'Cheap Land Colorado' author Ted Conover becomes an off-grid resident in his home state

COSTILLA COUNTY, Colo. — “This is the building of deadly varmints,” Ted Conover said with a tinge of humor, clicking a metal latch to swing open a wide wooden door. Once taken over by black widows — not to mention a rattlesnake encounter — the solar energy station in Conover’s backyard has gained a reputation.

“This shed was once filled with spiders,” Conover described, sweeping his hand above his head to illustrate how he’d unknowingly walked into a den of the poisonous desert arachnids. “But who knew it also had rattlesnakes?”

The author didn’t imagine he would wind up defending his own remote, five-acre plot from nature when he began researching the notoriously desolate Costilla County subdivisions east of the Rio Grande in 2017. Curious, and on assignment for Harper’s Magazine, he traveled to southern Colorado to interview remote prairie dwellers surviving beyond the energy grid.

“My sister told me she'd been to the San Luis Valley and seen a presentation about people living off-grid, on bare bones minimum,” Conover said. “People were parking their RVs on the prairie, and then adding a plywood addition, and getting water from a spring.”

Others live in old school buses, pallet homes, motor homes or shacks.

When winter comes, unable to survive the frigid negative temperatures in tents and campers, those who can afford gas often make their way to the nearest shelter, over an hour away in Alamosa, for a warm place to sleep.

“I had no idea people were really living like this in Colorado,” Conover said. “It made me feel a little bit ignorant, because I think this happens in several parts of the state.”

The remote, off-grid lifestyle on the flats of Costilla County.

