Fall on the Río Culebra: Lifelong rancher reflects on life in the watershed

COSTILLA COUNTY, Colo. — It is fall on the Culebra River. Hay bales are going up into stacks. Cows are coming down from the pastures. Some cattle stand, staring as we pass the gate, their noses pressed between the metal rungs — forlorn harbingers sensing of incoming weather.

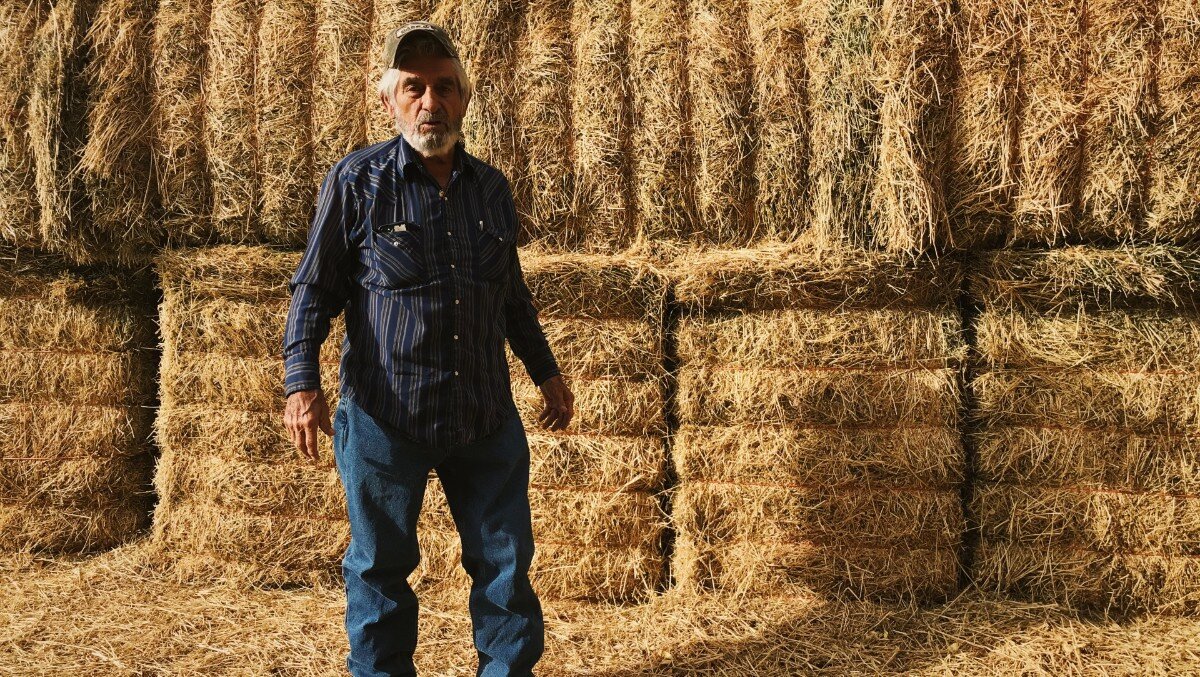

“They can tell it’s time to come home,” remarks Charlie Quintana, 77, a lifelong farmer and rancher, from behind the pickup steering wheel. My camera gear and I take an involuntary, miniature leap each time we hit a bump in the field. To the east through the pickup window, as far as the eye can see, stretch the Sangre de Cristo mountains.

“I don’t know how they know, but they do,” he says of the animals’ impulse to return.

There’s a word describing homing instinct in the Spanish language—querencia—the intrinsic desire to come back to a safe place, the habitat from where your strength and character are remembered and drawn. Perhaps Quintana’s cows studied linguistics; the term is not just applicable to people. In bullfighting, querencia is the place in the arena where a bull feels strongest. A conceptual space, it’s developed over the match, providing the bull psychological gains as it revisits throughout.

Querencia is often a topic of conversation. When folks return after an absence, or rue in social media groups about their longing to return, there is querencia.

This love of a sense of place has been honed and handed down by descendants of Spanish and Mexican settlers for almost two centuries. It is woven into a local Indigenous heritage that dates back thousands of years.

