Traveling Colorado’s oldest water system

This report is part of a series from within the Río Culebra Watershed. Read parts one and three.

COSTILLA COUNTY, Colo. — When I arrive three minutes late to Charlie Quintana’s farm west of San Luis via a long stretch of chamiso-filled highway, Quintana is at the end of his driveway, waiting to make the turn out to his fields. I jokingly ask, shouting over the engine, if he was going to leave without me. I realize he was.

To learn from Quintana is a special opportunity. He spent almost three decades managing the local acequia irrigation system – the oldest water rights in what is now Colorado, created within a Mexican Land Grant and predating statehood by 24 years. Today, Quintana has agreed to travel his old route across the Río Culebra Watershed to give me a tour.

But first, there are chores. We hop in his field truck, head out to the flat of the lands, and spend an hour moving tarp dams and siphons left from flood irrigating off the acequia. As he fills the pickup bed with various tools, Quintana jests that I can unload the truck when we get back, and regales me with stories from his lifetime in the watershed.

In the Río Culebra Villages of arid, desert southern Colorado, el agua es vida: Water is life.

The crux of ranching and farming is snowmelt and any supplemental rain. Natural waterways wind from the canyons through the desert terrain. The acequia system taps into these creeks and streams with a series of earthen and concrete-lined ditches that bring water to fields. Dug by settlers in the mid-1800s, acequias are physically cleaned, repaired and maintained by water rights holders. Today, many of those people are descendants of area settlers.

As the state-appointed water commissioner, Quintana traversed the Río Culebra Watershed daily to administer acequia water rights.

“My realm was north of San Luis from the Rito Seco all the way south to the New Mexico state line,” recalls Quintana, "and from the middle of the mountain peaks, which flow west, all the way to the Río Grande."

Above in the Sangre de Cristos, forests of aspen and coniferous trees protect waters, their shade allowing for a more gradual runoff.

Quintana points at the mountain peaks, naming each canyon. “Our main water source is right there,” he says.

These creeks and streams are at first nothing more than small pools and springs that gather and join, weaving down with gravity. Downstream diversions allow for water to be gated out to individual branches of the acequia system.

Today, an estimated 73 ditch systems serve around 300 families who grow crops including hay, alfalfa, corn, peas, potatoes, and beans, many with traditional flood irrigation. Some farmers use thick plastic gated pipes to divert water from their acequia onto their fields.