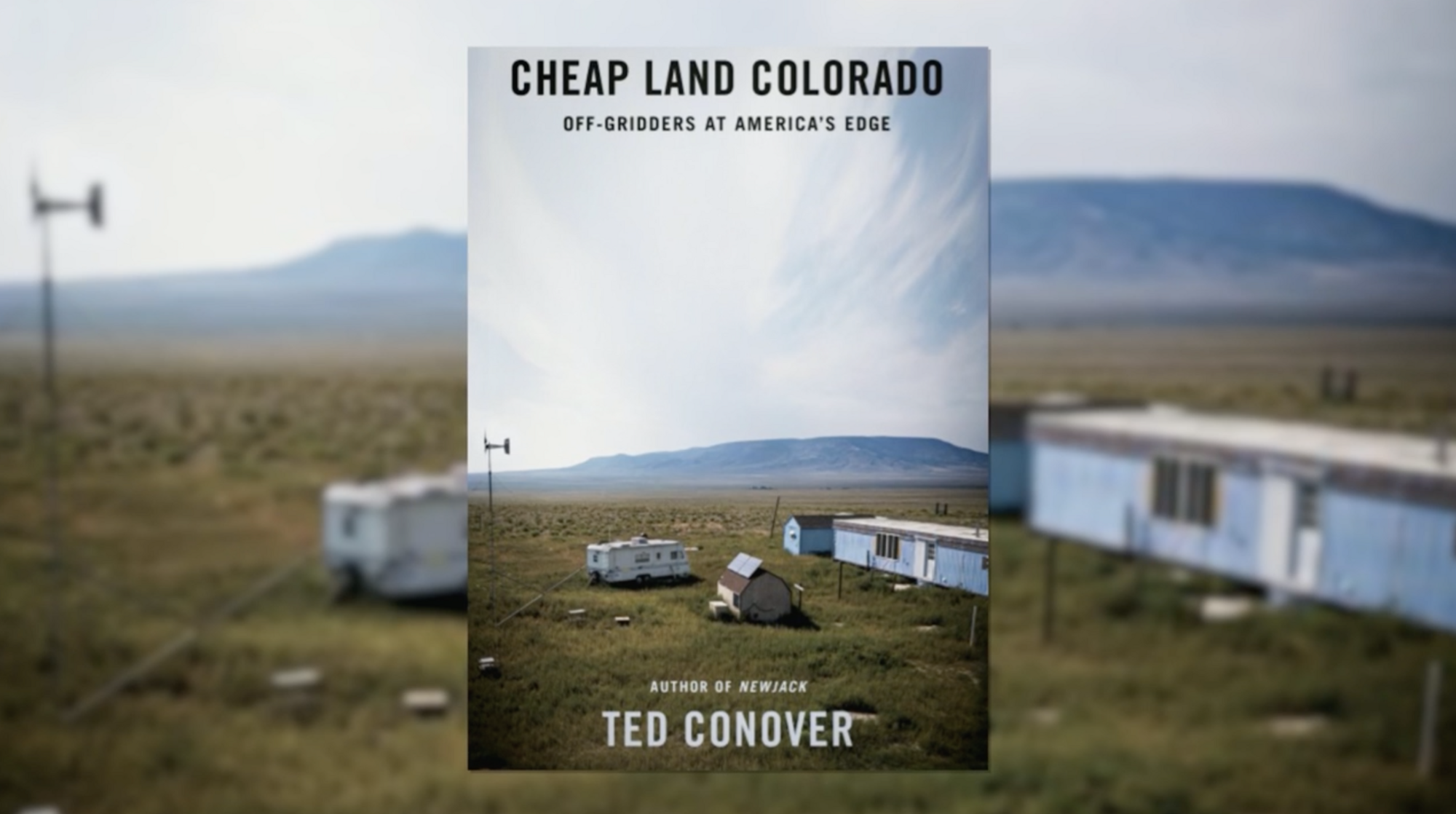

Intrigued by the rural prairie phenomenon, Conover visited the growing population of no-frills subdivision dwellers on and off for years to write “Cheap Land Colorado: Off-Gridders at America's Edge,” a book packed with a near suspension of disbelief around the harsh conditions of a dry, high, dusty, windy, beautiful, almost uninhabitable terrain and its people.

The book was published in November of 2022.

To get the full "cheap land" experience, Conover, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, purchased and moved a 25-foot trailer to a local family’s property and signed up to volunteer for La Puente, the rural homeless outreach shelter in Alamosa. The trucks of firewood he brought to prairie residents on behalf of La Puente became access points to novel characters and writing subjects — some of whom are now his neighbors.

"Cheap Land Colorado: Off-Gridders at America’s Edge," Penguin Random House 2022.

Out here on the prairie, “locals will tell you that where it really loses its luster is in the winter, when it's cold and gray, the wind is blowing, and it takes extra money to stay warm,” Conover said. “La Puente was responding to those needs when they started the program that I volunteered for. They were noticing all these people showing up at the shelter in Alamosa who were living out on the flats and suddenly got cold and had to come into town.”

La Puente “tried to prevent that kind of homelessness, which isn't what I ever thought of as homelessness before,” he said.

Author Ted Conover gives Rocky Mountain PBS a tour of his first home on the prairie, the 25’ camper trailer he lived in while working on his book, "Cheap Land Colorado."

Almost by accident, Conover became an off-grid resident in the community he came here to study, purchasing his own five-acre prairie subdivision plot in the middle of nowhere. He fell in love with the landscape and the locals, the “mostly serenity,” and a simpler approach to life.

By the time the autobiographical novel hit bookstores, Conover had settled into his own trailer and into a new rhythm. He has lived through his own storied stints on the wild desert terrain and returns every few months to the flats to inhabit the trailer pictured on the cover of his book.

A combination of volcanic rock and metal sheeting helps prevent mice from entering Conover’s prairie home. “This is the mouse-proofing that was done by a neighbor of mine,” Conover explained.

Conover at his new home on a five-acre subdivision plot in rural southern Colorado.

Raised in Denver, Conover returned to his home state to continue his career of immersion journalism. For decades, he has embedded himself in locales, situations and sub-cultures to document topics like train hopping, human migration and Sing Sing prison. (Conover worked as a corrections officer for nearly a year before he published "Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing.")

“The [San Luis] Valley has so much going on, and it's so different from my life in New York in ways that I wanted to know more about,” he reflected.

Conover’s desert home is a far cry from his place in New York City. Here, there are few neighbors and exceedingly long, sometimes impassable roads that disappear inside miles of sage and chamiso. This is a second home for Conover, who travels back and forth between his “other life,” as he calls it, as a journalism professor at NYU. But his neighbors know him only as the author who came home to roost. They have given him the nickname “Yankee,” and he is ceaselessly teased — a sure sign of acceptance.

The prairie flats.

Cheap land

In this part of the state, Conover said, lots for $5,000 or less can be found online by searching something like "Cheap Land Colorado," the title of his book.

“One of the great appeals for people is that you’re your own landlord,” Conover said. “The idea of owning your own land is a big deal. Even if it's cheap land, it means a lot to own your own land — and to be able to tell other people to get off it.”

