‘Everything was a thrill’: 50 years later, Rick Steves reflects on his favorite trip to Europe

DENVER — When Rick Steves returns to the U.S. from a trip overseas, he has a 24-hour window in which he is still able to interpret his notes. After that, his hand-written reminders and observations scrawled on the pages of his black Moleskin turn to indecipherable scribbles. So instead of catching up on movies (or, heaven forbid, sleep) during a recent 12-hour flight from Istanbul back home to Seattle, Steves used the time to type out his notes for what will become the ninth edition of his guidebook to Turkey’s largest city.

This method, shambolic though it may seem, is a winning one for Steves, whose best-selling guidebooks and beloved public television program have made him one of the foremost experts on European travel. He has been a fixture on public television since the early 1990s which has made Steves, as Sam Anderson put it in The New York Times Magazine, “one of the legendary PBS superdorks — right there in the pantheon with Mr. Rogers, Bob Ross and Big Bird.”

This year marked 50 years since Steves went to Europe for the first time sans parents. Before graduating high school, he took out an ad in his school paper in search of a travel partner. The ad promised the chance to "feel the fjords and caress the castles." Steves’ friend, Gene Openshaw, accepted the offer.

With their hulking backpacks they named Bert and Ernie (maybe Steves had a hunch about a future in public television), Steves and Openshaw purchased a 10-week Eurail pass and budgeted $3/day for their “Europe Through The Gutter” trip that took them through the Alps, Scandinavia, the Iberian Peninsula, the Soviet Bloc and more.

Openshaw, left, and Steves, right, pose for a photo before their trip.

Fifty years later, that trip with Openshaw — who has co-authored many of Steves’ guidebooks — remains the venerable travel writer’s favorite European adventure. Rocky Mountain PBS caught up with Steves over Zoom, who joined from his home in Washington state following a trip to Poland and Turkey. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Rocky Mountain PBS: Let's go back to the beginning. You’ve said that the 1973 trip remains your favorite European trip that you've taken. What do you remember most about that first trip?

Rick Steves: The fear and thrill of being over there with no safety net that you've had from parents all your life. Nobody knew where we were. I was just with my best buddy. If we screwed up, it was our own fault. We had to sort of learn on the fly. Back then, there wasn't a lot of good information. There was a big language barrier. Communication was expensive and we were poor. It was a struggle — just the economic struggle of it sort of carbonated the whole experience. Every few days we'd put our money on the bed and count it up and divide it by how many days we had left and see how we were doing.

But it was really a $3 a day trip. And we were just like street urchins. Once you get older and risk-averse and wealthier, you can't have that experience again. And it was just great.

Everything was new, obviously. Everything was a thrill — just going into a market, sleeping on a train, having a vodka with a Russian. This kind of stuff was just wild.

But I think back now and I just think how politically naive I was. I didn't even understand where I was. “Is this Palestinian or Israeli?” I didn't know. I just was meeting all sorts of interesting people and so, you know, you get more mature in your travels. But the fun of traveling back then was really great. And, you know, I've sort of kept that backpacker edge in my travels to this day, which I really value.

RMPBS: You mentioned political naiveté. When do you feel like you kind of overcame that?

RS: I remember I was in Iran, in Tehran, and I saw poor people camped out — really poor people camped out — leaning up against a big shiny bank building. I remember that was a moment and I just thought, “Wow, there's so much money here, and that person's got none of it.” I remember in Morocco going south of the Atlas Mountains to a village where I had more money in my pocket than everybody in that village combined. But the irony was, I was afraid to eat the food and I was afraid to drink the water because I'd get sick on it.

So I had all the money, but I couldn't eat the food and the liquid that they were enjoying. And I remember I bought a Fanta. It was hot because there was no refrigeration. It was a hot bottle of Fanta. And I opened it and the glass broke off — not the bottle cap — but the glass broke off.

And I had to decide. I was really thirsty. I couldn't drink the water or I'd get diarrhea. I looked at that broken bottle top with all that Fanta in there, and I had to decide: am I going to drink that at the risk of drinking glass, or am I going to go thirsty? And I was so poor and out of my element and I ended up clenching my teeth and drinking it. And the kids around me were so poor that there were flies caked on their faces, and their eyes didn't even flinch.