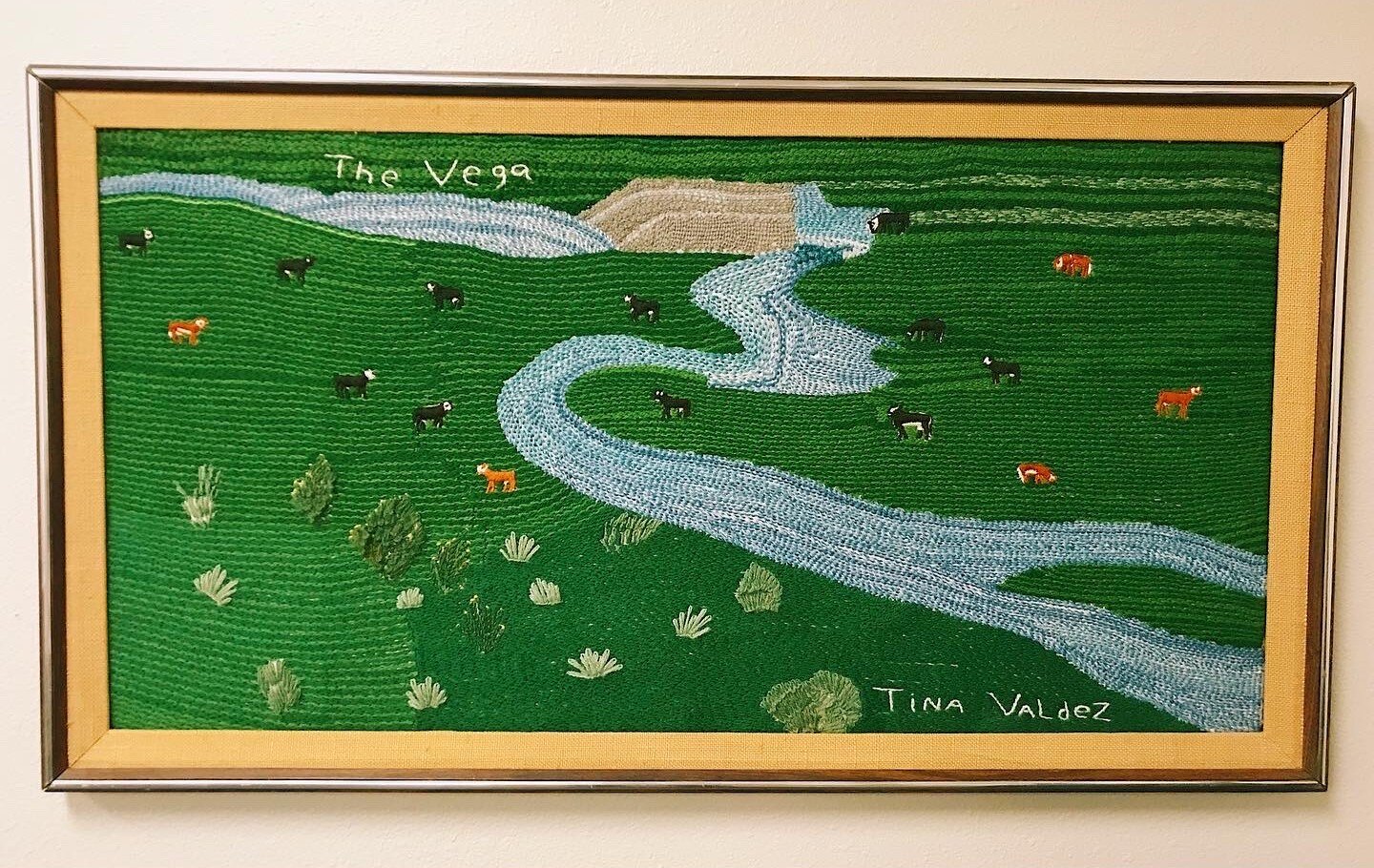

Quintana’s water right originates from the Río Culebra, winding like its namesake snake through the land, coursing through the Vega Commons before heading west toward the Río Grande.

Unlike the acequias of neighboring Conejos County, this Watershed does not contribute to the Río Grande Compact, an interstate agreement allocating waters downstream to New Mexico and Texas. Exclusion from the Compact is a saving grace – especially now, said present-day Water Commissioner Tom Stewart.

“This year on the Conejos system, we curtailed down to 25% of the number one water right on the system,” he said. “Part of it was because of the Río Grande Compact. As Water Commissioner, you’re dealing with terrible, terrible stresses on people who are trying to make a living out of water.”

Colorado’s water is famously over-appropriated, “and has been for 120 years,” said Stewart. In the San Luis Valley, emergent groundwater models reflect the health and sustainability of interconnected water supplies, revealing, for example, the effect of aquifer pumping on other water rights. Center pivot sprinklers drawing from groundwater supplies are now closely monitored. Sub-districts have been put in place to both pro and re-actively engage in a balance of water supply and consumption.

“We're in a very over-appropriated system, not only with surface water, but also groundwater,” said Craig Cotten, Division Engineer for Division 3 of the Colorado Division of Water Resources. “We actually haven't allowed new wells that are for irrigation in the San Luis Valley since 1982 and in most areas of the Valley, since 1971.”

“So it has been 50 years since we've allowed bigger, commercial irrigation wells. Because even back then, we realized we didn't have enough water to go around,” Cotten said.

“Back east, where there’s plenty of water, they use the Riparian Doctrine,” explained Cotten. “Generally, if you’ve got water on your land, you can take it for your purposes.”

Water rights in Colorado and the West are instead determined by a priority system.

“Here in the West, we have not enough water,” Cotten said. “We developed the Prior Appropriation Doctrine, which basically says that if you're the first person to put a ditch in on a stream system, then you can take water first in times of shortage.”

Mining claims and sluice boxes prompted the need to create a system of order for water use in the state, Cotten said.

Constructed starting in the 1850s before any other water system in what is now Colorado, the acequia system holds the earliest water rights, or first priorities.

“How the priority system came around, I don't know,” Quintana said. “I'm not a lawyer or anything. Pero, in my mind, I figure this way: San Luis first appropriated water from the Creek. They made the San Luis People's Ditch. What for? For their gardens and trees and animals.”

“But — it wasn't adjudicated,” said Quintana. “Adjudication means you make it legal through the courts.”

Settlers whose presence predated the United States of America were called to testify with evidence about the history of their water use.

“They had objections, and a whole trial to figure out which acequia was first, second, and on down the line,” said Cotten.

The District Judge ruled on the order of prior appropriations and an administration list was created.

