First-hand air-quality awareness for residents in the most polluted zip code

This report is part of a Rocky Mountain PBS initiative concerning metro air quality. Watch Colorado Experience: The Most Polluted Zip Code (Part Two) here.

DENVER — Listening to the soft crackle of a song on vinyl inside her 1895 Victorian cottage, Ana Varela reflects on how lucky she feels to have found this home and this community three years ago. Despite some of the negatives she heard about the neighborhood, Varela said she felt right at home and knew Elyria-Swansea would become her “forever community.”

“I had people that were telling me, 'If you move north of Denver, you might be moving into a lower economic area, and there's going to be a lot of Hispanic people,'" said Varela. "I was actually really excited about that because I, myself, am Hispanic, and I wanted to be in a diverse area."

There's at least one thing Varela didn’t know about her new neighborhood: in 2017, ATTOM Data Solution ranked the 80216 zip code as the most polluted in the country. Dozens of industries including pet food processing, oil refinery, animal processing plants and more contribute to this distinction, as well as its location at the crux of two major interstates, I-70 and I-25.

[Related: How a Denver neighborhood became one of the most polluted zip codes in America]

“If you're ever in just total silence, you can always hear the cars. And recently, with the expansion of I-70, it's just more and more pollutants from construction in the area,” said Varela.

From 2018 to the summer of 2023, construction crews expanded a ten-mile stretch of I-70 from Brighton Boulevard in Denver to Chambers Road in Aurora. The section that divides Globeville and Elyria-Swansea was expanded from 85 feet to nearly 300 feet.

“We still always talk about the layer of dust that we had on everything during the expansion,” said Varela.

Learn more about the 80216 zip code

Many north Denver community members attempted to stop the expansion, filing at least four different lawsuits against the Environmental Protection Agency, Colorado Department of Transportation, and the City of Denver. They argued that the expansion would cut further into an underserved community and bring more cars, therefore more pollution to the area. All lawsuits were either dismissed, settled or ruled in favor of the defendants, allowing the project to continue.

“The biggest cause of air pollution from my experience with my research in Denver is the traffic,” said Shelly Miller, a mechanical engineering faculty member and air pollution expert at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Miller and several other researchers from computer science at CU Boulder and sociology at CU Denver worked on a project for the past two years to understand the environmental and social impacts surrounding the expansion of I-70, also known as the Central 70 project.

“This is the first time it's ever been done in Denver in this way,” Miller said about the project.

The Social Justice and Environmental Quality in Denver project is a multi-disciplinary study focusing on the communities of Globeville, Elyria-Swansea, Cole and Clayton. A social science team, a computer science team and an environmental engineering team were all part of the project. Miller also said the group conducted community outreach and partnered with several community organizations including Groundwork Denver, Green Latinos, the GES Coalition and more to conduct focus groups at the start of the project.

Shelly Miller, Ph.D. is one of the principal investigators of the Social Justice and Environmental Quality in Denver project. Photo: Alexis Kikoen, Rocky Mountain PBS.

“That has enabled us to really understand what the community members care about and what they need more support around and how we can better, better improve their understanding of what this project means,” said Miller.

The project supplied air quality monitors, developed and provided access to new mobile applications and distributed do-it-yourself air cleaners to participants. More than 120 people in the north Denver neighborhoods took part in the study from 2022-2023. The University of Colorado Boulder’s outreach grant program and the National Science Foundation Smart and Connected Communities program provided the funds for the study.

