San Luis celebrates life of longtime human rights attorney

SAN LUIS, Colo. — The life of a human rights attorney who successfully argued three times before the Colorado Supreme Court to regain vital cultural rights for landowners in Costilla County was honored during a ceremony there September 26.

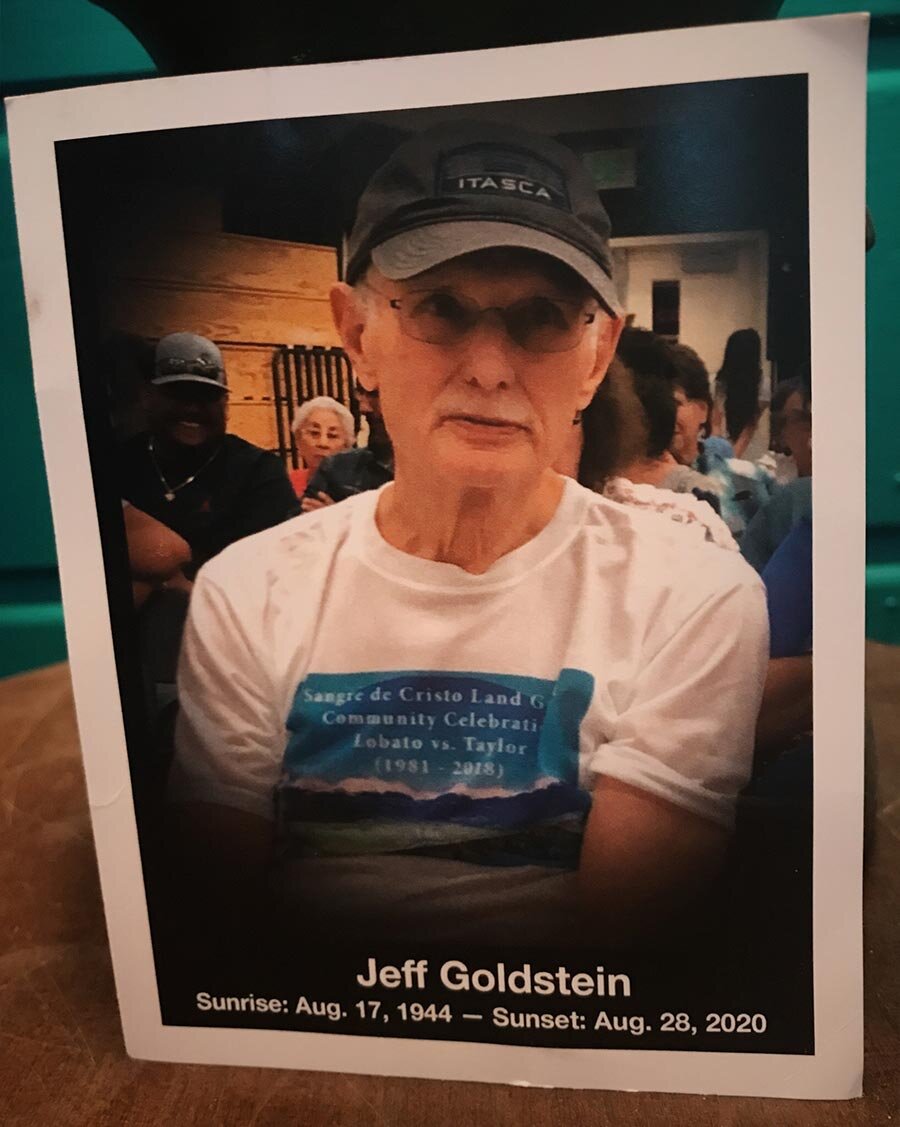

Jeff Goldstein passed away August 28, 2020 at the age of 76.

His life and work were remembered by plaintiffs, community members, supporters, and family in a memorial observance on La Vega, the historic communal grazing lands at the edge of San Luis, the oldest town in Colorado.

The Denver-based lawyer served Sangre de Cristo Land Grant heirs pro bono for 40 years as the lead attorney in Lobato v. Taylor, a historic battle against privatization.