You know, it was that total immersion thing. And I remember having a piece of bread and balancing it on the bottle cap of my Fanta so that it didn't touch the table. I mean, it was that kind of scary travel! Beds were big yellow sponges. That was the mattress and they were [shaped] like the hull of a boat. And my friend and I, we would fall together in the middle of a hot, sweaty night and just sleep in this room with literally a dirt floor that was, you know, it sounds horrible today, but, man, that was good travel.

RMPBS: Would you recommend that kind of travel to people?

RS: Well for a while, I actually inflicted it on people. People would take my first tours and I would put them in bad hotels just so they would experience a bad night’s accommodations so that they'd be more thankful for what they had when they got home. I really had this agenda to let Americans know, “Hey, we don't have anything to complain about.”

And it was a stupid kind of tour-guiding. But the sentiment was good, for us to get out of our comfort zone so we could appreciate what we have and be more thankful and also recognize there's a lot of suffering and a lot of need outside of our comfort area. Now, I’ve graduated to do the same kind of mission as far as experiential travel and exposing people and having people think about what they're experiencing without making them go into a dangerous, horrible rat house for a hotel. So we always have a refuge.

But back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, my mission was to expose Americans to reality. And to this day, I employ 100 people and we take 30,000 people on our tours every year. We have 1,200 tours this year. And our guidebooks — we've got more than 50 guidebooks that are the bestselling guidebooks in every destination they cover — and our mission remains [the same]. We like to joke that our mission is to inspire Americans to venture beyond Orlando. You know, Orlando is fine. Go there three or four times. But, you know, someday you could actually branch out and go to Portugal. You'll probably spend less and enjoy it more.