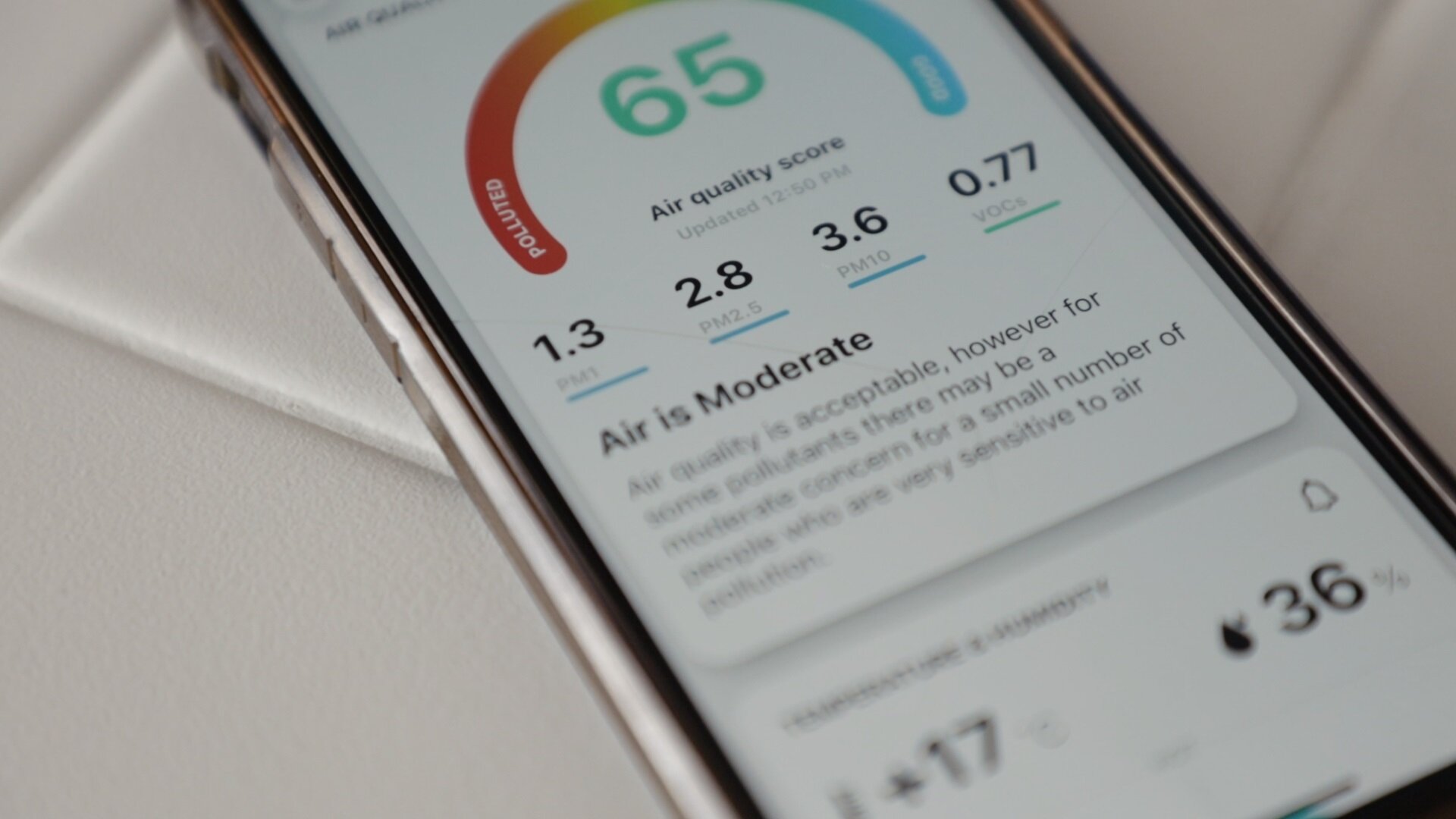

Varela works for one of the partnering organizations, GES Coalition, and participated in the study. Researchers gave her an air pollution monitor that she kept on or near herself every day for a month. During that time, Varela could connect to an app that would display the air quality data to her in real time.

“I really enjoyed that study because it really allowed me to see what is exactly happening around me in my neighborhood and not having to rely on another air monitor down the street,” said Varela.

