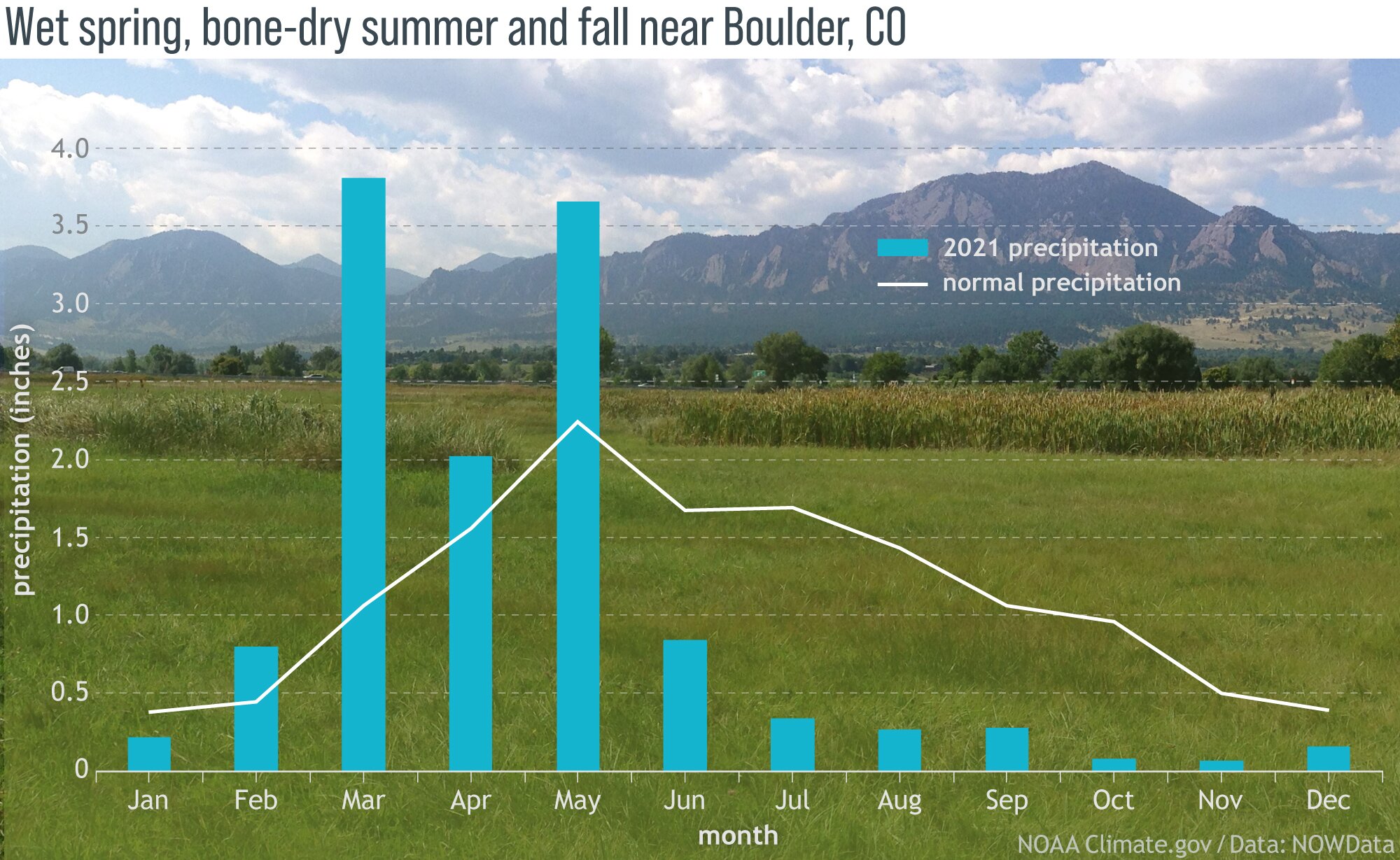

In December, Denver had its latest snow on record with just 0.3 inches on December 10. In addition, temperatures were 10 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit above average, with very dry conditions. The Marshall Fire started at the center of one of the driest areas in the state.