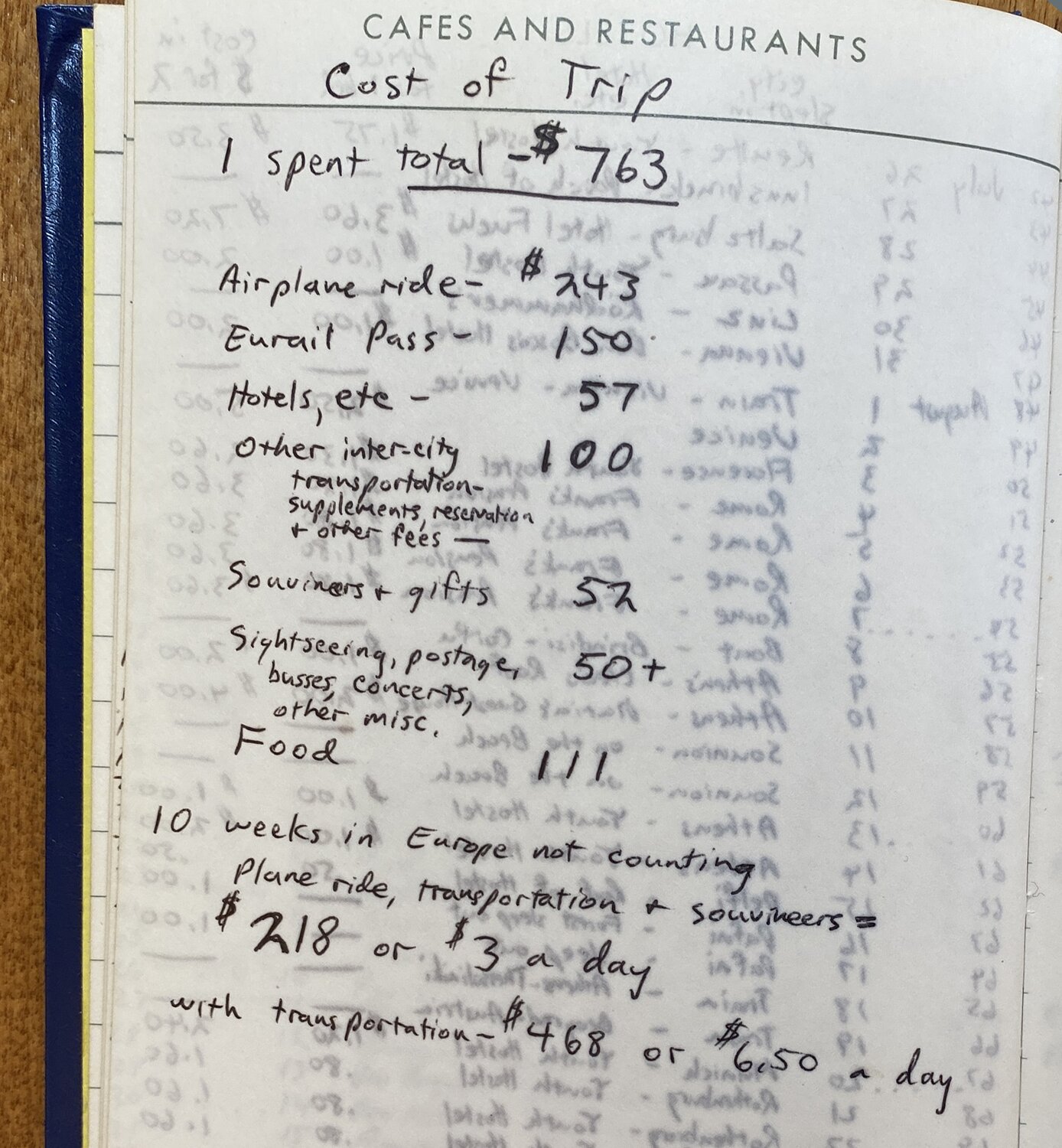

Rick Steves tallied the cost of his 1973 trip to Europe in a notebook.

RMPBS: You've talked a lot about second cities and the benefit of going to those as opposed to places like Paris or Barcelona. What are some second cities that you've been to recently that have surprised you in good ways?

RS: Well, Porto. I mean, they're kind of obvious. It's like Seattle and Tacoma — everybody goes to Seattle. What about Tacoma? Everybody goes to Paris. It's a great city, but what about Lyon? Everybody goes to Edinburgh. Great city, but what about Glasgow? They say a funeral in Glasgow is more fun than a wedding in Edinburgh.

These are the obvious examples. And they ring true to me right now. It's just that crowds are a bigger issue than ever before. The big issues now are crowds and weather. And people rely too much on their apps and there's too much screen time and all this Instagram crowdsourcing.

So what we have to realize is that a smart traveler takes seriously the problem of crowds. Crowds are worse now because everybody's going to the same places because we have this Instagram mentality where we all want to do the same thing and show it off on our social media site. So, respect for the crowd problems. What comes with crowd problems is a need to book things in advance.

That's a different thing now from before. I never would have booked anything in advance in the old days. Now, if you don't book in advance for a lot of great sites, you're not going to get anywhere. You're not going to get in the door.

I used to pride myself in total footloose and fancy-free travel. I didn't have any reservations for hotels or anything. Now, I still have the same free spirit, but I would be ill advised not to have things nailed down in advance. So that's important.

RMPBS: What are some other things that have changed since you began your travels?

RS: The weather's a big deal. You just have to take serious climate change. It's screwing people up. This summer I've done a lot of traveling and I've been in Morocco, I've been in Spain, I've been in Portugal. But I was there in April, and it was really good. I've been to Scandinavia and I've been in Iceland and Poland, and I was there in the dead of summer and it was really good. And I've been in Istanbul — I was just there last week, you know, late September — and it was really good.

Meanwhile, other people's trips were just drenched in sweat and boiling because they thought they could skate through and miss a heat wave. These heat waves are brutal in Europe. So we’ve got to take weather as a concern.

[Related: U.S., European heat waves 'virtually impossible' without climate change, study finds]

Of course, travel is a contributor to climate change. I believe we need to mitigate the carbon we create in a creative way, in an honest way. I spend $1,000,000 a year in my company mitigating the carbon produced by people flying to Europe for our tours. We give it to 10 or so different organizations that fight climate change through on-the-ground work in the developing world and government advocacy in the U.S. And we honestly mitigate — we create bad, but we create good and it zeros out. It’s not heroic. It's just baseline ethical. But we also have to have a stewardship obligation — if we're going to spend the carbon and the time and the money to travel — to do it in a way that is transformational so that we come home and become better world citizens. That to me is a beautiful thing.

And I don't want to be flight-shamed out of my travels because if nobody travels, this world is going to be a more dangerous place. But if we do travel, we should travel in a way that makes the world a better place. And that's not going to some elite golf course in the middle of a desert and flaunting your wealth. That's getting out there and getting to know people and realizing [Americans] are not the norm and there's a lot of things we can learn from and make the world a better place.

Rick Steves poses for a photo the day after his high school graduation in 1973. (Photo: Rick Steves' Europe)

RMPBS: How has social media changed international travel?

RS: I mentioned this thing about crowdsourced information. That's a new plague. When I started traveling, there was not enough information. People needed my books. Now there's too much information, and what I do is curate information as much as produce it.