Jicarilla Apache, Ute, Navajo, and other Native American tribes traveled and lived in the region for an estimated 2,000 years before colonizing forces encroached. Prior to that, Native American Paleo-Indian cultures were present for an estimated 11,000 to 14,000 years. Tribes and Indigenous cultures of what is now the American Southwest were subject to the documented inhumanity of Spanish conquistadors, followed by hundreds of years of brutalized war, enslavement and captivity, and forcible relocation by invading nations.

Remaining First Peoples were sequestered to reservations beginning in the 1850s, forced to walk the duration of their migrations. A complex result of identity and politics remains.

“We’ve got Indian blood, Mexican blood, Spanish blood — you name it, we got it,” said Quintana, turning the truck from the dirt access path of the field onto a gravel road.

This cultural crossroads is evident in ongoing traditions and customs of the region, from religion and spirituality to craftsmanship, skills and talents that have been sharpened for generations.

Even natural resource management and the local system of water delivery reverberate world conquest and migration. Communally-held irrigation ditches, or acequias, use methods traced back to Romans and Moors who occupied Spain. The Spanish brought these desert irrigation techniques to what is now North America, melding with pre-existing systems of the Pueblos in what is now New Mexico.

These lineages came north to what is now the San Luis Valley in the mid-1800s, mirroring the settlement of the Taos Valley to create some of the northernmost villages of what was then Mexico.

The watershed’s fertile creeks and streams along with nearby mountains provided all the resources for settlement. Each village along the Río Culebra took on the name of a patron saint, often in accordance with the natural world. The homages serve as prayers, honoring nature and ecology for survival. The livelihood of local farms and ranches depends on the amount of snowmelt each year in the mountains above.

“If we’ve got enough snow up there, we’re okay,” said Quintana, pointing toward 14,049-foot Culebra Peak and its canyons — the watershed’s hallmark.

But for the better part of two decades, there hasn’t been enough.

A megadrought in this elevated desert more than 8,000 feet above sea level has lasted two decades, curtailing use and prompting adaptation plans for individual acequia farmers and ranchers. Depending on a great number of factors—including nature itself—each landowner must determine how to create and sustain their livelihood in a time of water scarcity.

“As a farmer, you’ve got to know, 'Okay, which piece of land will give you more of a product than the other?'” Quintana said. “So you irrigate that, concentrate your water on that.”

2021 was another year lean on snow. For Quintana’s fields, and the endless surrounding desert chamiso beyond them, supplemental rains made all the difference.

“This summer, oh man, we had all kinds of rain, which was beautiful,” said Quintana. “We needed it.”

Quintana and his family run cattle and farm an area in the lowlands of Viejo San Acacio west of San Luis. Just down the road is the oldest standing church in the state.

His grandchildren are fifth generation on this land. Quintana himself grew up irrigating these fields via the flood method with tarps and siphons off the acequia system. It’s more or less the same way it’s done today. Damming an acequia with a tarp creates a stoppage of water, and long, metal siphon tubes are placed into the resulting flow until filled. They’re maneuvered—Quintana demonstrates with a practiced toss—to run water out into the fields.

The morning of Thursday, October 21, we’re out on the rounds, traversing one of the long plots of land known as varas to pick up siphon tubes and tarps left over from the last irrigation.

170-plus years ago, the vara system provided each settler equitable access to crop land and the acequia waters running through. Water used to irrigate often eventually returns to recharge the stream system, and even tail waters are utilized. The goal, said Quintana, “is to give everybody a chance at water.”

These hand- and machine-dug acequias that deliver melted snow to fields are the oldest acknowledged water systems in the state. Dating back to 1852, the oldest ditches predate Colorado's statehood by 24 years. The system has been used ever since.

The gravity-fed network originates from seven major snow collection points high in the Sangre de Cristos into natural streams that interlace for miles, serving 300 properties, including many small and mid-sized farms and ranches.

Today, elected mayordomos of each acequia—around 73 of them—work with a local water commissioner within the Division of Water Resources to coordinate use of their acequia water. The mayordomo is often backed by a Comisión who handles maintenance and dues. As a state employee, the water commissioner follows a water administration list put forward by the state.

Quintana was water commissioner for the acequia system for 26 years. His firsthand knowledge was critical in this role.