Goldstein held that heirs could carry on traditional grazing, hunting, fishing, and timber rights on 77,000 acres of mountain land, including the 14,000-foot Culebra Peak, after the tract, known locally as La Sierra, was purchased and fenced off from the community. Record of historic cultural use paired with documentation of landowner settlement prior to the area becoming American territory led the Colorado Supreme Court in 2002 to restore some access, including limited grazing and collection of firewood.

The decision was recently upheld in Colorado Appellate Court in 2018 when a new landowner -- the fourth in the 16 years since the class action case triumphed in high court -- reawakened the issue.

Grupo Tlaloc of Denver opened the celebration of Goldstein’s life with a traditional Mexica/Azteca dance honoring the four cardinal points.

“We’re honored to be here to honor a very important man to this community, and all the work that he has done,” said Grupo Tlaloc director Carlos Casteñeda.

“This great man was truly, truly a lawyer of the people, which is something rare,” said Shirley Romero-Otero, heir to the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, plaintiff in Lobato v. Taylor, and co-founder and President of the Land Rights Council.

Goldstein was born in San Francisco, California, the eldest son of a dentistry professor. His grandparents on both sides were Jewish immigrants from Europe at the turn of the 20th Century. Goldstein grew up in West Los Angeles, graduating in 1966 from Valley State University and from the University of Southern California Law School in 1969. He moved to Denver in the early 1970s, where he lived until his death.

Goldstein was the founding member of the Worker’s Compensation Education Association, a claimant lawyer’s organization that educates and advocates for the rights of injured workers in Colorado. He worked toward legislative and administrative changes to better the plight of injured workers. During a career spanning five decades, Goldstein’s pro bono work was honored by the Trial Lawyers for Public Justice, the Denver and Colorado Bar Associations, the Colorado Hispanic Bar Association, the Colorado Lawyers Committee, and more.

A member of the National Lawyers Guild during the 1970s and 1980s, Goldstein and his partners represented a number of political activists, including members of the American Indian Movement, immigration rights activists, organizers in Denver’s Chicano movement, labor organizers, military servicemen who were against the Vietnam War, and victims of police brutality.

“He was always involved with those who were doing ‘good trouble,’" said Land Rights Council Secretary and Treasurer Juanita Martinez.

Stemming from this work, Goldstein launched his decades-long representation of the heirs and descendants of the original Hispanic settlers on the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant.

Spanish conquerors overtook indigenous populations in the region over the course of hundreds of years, then lost claim to the area to Mexico following the Mexican War of Independence from the Spanish Empire in 1821.

The Sangre de Cristo Land Grant was formed in 1843 by Canadian fur trader Charles Beaubien, who moved through America and into territory occupied by Mexico, where he became a Mexican citizen. After petitioning the Mexican government for land, he came to possess nearly 3 million acres of what is now southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. He invited settlers to the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, offering newcomers the right to utilize the mountain tract for sustenance.

The Sangre de Cristo Land Grant was affirmed within the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, an agreement between Mexico and America that effectively ended the Mexican-American War in 1848. The Treaty ensured the upholding of existing property rights of those Mexican citizens now living in the newly American-transferred territories.

Mexicanos who had previously settled land under Beaubien had the choice of relocating to within the new territorial boundary of Mexico, or remaining to obtain American civil rights and citizenship in America.

For those who stayed, a unique culture continued, dependent on sustenance agriculture and continued stewardship of resources from the same mountain land that had drawn their fore families to settle there.

Generations of locals enjoyed rights to the land until the 1960s, when lumber baron Jack Taylor purchased the property, then won a federal court case barring local landowners and residents from exercising their historic rights.

Representing plaintiffs organized by the Land Rights Council in San Luis, Goldstein filed a class action lawsuit in 1981 against Taylor to restore traditional access to hunt, fish, graze cattle and other livestock, and collect firewood and timber for construction of adobe homes.

A large team of pro bono lawyers headed by Goldstein took the petition through dozens of lower district and appellate courts before successfully winning the right to take the case to trial. Though both the trial court and the court of appeals held that landowners had no legally enforceable rights, the Supreme Court reversed these decisions after successful arguments by Goldstein in 1994, 2002, and 2003.