There's too many superlatives, there's too many first-timers that are writing things up like they're experts and there's too many people that just follow them like they're experts. It's the whole TripAdvisor thing. People are doing wacky things because it's number one on TripAdvisor. “Everybody else is doing it. It must be right, so I'm going to do it.” And if you know how to travel, you look at that and you kind of laugh. You kind of just think those sorry souls, you know, they just don't have good information. That's going to be the challenge for our whole society going forward with AI and everything with crowdsourced information: what is the information that you're taking in?

There's a challenge for people to be in the moment. When we were filming in Venice, it was hard to find anybody on a gondola being romantic. They were ignoring their partners and taking pictures. So that's a sad thing.

RMPBS: Has the perception of international travel changed since you started doing this professionally?

RS: Fifty years ago, people said “bon voyage.” Now they say, “have a safe trip.” It's a pretty fundamental difference. It really speaks volumes. Now, people say “Are you sure you want to go over there? It's dangerous.” That's been parallel with the evolution of our news media from Walter Cronkite to sensational political agenda news. Because if it bleeds, it leads. You know, if you want to make money, you’ve got to have clickbait. You’ve got to have more people watching. And if you don't have a very sophisticated viewing audience, everybody becomes afraid because everything's amped up.

When you travel, you realize it's not that big of a deal. Every time I do an event, people ask me these questions and I just kind of go, “Really? You're worried about that?” Go there and see. Russia is not in Poland! It's safe to go to Poland. You know, a train just crashed in the Alps. That doesn't mean you can't go to the Alps. Somebody was just shot at a mall. It doesn't mean you can't go to malls. It's a big world. There's 20 million people in Istanbul. There could be a bomb every day and it would still be a safe place to go. So for me, the irony is the less we travel, the more we should be afraid.

And if we're really afraid, we need to get out there and get to know our neighbors. That is critical. I was just in Oslo and there's a bench in Oslo in front of the Nobel Peace Center there. The bench is shaped like a big semicircle. Two people cannot sit on that bench without coming together. And then there's a Nelson Mandela quote in front of the bench that says, “The best weapon is to talk to each other.” And the whole idea is we got to talk to each other when we travel, to talk to each other. If we're afraid, we build walls. If we're smart, if we care about stability, if we care about our children's reality, if we care about peace, we need to build bridges.

So I'm more enthusiastic than ever about my work as a travel teacher. And just from a practical point of view, it's better now than ever. So it's a great time to be traveling and it's an important time to be traveling.