“It was the warmest June through December on record across the front range going back to the 1960s,” Balch added.

Fuel — anything that can burn, such as grass and dead leaves — was also abundant. A very wet spring yielded a lot of vegetation, and record-warm temperatures left the considerable growth dry and ready to burn. Balch pointed out that the grasses in the area at the time were very fine and “easy to ignite.”

“And we hadn’t gotten a lick of moisture as well,” she said. “So those two things made it prime conditions for fire to happen.”

The final element was an ignition source, which is still being investigated. But Balch said that ignitions during the winter are usually human-caused. "Ignitions in the middle of winter don’t happen naturally,” she explained. “We don’t have natural lightening ignitions happening at this time of the year.”

While these three components resulted in a fire, two other conditions in the area made the Marshall Fire significantly more destructive: high winds and home density.

The winds in the area during the time of the fire reached 100 mile-per-hour speeds, the equivalent of a Category Two hurricane. While high winds on the Front Range aren’t unusual, the hurricane-level winds accelerated the fire. In addition, the area where the Marshall Fire burned was already experiencing drought.

“And then on top of that, there was a lot in the way,” said Balch.

The Front Range has experienced massive growth in the past few decades and thousands of homes have been built between places like Denver and Boulder. Lined with fine dry grasses, these compact builds were “directly in the line of fire,” said Balch. Over 1,000 homes were destroyed as a result.

While the Marshall Fire isn’t even close to being in the top 50 largest fires in Colorado history in terms of acreage, it is now the most destructive, outranking the Black Forest Fire of 2013.

“It is also in the top 15 nationwide,” Balch pointed out.

Though it may appear that the conditions that merged to make the Marshall Fire so destructive are independent of each other, Balch said there is a noteworthy connection underlying the environmental conditions: climate change.

While research is still being done on the link between high winds and climate change, Balch said the connection between wildfires and climate change is clear.

“In the western U.S. we’ve seen that there’s been a doubling of forests that have burned since the 1980s, which is directly linked to how dry our fuels are as a function of climate change,” she explained.

There are significant portions of the year that have always been dry and flammable for Colorado — the “typical” wildfire season. But now, Balch said that season is becoming longer with climate change.

“We can now have fires that are in the fall, in the winter … talking about winter wildfires, that should be an oxymoron,” she said. Wildfire season is now year-round.

“We’re living with a certain amount of lock-in in terms of warming that we’re going to be living with over the next couple of decades because of greenhouse gas emissions that we’ve already pumped into the atmosphere,” Balch said.

Wildfire risk also increases where people build their homes. Balch and her team found that over the past two decades, over a million homes were within wildfire boundaries and about 59 million were within a kilometer of wildfires. As a result, Colorado has the third-highest number of properties that are at high-to-extreme risk of wildfire.

“What the Marshall Fire demonstrates for us is that, that risk has increased over the last couple of decades and it’s going to continue to because more and more people want to live in beautiful Colorado, but Colorado is also very flammable,” she said.

Balch's team also found that between 1992 and 2015, humans cause about 97% of wildfires in the wildland-urban interface (where buildings and other human developments meet vegetation), 85% of wildfires in “very-low density housing areas” and 59% of all wildfires wildlands.

As a fire expert, she knows that there are ways to mitigate this risk—and it all boils down to people. Building homes to survive flames, using controlled burns, and integrating wildfire education and awareness even in the suburbs can help mitigate risk.

[Related: Biden administration plans to increase controlled burns in Western states at risk for wildfires]

“Grasslands have always burned, shrublands have always burned, fires in forests have always happened, especially in Colorado,” Balch said. “But we’ve put a lot in harm’s way and the length of time during the year when we have to worry about it is now year-round.”

Clarissa Guy is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at clarissaguy@rmpbs.org.