In 2005, more than 350 families received the first keys to once again access the Land Grant.

“Implementation of those decisions has required further litigation that continues to this day,” said Martinez.

The case garnered national and international recognition, and is seen as a tremendous victory for the people and traditions of the San Luis Valley. The epic struggle to preserve a cultural lifestyle underscored years of need in San Luis and its surrounding Culebra Watershed villages that rely on the mountain for the provision of natural resources.

“Countless generations of families who will use their land grant rights will be forever grateful to Jeff for leading and winning this classic David vs Goliath battle,” said Martinez.

Over 1,000 individuals now have access to La Sierra, Romero-Otero said. "This summer, over 300 individuals have used La Sierra to graze animals, gather firewood, and utilize lumber for construction," she said. “And all of that we owe to Jeff Goldstein and the 48 other attorneys that have worked with us from 1981 to this very day.”

Eight new attorneys, Romero-Otero said, came on board this summer.

“Jeff worked diligently, tirelessly, and without ever taking anything from the community," said Romero-Otero.

“Jeff did so much for us. He stuck with us, and he never charged us a penny,” said Jose Martinez, Land Rights Council Board Member. “We could never repay all he has done for us.”

“When Jeff took this case on, he did so not knowing how long and intense the struggle was going to be," said Romero-Otero. “We thank Jeff and all of the attorneys for sticking with the community, for believing in our cause, and for giving us access to the much needed Sierra that we need in order to be able to survive in this beautiful community.”

Jose Martinez said he had the privilege of traversing the mountains in his youth. “There are beautiful canyons, meadows, rivers, and forests,” he says. “It is all part of La Sierra. The mountain has given us everything that we have; it is the sustenance of this community.”

Pete Espinosa, one of the nine named plaintiffs and the first to get a key to regain access, said Goldstein helped his community during a “hell of a struggle.” Espinosa said he could not believe it when he returned home from serving in the Vietnam War only to find that he could no longer access the land he was raised on.

“The first thing we ran into was ‘No Trespassing’ signs,” he says. “We had to fight.”

Espinosa referenced threats, beatings, and violence against his family and community from the landowner as they sought to gain access.

“Outsiders have no concept of the bloodshed that ran on the dirt and in the mountain,” said Espinosa.

Espinosa spoke of courtrooms filled with disrespect and discrimination, overturned decisions, an arduous series of trials, and a battle beginning in his youth that is still ongoing.

“We’ve all aged,” said Romero-Otero. “When I started, I was 20. I just turned 65. It gives you a scope for how long some of us have been involved.”

“Forty years is a long, long, long time -- especially on a pro bono case,” said Jerome DeHerrera, one of two lead attorneys on the present-day case. “When Jeff took this case on in 1979, it was a prayer and a dream. The rights were already extinguished. Jeff saw this case all the way through. That’s amazing and remarkable."

San Acacio resident and heir Roque Madrid said, “I met Jeff before the Land Rights Council existed. He was my attorney for a mess that I got into in Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1973. He came to me instead of me going to him. Jeff was not only an attorney; more important than anything, he was my friend.”

As plaintiffs and community members spoke of their appreciation for Goldstein, they also thanked his family for their years of service to the cause.

“With Jeff also came his wife Marcia,” said Romero-Otero. “We really got the entire family of support. Jeff became not only our colleague, but also a very close and dear friend. He really got to know the people in this community throughout the four decades he worked here.”

“Jeff was thinking about the case all the way until the end,” fellow attorney DeHerrera said. “This community is extremely blessed to have Jeff, and the fortitude he had for forty years to see it through to the very end.”

As plaintiffs return to the courts to defend their rights each time La Sierra changes ownership, DeHerrera said his team will be on the case for as long as it takes.

“Long live the fight for this case,” said DeHerrera. “Hopefully it won’t be that much longer… but it probably will.”

"This is a story with many chapters," said DeHerrera. "This is not the last chapter.”