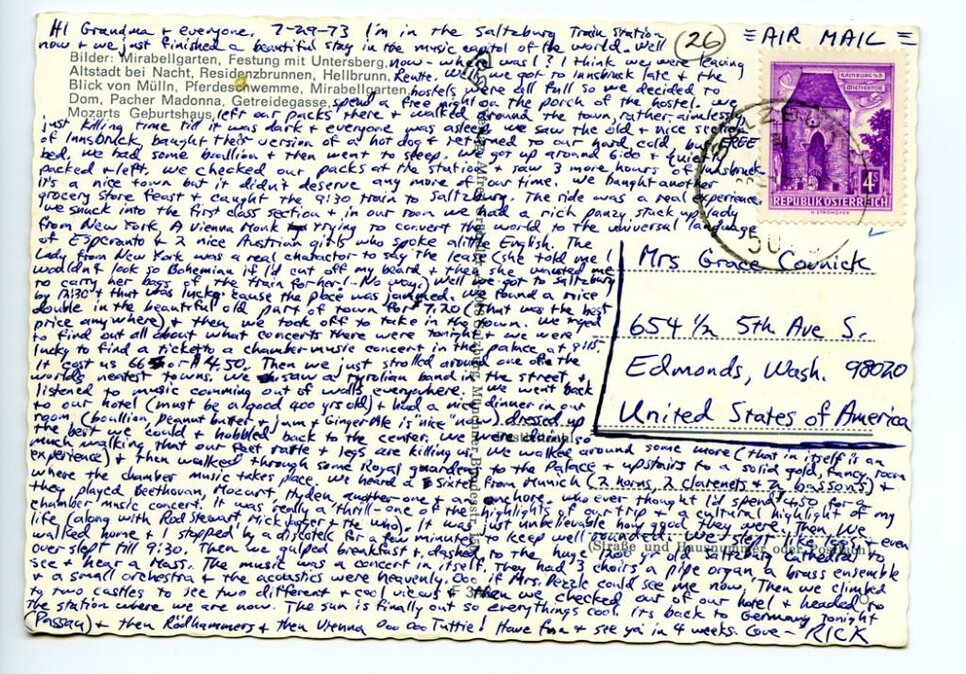

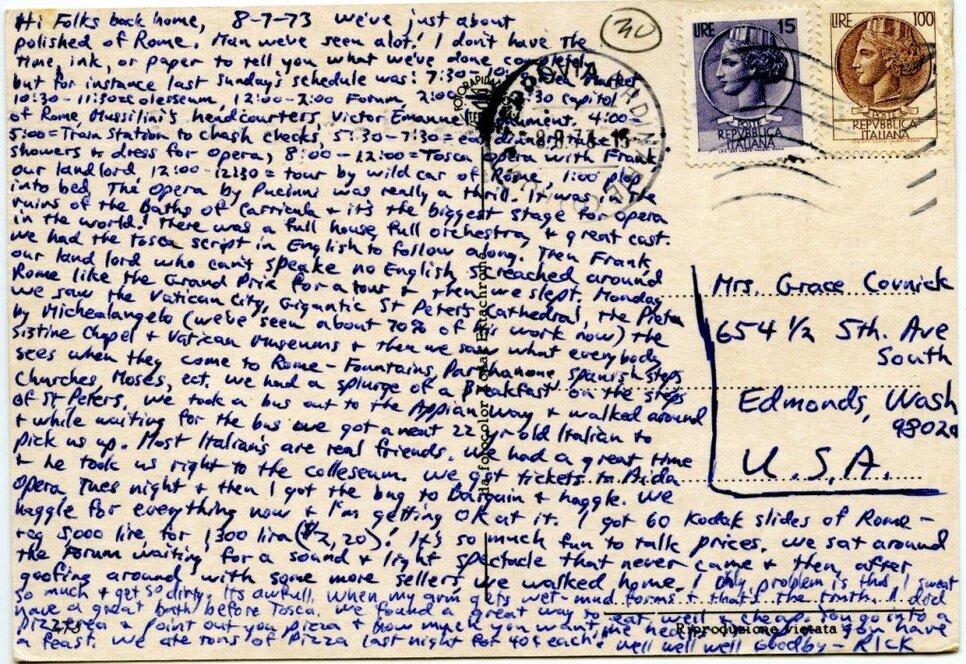

Steves sent postcards back home to Washington during his 1973 trip to Europe. Above, you can read postcards sent from Salzburg, Austria (left) and Rome (right).

RMPBS: Do you think that practicality — the lack of language barriers, the ease of currency exchange — has taken anything away from the travel experience?

RS: Yeah, it's taken away the adventure. You know, I travel risk free. I can accomplish a lot more. I've got it lined up and the ducks are all in a row. I set off on a six-week trip and I know what I'm going to do every morning and every afternoon. I've got guides lined up. I've got my admissions figured out. That's good. But it also takes away some of the serendipity.

So I think it's more important than ever when serendipity knocks to say, “Yes.” If you have an opportunity, grab it. If it's a mistake, that's okay. But it's probably going to spice up your trip. We can get it too locked down. Some things are just bad for my soul.Sometimes when I'm doing my work with my TV crew, the local tourist board will put us up in a fancy hotel. I don't enjoy it. You know, probably one of the most expensive hotels in the city, but it just builds a wall between me and what I traveled so far to see. I'd rather be close to the ground. I'd rather be able to make mistakes and rather have to figure out how to use the transit, you know?

RMPBS: You keep the first-time travelers in mind when creating your guidebooks and your television program. How do you kind of tap into that perspective as someone who has half a century's worth of European travel under your belt?

RS: That's a forte of mine, I got to say, because I am tuned into how overwhelming it must be to be a first-timer here that doesn't speak the language. And I'm working on this [Steves holds up a draft of an Istanbul travel guide] and I know how overwhelming that city is. And I'm just so excited about this new map I'm making, which is a very easy, schematic map of the public transit. But I also know that people can't say a single word of these places. Nobody knows these words, even if they had all the words there with pronunciations. People can't remember those words. It's got to be done in a way that an American traveler or non-Turkish traveler can get the brain around.

So I stand on a square and even though I used to know it really well, I forget over the years. So I enjoy being befuddled and I just love that. So embrace the joy of being confused and overwhelmed when I'm in a new city because a day later I feel very comfortable at it.

Kyle Cooke is the digital media manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at kylecooke@rmpbs.org.