Clothing donations make lifesaving difference for migrants facing first Colorado winter

DENVER — A low chatter and steady hum of music filled a room as people looked through piles of clothes and jackets. The late December crowd was not a rush of holiday shoppers, but rather migrants who had traveled thousands of miles for a chance at a better life.

Madeleine Prissela Maza Lopez looked for a pair of jeans for her husband, Reinel Javier Pérez Peña. For more than two weeks, he had been wearing the same pair underneath a pair of thin sweatpants to ward off the cold, only taking them off to wash them.

Maza also looked for warm clothes for herself and their 3-year-old daughter, Mariangeli.

“To provide at least something that to us may be something small it could mean the whole entire world — a jacket can mean literally from living to death out there in the cold weather,” said Carlos Herrera, project manager with Colorado Changemakers Collective, one of the nonprofits that distributes donations to migrants.

Related Stories

The family, who most recently lived in Colombia, said they arrived in the United States on Dec. 1 after spending four months traveling thousands of miles from South America.

They said they were detained in El Paso, Texas for a few days before getting a bus ticket to Denver. Pérez then said the Denver Department of Human Services gave them a plane ticket to New York, hoping that city, with more resources, would be able to care for them.

But after arriving at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York, the welcome center for migrants, officials there told Pérez and his family they didn’t have room for them, either. Officials in New York then bought them another ticket back to Denver.

Maza, Pérez and their daughter are among the more than 35,000 migrants who have arrived in Denver, a sanctuary city, within the last year.

[Related: New York City looks to amend ‘right to shelter’ rule as it struggles to house migrants]

According to Denver’s migrant dashboard, the recent wave of migrants is hitting an all-time high with occupancy reaching 4,495 sheltered in non-city facilities by Jan. 1. Since September, the dashboard shows there has been a steady increase in numbers, with a slight dip in November followed by a rapid increase in December when Denver reported 144 chartered buses arrived from Texas.

In total, Denver reports it has supported 35,980 migrants from the southern U.S. border since it started keeping track in early December 2022. The city also says all the support has cost more than $36 million so far. The State of Colorado awarded Denver a $3.5 million reimbursement and the federal government provided $1.6 million in advance with up to an additional $9 million available for reimbursement, likely to be collected as the city continues care for the migrant population.

In an appearance on “Meet the Press” Tuesday, Denver Mayor Mike Johnston said the city is at capacity for housing migrants and expects this will cost between $160 million and $180 million in next fiscal year’s budget to meet the need. Johnston said that figure accounts for almost 15% of the total city budget.