“The San Luis People’s Ditch became the first priority — and on and on,” said Quintana.

“The acequia system is the priority system,” said Quintana. “One, two, three, four, five.”

As each acequia reaches their decree, the next priority is allowed use. When all the available water has been allocated on any given stream system, the system is shut down in reverse.

“If there's a shortage — which there almost always is — the more junior ditches might only get water for a week or two, or maybe a month, during the high part of the season during the runoff,” said Cotten. “Whereas the senior ditches are getting water almost every single day of the irrigation season, if they want it.”

Two decades of drought overlay the task at hand. Lack of snow melt or rain affect hay production, livestock, landscape, economy — virtually every aspect of life.

“It’s too bad water is not limitless,” said Stewart. “Scarcity is the big issue. The people in these small communities feel it every day.”

“These are tough times,” he said.

“‘Oh,’ you say, ‘I'm from Washington state. We didn't have to worry about water!’ Over here you do. This is arid. This is a desert,” said Quintana.

In 26 years as Water Commissioner, it’s fair to say Quintana saw it all: cut locks, tampered head gates, smashed water measuring devices, and a few very angry people.

In one instance, he was approached by an acequia user while standing in the ditch.

“She was irate,” he said. “I mean, irate. I decided I would stay in the ditch until she calmed down, because if I got out – she was going to throw me back in.”

In another case, a wooden metering station was replaced with a steel one because “they, uh, broke the wooden one,” Quintana said.

Like, on purpose? I ask.

“Like on purpose,” Charlie affirms. “Like, really on purpose.”

Another time, a water rights holder, “plus their lawyer, plus the sheriff, and a whole bunch of people behind them,” appeared at a head gate to dispute an amount of water, Quintana said.

“That was the hardest day of my career,” he said. “I just had to lock the gate, get in my pickup and leave.”

Mostly, though, he said, people get along.

“If you know how to talk with people, you’re going to be okay,” he said. “You’ve got to learn a lot to be able to take care of the whole system,” he acknowledged.

“I believe you have to live it for a while to really understand it,” agreed Stewart, who grew up west of here across the Río Grande in Conejos County. His great-grandfather helped dig the William Stewart Ditch for the family property “by hand, and with horses,” said Stewart.

“There’s not much science to it, because we do what a Judge tells us to by a decree,” said Stewart. “But the skills of being able to work with people, I believe, are more important.”

Cotten said the Division of Water Resources strives to hire local Water Commissioners who have personal, on-the-ground knowledge of the system.

And, yes: those with excellent interpersonal skills are at the top of the list.

“It’s a unique job, said Cotten. “If you have to call someone and say, ‘Sorry, you need to shut your ditch down,’ they’re not always happy. It really takes a good person, with good people skills, to be Water Commissioner.”

When communication falters between water users, the consequences can be dire.

“You think your neighbor is taking your water, and he isn’t — but in your mind, he is,” Quintana said. “And if there’s nobody to tell you that he’s not — after awhile, he gets hit by a shovel.”

“There [are] water fights,” affirmed local acequia user Arnie Valdez. Long ago, on his acequia, “two guys got into a fight, and one guy killed the other guy with a shovel. He just sort of left him on the fence. Kind of like a message: ‘This is what happens when you steal water,’” Valdez said.

On this vibrant fall day showcasing the beauty of the Watershed, Quintana glides his truck from the mountain’s gate down through rural gravel roads. We visit nearly every diversion point, peering into willows and seeking out high water lines.

In many cases, when the earthen system was updated with concrete and steel diversions throughout the early and mid-1900s, the structures were engineered for a great deal more water coming through.

Sanchez Reservoir, created 1907-1912 to accommodate water rights claims for newer agricultural settlements west of the Watershed, today is historically low.

The acequia system is revealed – even from a distance – by lines across the land of trees, brush, willows, and tall grasses springing to life. It is a habitat that has been nurtured – and has nurtured these communities – for almost 200 years.

We gently sink in elevation as we trade rattlesnake encounter stories — Quintana’s is way funnier — and I point out the red hawks keeping tabs on us from high in the trees.

We head home toward Viejo San Acacio, the chamiso landscape transformed into fields of bright yellow flowers from the rain against the backdrop of Sisnaajini, the Navajo sacred mountain of the East.

“This is heaven for us,” Quintana said. “It’s beautiful.”

Kate Perdoni is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.

This report, the second in a three-part series within the Río Culebra Watershed, was conducted through a fellowship with the Gates Family Foundation, Rose Foundation, and Rocky Mountain PBS.