While stereotypes persist — this is often considered by townspeople as a place of fringe lifestyles and firearms, distrust of government and county officials, and an off-skew, unpredictable population — Conover found all kinds of people trying to make a living here.

“It's a very strange mix. It's really not what you would expect,” he said. “There are people from all over.”

A road in the San Luis Valley Ranches subdivision.

Though there is no typical prairie resident, as Conover makes clear, most seem to want to be left alone. Conover admits he was naïve at first when driving down the long prairie driveways to offer firewood from La Puente. He quickly realized he was trying to meet face-to-face with people who did not really want to see anyone.

One person told him, “You know, you're either really brave or really dumb to be driving down a driveway like this.”

“And I said, ‘Probably really dumb,’” Conover remembers. “And there are outcasts of various kinds, people with warrants out for them, and convicted child molesters out here. They're a few lots away from the Christian family home schooling their kids. And there are people out here who everybody knows are involved in drugs, and often they're associated with things going missing from outside your place. And there are squatters. There are those aspects, for sure.”

Roadside advertising of today’s prairie subdivisions.

“The county has got a big burden from it,” Conover acknowledged. “There’s law enforcement, road maintenance and providing busses for education to get kids who live out here to schools.”

The county itself is a sore spot among residents, many of whom are quick to anger about what they say are unevenly enforced building and code regulations. Fees and requirements for things like fence building, well drilling and septic installation are bitter subjects. There is scorn for inspections, along with waves of enforcing camping violations. Though residents can camp for a certain amount of time, they can’t live in a tent. They can live in a camper if they are building for a while — but not forever.