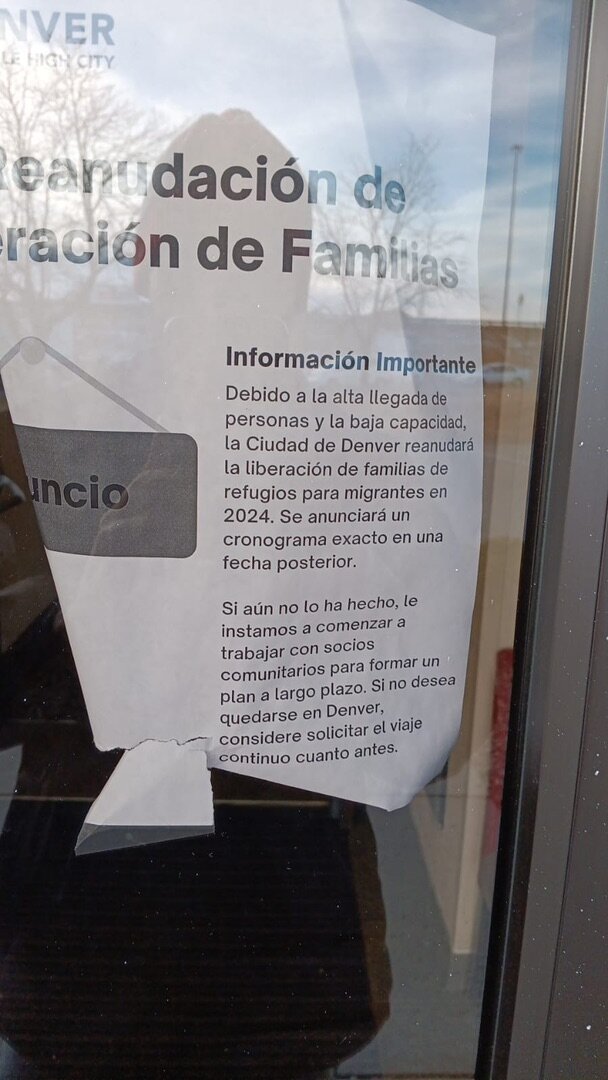

The City of Denver can shelter most of the recent arrivals but only temporarily — 14 days for individuals and 37 days for families, although the city suspended time limits for families on Nov. 17 because of the upcoming winter. But Denver Department of Human Services spokesperson Jon Ewing said the city will soon have to restart discharges because it just can’t afford to house the number of migrants needing help.

"With so many people in a shelter at this moment, there is just no way we can keep that going forever,” said Ewing.

He said the city has been trying to let migrants know that this change is coming but has not announced a date that discharges will start again. At the Comfort Inn shelter where his family stays, Pérez saw a posted flyer urging residents to find new accommodations and said he was told they had to leave by 11 a.m. on Jan. 20.

However, Ewing said the city has not yet determined a move-out date.

“There is a lot of misinformation out there,” he said.

With the time limits on the city’s shelters, scarcity of affordable housing and slow immigration processes, many of the migrants moved into tents within encampments around Denver. One large encampment near Zuni and 27th Street included hundreds of people and families. With a round of frigid weather moving in, the city announced Tuesday that it would open two additional shelters to move those living on the street inside. Officials said the city operates seven migrant shelters in total and also partners with the Archdiocese of Denver to provide bridge housing for families.

Denver city council members approved $330,000 of the budget to pay migrant’s first month of rent if they are employed and up to three months of rent if they're still looking for work. Ewing said they’ve had about 100 people receive leases through the program with another 400 applying for housing.

“The goal has never been the shelters,” said Ewing.

The shelters provide two meals per day for adults and three per day for children. Clothing, personal care items and additional assistance then fall to area nonprofits to fill the gap.

“We have been seeing that there's a lot of people that are having a big issue trying to resettle here in the United States because there's a lot of culture shock happening, a lot of trauma due to their long travels,” said Herrera.

Currently, Colorado Changemakers Collective is focusing on providing coats, warm clothes, hats, gloves, shoes and some personal hygiene products.

“They're coming here with basically nothing. They came from a very warm climate. This is a very harsh climate in comparison,” said Candice Marley, a Denver resident and executive director of budding nonprofit, All Souls Denver.

Marley and her group collected what she described as seven cars full to the brim with donations and gave them all to Colorado Changemakers Collective.

“I love this — how they do the timing — Like the families have an appointment, so [when] they come in, they can feel like they're actually shopping. They have a little more dignity than just like when they’re in the encampments,” said Marley.

On Saturday, Dec. 16, Herrera estimated about 350 people came to their office in the Montbello neighborhood to pick out the donations. The organization uses their promotoras, or community-based leaders, to get the word out when a distribution day will happen. Then the folks in need sign up for a time slot and “shop” for clothing items that are separated by type, gender and size.

Maza and her family filled up a large black trash bag with clothes they desperately needed. They are staying in the nearby Comfort Inn, which has been modified to serve as a shelter for migrants coming to the city, but only have a couple of weeks left in their stay. They hope to find work and affordable housing to provide a better life for their four children, though only one of them — their youngest — made the journey to the States with them.

Their journey to the U.S. started four months ago when they were living in Colombia. Maza is originally from Venezuela, which is in the middle of an economic crisis fueled by political unrest, hyperinflation and corruption that has spurred an exodus of thousands. But life for the family was too unaffordable in Colombia, where seven million people live in poverty, as well.