Growing up, his parents ran a self-sufficient operation, largely of necessity. An established alternative economy of barter and trade among the greater San Luis Valley and northern New Mexico filled in the blanks. His family traded chicken eggs to a local store in exchange for flour, sugar, and coffee.

They had no refrigeration — “the garage was our refrigeration,” said Quintana. "That was roughing it at the time. Now, we’ve got it made. But that's the way we grew up.”

It’s not unusual for an elder member of the community to say they or their family had no concept of the Great Depression having taken place while it was happening.

100 years ago, the area was largely fueled by an economy of sheep and vegetables, with the backbone of self-sufficiency. Almost every area village — El Rito, Los Fuertes, San Pablo, Chama, San Pedro, San Luis, Viejo San Acacio, and San Acacio – had its own operative church and/or community center. Some had Moradas, meeting places of the confraternal religious order Los Hermanos Penitentes, a custom brought from Spain.

Today, the sole operating Morada in Colorado stands in San Francisco (also called El Rito or La Valley), the southeastern most village of the watershed.

At around 4,000 residents, Costilla County’s population is about half what it was at its height in the 1940s when Quintana was born. Each village was once populated enough to have its own school. The towns, some with boundaries indistinguishable to the untrained eye, played each other in basketball. Growing up, Quintana walked or hitchhiked the four miles into San Luis to see movies.

Quintana remembers K-12 consolidation to San Luis. Rivaling teams suddenly found themselves in classrooms together and on the same side of the court.

“It was tough, for a while,” he said. “It was really hard.”

These villages maintain their own style, bond, and folklore. And their own recipes: a local resident shared recently that she’s accustomed to the 20-minute round-trip to get the tortillas her husband prefers from a neighboring village (they’re fluffier).

Today, in Quintana’s fields, there is a leftover bovine feast after cutting, raking, and baling. Soon, the herd will be let loose to clean off and trample down what remains.

“We're going to bring all the cows over here,” Quintana says, gesturing to a long swath. Lines of trees bursting with fluorescent yellow and orange leaves give away the location of the acequias.

“Next week, I think,” he muses. “Before the snow flies.”

Traditionally, “After the first frost, when the snow is coming, that meant that it was time to go in and rastrojiar the garden and the fields, and harvest whatever was left,” the late scholar, poet, and lifelong acequia user Juan Estevan Arellano said in an interview at his kitchen table in Embudo, New Mexico, in 2009. “After that, you would turn the livestock loose to eat the stubble. That’s rastrojo.”

The resulting Spanish dialect borne of Southern Colorado’s history is still spoken. A unique mix of Spanish, Arabic, Nahuatl, and dialects within, Arellano explained, is composed—like DNA, like the acequia system—of these lineages of ancestors.

A loss of language occurred following forced cultural assimilation in class systems and schools where, post-Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, children were not allowed to speak Spanish, he said.

“It’s now we have forgotten mostly everything,” Arellano told me over a decade ago.

Arellano, whose own ancestry in New Mexico can be traced back to 1725, spent his life researching and writing to capture and preserve the history of land grants and local acequia agriculture. His books include translation of a 16th century text on Spanish crop practices. He discovered that it is the nuance within terminology that has evaporated along with the language.

“Most of the environmental language we have is embedded, so when you translate it into English, you lose a lot,” Arellano said. “A lot of the words come from Nahuatl or Arab, and though they may not be the true word of that language, the root is still there. It is not the same when translated into English.”

Losing nuance within culture, whatever the means, is a worry often expressed by the area's residents. Threats on water, land and heritage are sometimes tangible, sometimes looming.

Along with strained resources come difficult choices, and those who have taken on this lifestyle do not have days off.

“You have to be a little crazy to do this,” Quintana says blithely and with the grin of a ranking member. He pulls the umpteenth siphon from the ground and scrapes it lengthways into the bed of his truck.

“If you don't have it in here,” he says, tapping his chest over his heart, “don't even try it.”

Kate Perdoni is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.

This report, the first in a three-part series within the Río Culebra Watershed, was conducted through a fellowship with the Gates Family Foundation, Rose Foundation, and Rocky Mountain PBS. Read parts two and three.