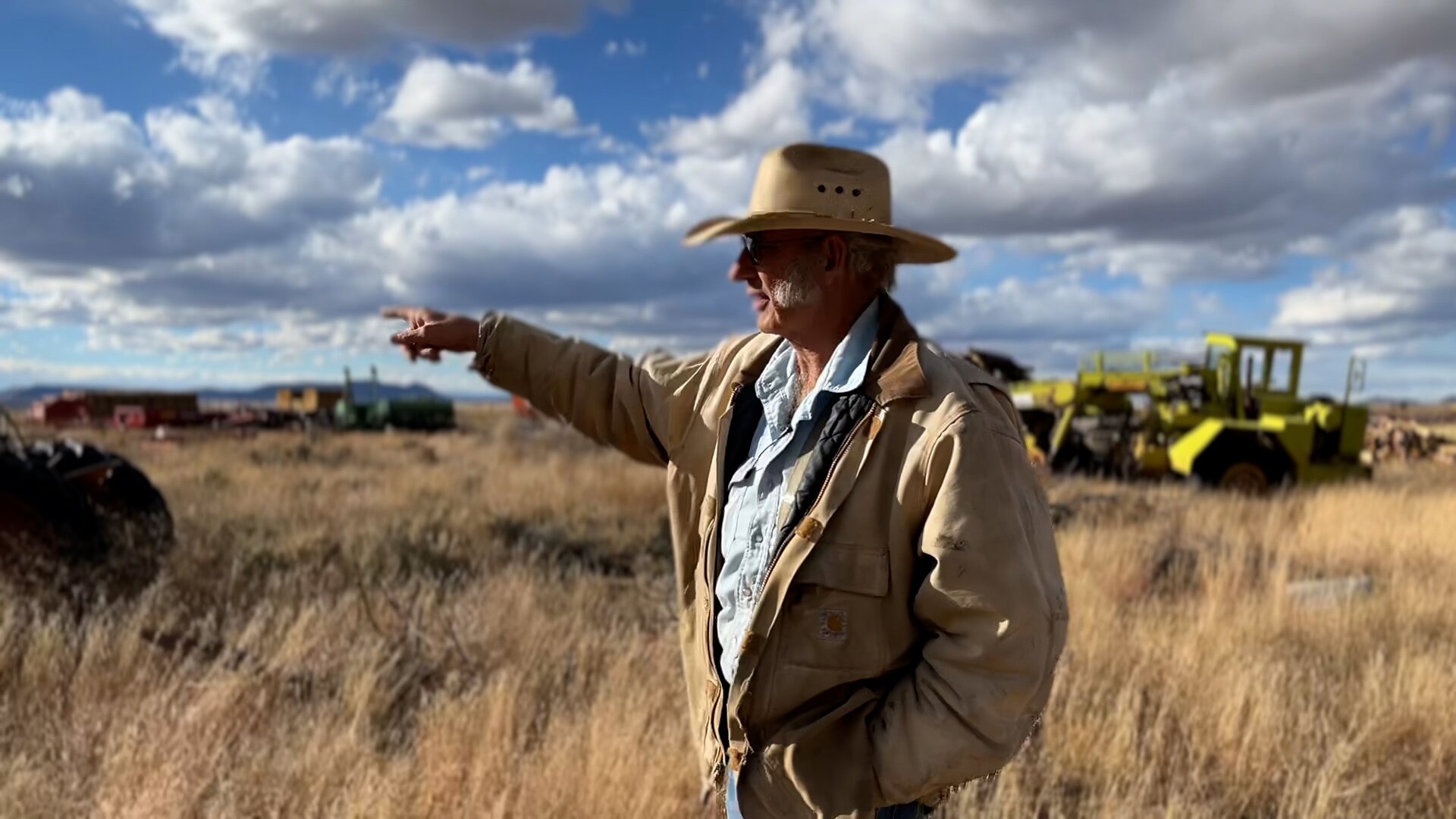

Meanwhile, Costilla County struggles to uphold building codes, emergency services and other amenities for the growing and isolated populations. There is strain between locals in surrounding towns and the prairie dwellers, said lifelong prairie resident Troy Zinn.

“However, enough different people are around now that people are getting more accustomed and more accepting,” Zinn said.

Still, “there’s a bit of animosity,” he added. “I really honestly thought the things had simmered down, until the outbreak of upheaval with the rezoning in 2016.”

When the county cracked down on non-permitted dwellings and septic permits, prairie residents flooded commissioner’s meetings to protest.

Zinn acknowledges some of the regulations were put in place after a rash of fires and deaths on the prairie associated with poor building practices.

“It’s understandable. People were coming out here and just throwing up a cardboard shack," Zinn said. "Any spark with a gust of wind, and it went up like a tinderbox. And if they got out, they were lucky to get out alive.”

A history of subdivisions

First Indigenous lands, then controlled by Spain, France, Mexico and finally the United States of America, this area was first created as subdivisions under the Costilla Estates in the late 1800s. As real estate, it has changed hands again and again, each time reinvented to meet a new type of settler. Similar marketing tactics — Mount Blanca in the background; no mention of the lack of amenities; advertising "lakeside properties" by drying reservoirs — have been deployed throughout history to entice people to purchase inexpensive rural plots.

From William Gilpin in the 1860s, to the television land swindles of the 1970s, subdividers have long relied on these advertising techniques. They sell a complete vision of the Wild West — now with the aid of the internet and its off-market resale sites, online marketplaces, Snapchat ads, and residents’ YouTube vlogs.

Over a century of inflated advertising has lured generations of farmers, ranchers and homesteaders here. Waves of settlers answered the call to make a go in the often-volatile desert landscape. With large-scale plans for irrigation, farming and ranching, elaborate canals and reservoirs were built dozens of miles west from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in the early 1900s. But water was overestimated and overallocated, and without it, plans for larger towns quickly went away.

An abandoned home on the San Luis Valley Ranches subdivision.

From cattle operations to grazing lands, the landscape has seen little evolution until the last decade. Today, more folks than ever are living in DIY shelters on unmarked plots “that are, to some degree, uninhabitable,” said Zinn. His family has watched homesteaders come and go for years — and lately, he’s seen more folks try to make a go of a life here.

Zinn’s family managed a cattle operation here during an era of agricultural subdivisions beginning in the 1970s. “Agriculture has always been pretty much ‘the’ element here,” Zinn said.

Troy Zinn was born in nearby Jaroso and has lived in Costilla County for most of his life.

Growing up, Zinn said, there weren’t any other kids on the prairie. His family went to Alamosa about once a month to do errands and stock up on groceries, which was an all-day affair.

“They would hide at the grocery store when they saw my mom coming,” he laughed.

Zinn went to school in San Luis. “One of about five white kids,” he noted. He left without graduating to pursue trucking and ranching. When times got tough, he would put his trucking equipment up for sale and drive for someone else for a while.

Back then, it was still quiet on the prairie. “It was subdivided out here, but there wasn't anyone out here yet,” Zinn said.

Today, “most of the smaller farming and ranching operations have gone away, and the big farms have moved in and taken over,” he explained. “I find it kind of sad, but it’s inevitable.”