The monitor measured personal exposure to several types of air pollution including particulate matter or PM, which is categorized by size of the particulate. Particles less than 2.5 microns in diameter or PM2.5 (which is significantly smaller than a strand of hair) are emitted from vehicle exhaust and industrial facilities and pose significant health risks. In 2019, PM2.5 exposure resulted in 1.8 million excess deaths.

Those in this Denver air quality study who had higher concentrations of particulate matter either cooked often without using an exhaust hood or opening windows, or they lived closer to I-70 and the construction. All information participants could see on their phones.

“They become air quality scientists, and then they're now armed with the data and the understanding of the data, and they can become advocates for their own communities,” said Miller of the study’s participants.

Participants received an air pollution monitor to carry around with them every day and an app to read real-time data. Photos: Alexis Kikoen, Rocky Mountain PBS.

Aside from the data, those in the study also received air cleaners made by the scientists. The air cleaners filtered out and reduced exposure to PM2.5 to make the participants’ lives healthier.

The study also examined the mental well-being of the participants as the Central 70 construction continued. This involved computer scientists with the University of Colorado Boulder.

“One of the main reasons for the need for this project was it was very well known that constructions like these are basically causing sadness in the community,” explained Shivakant Mishra, the lead computer scientist on the project. “However, there was no quantitative measure of these feelings.”

So, the computer science team developed an app that asked participants to take a short survey every day to indicate which emotions they were experiencing. Mishra and his team discovered that for those who lived closer to the construction, the level of happiness decreased.

“The other finding that we found was we saw that there was a real correlation between people's perception about their air and noise pollution around them and the level of happiness,” said Mishra. “We saw that the poorer the air quality or the noise pollution is, the less happy the people were.”

Shivakant Mishra, Ph.D., led the computer science team as part of the Social Justice and Environmental Quality in Denver project. Photo: Alexis Kikoen, Rocky Mountain PBS.

The computer science team also developed two other apps meant to intervene and mitigate the negative impacts from construction. One called, “Pure Nav”, provided personalized commute information to participants. Given the various road closures during construction of the Central 70 project, participants were often frustrated with the changing routes, so this app aimed to help.

Scientists developed another app after discovering the community felt a loss of belonging during construction due to I-70 splitting some of the neighborhoods. In response, developers created an app called “Pure Connect,” a localized social media app.

“They felt that their opinions, their concerns — they are not being heard by any agency, government agencies,” said Mishra.

Varela shared this feeling, saying her neighborhood is often overlooked, especially compared to wealthier parts of Denver. She said there are cracked and broken sidewalks, a lack of trees, no grocery, pharmacy or clothing stores nearby. Varela added that that many neighbors didn’t want and don’t use the park on top of the Central 70 expansion.

“My thoughts on the park over the freeway are that it is a perfect example of one community that isn't really heard,” Varela said. “The neighbors wanted green space, not Astroturf. The neighbors wanted access to active areas, not a locked gate.”

The Central 70 Cover Park includes a playground for Swansea Elementary, a turf soccer field and some other grassy areas. Some residents aren’t happy with the park above a highway full of cars. Photo: Jeremy Moore, Rocky Mountain PBS.

The park over I-70 sits between Columbine and Clayton Street and serves as the playground for Swansea Elementary. It features some spaces of with real grass and an artificial turf soccer field that has a chain and lock around it. Neighbors are also not keen to let their children play in a place that is on top of thousands of cars emitting fumes.

Issues like the park are what keep Varela and other community members fighting for a seat at the table and to be heard by decision makers. Still, she wishes this wasn’t the case for the place that she has come to know and love.

“Neighbors shouldn't have to work as hard and as full time as they do to fight for the basic things that other communities maybe take for granted,” said Varela. “It's imperative that we swing the pendulum the other way at some point. Otherwise, we will lose this community, the amazing history that comes with it and the people that are here.”

Amanda Horvath is the managing producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. amandahorvath@rmpbs.org.

Alexis Kikoen is the executive producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. alexiskikoen@rmpbs.org.