Pérez said they worked day and night for two weeks to save $50 for Maza’s father’s heart medication, a prescription he needed to refill every week. The pair could usually earn just eight or nine dollars for a day’s work. They also have three other children, who Pérez said often do not have three meals a day because of how bad the situation was for them in Colombia.

“Let's say that they do have breakfast, they don't have lunch. If they have lunch, they don't have dinner,” Pérez said in Spanish. "It's something critical. More than anything we did it for our children to come here for a better life.”

The family became desperate and made the hard decision to leave three of their kids behind while taking 3-year-old Mariangeli with them on the journey to the U.S.

The trek mostly consisted of walking from Colombia to the southern U.S. border through miles of dangerous situations.

The family began their journey by crossing the Darien Gap, a jungle between Colombia and Panama that has become a “highway” for migrants from all over the world. It is a three-to-six-day hike through mountainous, jungle terrain with cartels and thieves profiting from migrants all along the way.

Maza and Pérez and their daughter survived the Darien Gap but met with violence on the border of Costa Rica and Nicaragua. They said a cartel stopped them, robbed them and sexually assaulted Maza. The attack resulted in an infection for Maza that she treated with medicine she received from Doctors Without Borders in Honduras. The weight of what happened is something Maza and Pérez have been carrying with them ever since.

“Something happened to her along the way that sometimes I tell her that it is my fault for taking her with me. I had to come by myself first and then take her with me, but she decided to come with me,” said Pérez.

The brutality and hardships they experienced took a toll on Maza. She said she became severely depressed and attempted suicide. Still, their purpose carried them on.

To make more money, Maza and Pérez said they stopped in Guatemala for about a month to work and then made their way to Mexico. Then, while crossing that border, another cartel held them hostage and demanded anything of value or threatened to kidnap their daughter. To save her, Pérez said they traded their last prized possession — their phone — for Mariangeli.

After working in Mexico for another month, the family finally crossed the U.S. border near Piedras Negras, Mexico, about 150 miles southwest of San Antonio.

As they arrived at the U.S. border, the family said they turned themselves into immigration and despite paperwork from Doctors Without Borders, border patrol agents took Maza’s medication. According to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection website, only medications that can be legally prescribed in the United States may be imported for personal use. Even though they did not feel that was right, Pérez said they gave up the medication.

“I told her that it's hard, but that we should get rid of it because we were already here and what we came through to get our family ahead. They gave us a lot, they have helped us a lot along the way with money and here we are, thank God,” said Pérez.

Maza and Pérez now plan to stay in Colorado, no more moving. Still, there are challenges they face trying to make a life in Denver — finding a job and finding housing.

By Jan. 2, day 19 of the family’s stay in the shelter, Pérez said he was very worried about finding a job. While the city says it has not announced a date that discharges from shelters will start again, Pérez knows his and his family’s time there is limited.

“[I want] to help our family and stabilize myself, I hope our family is no longer worrying about the things they need now, such as saving her father and his medication,” said Perez.

“For our future [we want] to grow as people, learn a lot from you, learn a lot and I would say study your language, to grow in a job, to learn every day some job that God allows us to keep going,” he said.

Herrera with Colorado Changemakers Collective said Denver providing services for all the recent arrivals has not considered enough the traumas migrants have lived through on their journeys.

“They're very, very resilient individuals," Herrera said.

The collective expects to continue distribution days on the weekends when they can, depending on the availability and coordination with various other groups. As Herrera walked around the distribution room Saturday, he saw evidence that the Denver community cares.

“This is not just the organization doing it, but we cannot do it without the community. We have been seeing a lot of people in the different parts of the city taking care of those gaps as well,” he said.

If you’d like to donate clothing to Colorado Changemakers Collective, they ask that you call 720-385-9173.

Amanda Horvath is the managing producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. amandahorvath@rmpbs.org.

Alexis Kikoen is the executive producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. alexiskikoen@rmpbs.org.

Melanie Towler is the video editor at Rocky Mountain PBS. melanietowler@rmpbs.org.