Rich soil once grew “just about everything,” Zinn said, and now, tumbleweeds roll by. “You can have all the land in the world, but if you don't have water...” Zinn shrugged. Today, a bunkhouse, abandoned buildings and a mess hall remain of the old Banker’s Trust cattle operation.

Zinn laughed with a trademark chortle. “We’ve just gotten too broke to leave,” he said. “That’s pretty much the size of it.”

An old bunkhouse remains from the prime cattle ranching days.

“But I love it here. This is home to me,” Zinn said. “I like the quiet. It's not as quiet as it was when I grew up out here, that's for sure,” he added. A steady influx of people has “gone on for years,” Zinn said. “It's just gotten to be more and more every year.”

“Really only in the last 10 years, with the cost of living going up, and solar panels becoming affordable, did people use this land to actually live on,” Conover said. “New settlements tend to pop up over the summer, because that's when people arrive.”

Zinn said his wife calls it “neighbor season."

"People just start flocking out here like a bunch of disoriented turkeys."

Ted Conover tours the prairie subdivisions of Costilla County.

When winter comes, “Sometimes they'll leave their dwelling on it if it's a trailer, or they'll have started to build a house and they'll leave a foundation,” Conover said. “Sometimes they won't be back until the spring — and sometimes they'll never be back.”

“We’ve got quite a few that are committed enough that they’re actually putting down roots,” Zinn said. “Technology has really opened up a whole new field and a whole new opportunity for people to come out here in live and actually even work, with solar power or wind power.”

In the thick of sage and chamiso leading into the endless prairie, where most could not imagine taking up residence, few street signs remain. Cell service is limited. Folks often buy land without seeing it, and without realizing the lack of available infrastructure, Conover said. No water, no sewer, no gas.

“Out here, you’re also limited by the cost of travel,” Conover said. “Getting into town and back is a huge burden for a lot of people." Occasionally, someone will get a job in a nearby town — but employment is short lived when cars break down or gas gets too expensive.

Whether prairie or sage brush lands, many buy their property sight unseen.

Facebook and other social media groups are filled with would-be buyers wanting to verify rumors they’ve heard: Is there a chance for electricity? Can you drill for water? Just how cold does it get? And how hard, exactly, is it to live here? Many have seen land ads for Costilla County for years and finally saved enough to make the move.

Online users advise each other about county officials, a lack of local eateries, blocked and weathered roads, and Colorado’s state income tax. They urge fellow off-grid dreamers to read the fine print of their five-acre plot carefully — and to investigate permitting costs and availability of well drilling before purchasing their land.

Conover points out the Lobatos Bridge over the Rio Grande between Costilla and Conejos counties.

Jaroso resident Harold Anderson also sees his fair share of newbies trying to calibrate to the lay of the land. It’s not uncommon for someone to roll back and forth through Jaroso in search of their unmarked, recently purchased property.

On one occasion, Anderson said, a man showed Anderson a map of the property he thought he had purchased. “And he lays out this beautiful map on the trunk of his car. There was a grade school, a junior high, high school, a green belt, mini malls. I mean, I’d have bought a piece of ground, and I grew up here!” Anderson exclaimed.

None of those infrastructures exist.

Third-generation Jaroso farmer and rancher Harold Anderson.

[Related: Meet Harold Anderson, and learn about the Jaroso legacy]

Another first-time visitor, proud of the low-cost land he had purchased online, came through and asked Anderson about the price tag for getting amenities to his property.

“He said, ‘What's it going to cost to get power there?’ And I said, ‘You're looking at about three electric poles, meter, power.’ He didn’t think that was too bad. He asked about water, septic, all of it. I told him the cost. And he was cool until he asked me about natural gas, and I told him it was 25 miles away.”

“That's when he totally lost it,” Anderson said. “He didn't even go and look at his property.”

“People come in and buy it mostly because it's $99 down and $100 a month,” Anderson said. His own family traveled here in the 1910s to seek inexpensive farmland. “It was probably the same thing as back in the 10s and the 20s,” he said. “Here’s land, $1.25 an acre, where it's going to cost me $100 an acre in Iowa or Minnesota to buy a piece of ground. It's worth coming down for,” he said.

But distance, time and effort deter many from a second — or even a first — look, with many abandoned plots later sold by the county for back taxes.

The author, Ted Conover, at home.

“In the 1970s, you could come out here and reasonably imagine that this was all going to become a subdivision — a community of some kind,” Conover said. “And now in the 2020s, you can see if that's going to happen, it’s not going to be for a long time. There’s a dystopian aspect to this area that we're on, with roads that were built so that a realtor could sell a little five-acre plots of land, and that and so that the county could start collecting taxes on that land.”

With gravel roaring beneath his truck tires, Conover motions to either side of the overgrown road. “Indeed, the Federal Trade Commission came after the people who subdivided this land and made them offer refunds to anyone who wanted one,” Conover said.

When people leave the area, their homes are often taken down “a piece at a time,” Zinn said. Remnants of failed attempts to live here are left behind in the form of abandoned trailers, lopsided fences, and building debris. The local free press shows page after page of lots for sale for taxes. Half a dozen local real estate companies sell one to five-acre plots of land — though other real estate companies advise against it and refuse to engage.

“Some of these places have been here a long time, which you know by the trees,” Conover said, pointing across the sparsely dotted land. Since wells drilled by residents are meant only for domestic use — not lawns or gardens — trees are few and far between and take years to establish. Some residents forego a well, choosing to draw water from other sources or to purchase 500 gallons at a time from a town or traveling tank service.

For most people, including those with plans to grow marijuana when it was legalized in 2012, “it wasn't quite as easy as they thought it was going to be,” Zinn said. “A lot of them packed up and moved on elsewhere.”

“You still find some people who have a more romantic idea of being here and living,” Conover said, but he’s noticed that mentality usually only lasts a year or two.

Driving to visit his friends, the Grubers, who hosted Conover on their land as he drafted his book, he missed a turn and winded up buried deep in the crevices of the valley floor.

“You might wonder if this is even a road,” Conover said as his truck tumbled across the prairie. “Some of them get giant ant hills. Some of them get prairie dog colonies in the middle, and you'll see little heads popping up as you drive down. Rains wash out the roads all the time, and they get in really terrible shape. ”

“You have to look for very subtle signs,” he acknowledged, peering into his phone. Rain had replenished the burned-up grasses, following weeks of weeks of hot, dry winds and scorching days. Yellow flowers dotted the prairie, making the terrain even more difficult to decipher. A gravel road, created years ago, stood wildly overgrown with flowers.

Conover, unable to recover GPS directions, peered forward into the distance to determine a route.

“On the left is the Gruber's first homestead out here,” he said, pointing to the land where he once stationed his trailer. “And to the right of that, is the RV that they lived in before they bought the mobile home."

Before that, the family had lived in a trailer, and before that, when they’d first arrived, they had lived in a tent, he said.

Frank and Stacy Gruber hosted Conover at their prairie home while he drafted “Cheap Land Colorado.”

The Grubers themselves “adored having Ted” stay when he volunteered for La Puente, said Stacy Gruber. After Ted parked his trailer on their property, “the kids really enjoyed having him over. They got excited every time he came to town. And now, you know, it's confirmed,” Stacy said of Conover’s choice to purchase land here. “Ted can't leave us!” she laughed.

With stories ranging from frozen toothbrushes to the colorful language used by a pet bird the Grubers once rescued and kept, the family and Conover recalled his early days on the prairie with laughter and some disbelief.

“It’s really hard to actually live out here,” Conover acknowledged.

Yet he seems at home here, in this wind-filled, holy landscape that doesn’t magnetize everyone. The old-timers who have watched hundreds of prairie dwellers come and go are both impressed and amused by him.

Today, Conover traverses between the disparate realities of New York City and an un-pingable GPS coordinate somewhere just east of the Rio Grande and just north of the New Mexico border.

“I like both of my lives,” Conover reflected. “I love coming out here and how relaxing it usually is and all the space, and the low expense, and the different social world. I really like a lot of my neighbors.”

His wife, career and city lifestyle in New York present the opposite side of the coin.

“When I come back to Colorado, I notice things for the first time,” he said. “When you feel the wind blow and you feel the sunshine, you know you're experiencing a different kind of life.”

This article is part of a series. “Colorado Voices: Cheap Land Part I” is available on our YouTube channel. “Colorado Voices: Cheap Land Part II” airs Thursday, Feb. 16 at 7 p.m. on Rocky Mountain PBS and YouTube.

Kate Perdoni is a senior regional producer with Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.

Related Stories