One year later, Ladyfingers Letterpress reflects on COVID-19 impacts

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — March 12, 2021. A morning like many others.

Bijou Street’s small business row begins to populate. Sidewalk sandwich signs appear, advertising store wares, online shopping, and COVID-19 mask requirements. Across the street, Acacia Park slowly comes to life with dog walkers and city dwellers on their morning coffee strolls.

Inside a brightly decorated storefront showcasing a cornucopia of children’s books, games, and crafts stands an ever-vibrant array of local goods. The computer behind the sales desk of Ladyfingers Letterpress dings repeatedly, each sound representing another online order. The phone rings with requests, and an SUV glides into the parking space reserved for curbside pickups.

Online alternatives, increased phone communication, and sidewalk exchanges have all become mainstays of the past year as this family owned and operated small business navigates the continually choppy waters of a pandemic.

This particular date brings with it a somber notation: March 12 marks the one-year anniversary since Ladyfingers officially closed its doors to business as usual.

The downtown storefront opened in June of 2016. Home to many creative enterprises in Colorado Springs, Ladyfingers soon became a go-to for inventive, one-of-a-kind gifts, small-scale art exhibitions, in-store demonstrations and classes — and a continued haven and respite for underrepresented voices.

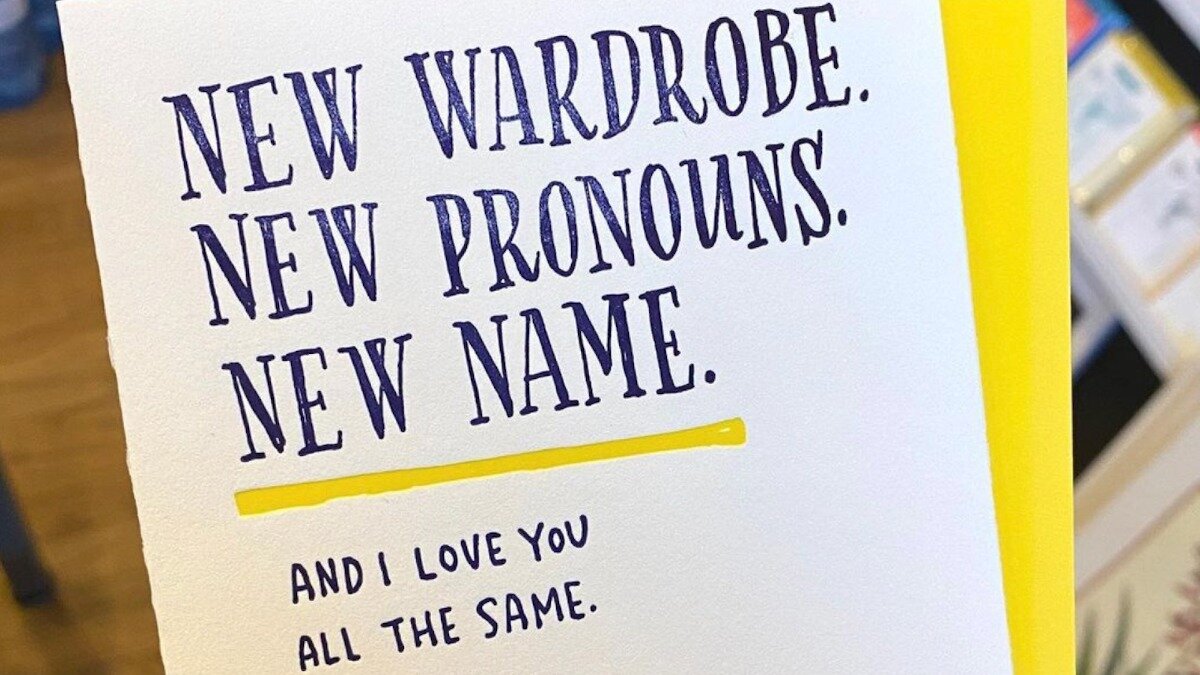

“We especially focus on highlighting the work of marginalized folks, and really providing a place where people can see themselves reflected in what we’re providing,” Calderini explained.

“For us, inclusion is about not only feeling safe, but feeling seen, held up, respected, and celebrated. And we hope to attempt to provide that in some capacity for our own community — because it certainly is something we all can do better with.”

“We make cards and products that we believe in,” Calderini continued. “When we start the process of designing a card, often times we’re looking to fill a gap in the marketplace. For example, right now we’re working on a series of cards for celebrating parents. And those parents may not identify as a ‘mother’ or ‘father,’ and may not celebrate Mother’s Day or Father’s Day. How do we help recognize non-binary or trans parents? And how do we help their families celebrate them? We’re working with each other and our community to write these cards, to design them, and letter them by hand. Then we make the plates in-house, and the printing happens right here, on these presses from 1942.”

Ladyfingers sells their line of stationary and greeting cards to stores all over the country — and the world. Some 800 stories stock their goods, according to Calderini.

In the last year, Calderini said, those 800 retailers — most of them independent, family-owned boutiques similar to Ladyfingers — were also struggling. Stores closed, some for good. For the most part, large-scale orders stopped rolling in.

Ladyfingers responded by shifting focus to their online store. They continued to provide customers with personal recommendations, email exchanges, and lively Instagram discourse. Calderini said she is grateful to utilize technology to develop an even closer relationship with customers near and far.

“I respect and understand that not every business has the privilege to make these choices and changes,” Calderini said. “For us, though, we feel like this is what we’ve been called to do in order to take care of each other and our community.”

In turn, Calderini said, “the community has just completely embraced us and helped us get through.”

Now, one year later, Calderini said they are finally seeing a glimmer of hope in rebuilding an in-person market.

“We have been very lucky to receive some orders in the last couple of months from shops who also are feeling like they’re on the edge of being able to open safely again,” Calderini said. “And we’re seeing that these stores really want to focus their attention on supporting small businesses that they want to see continue into the future — like us.”

Before they were ironing out every small business owner’s journey of “a new normal,” Calderini and Torsone had a robust national roster supplying not only to retail stores, but also to wholesale distributors.

Pre-pandemic, “we also sold to a handful of larger corporations,” Calderini said.

One of these was Paper Source, a chain of over 150 paper and stationary gift stores across the country. “We have been selling to them for years, and had a great relationship,” Calderini explained.

Like many stores, Paper Source was not immune to the hardship brought on by the pandemic; the biggest challenges included maintaining commercial leases and keeping employees safe.

The result was a massive drop off in Ladyfingers’ wholesale business, Calderini said. “It was kind of like crickets for the greater part of the year.”

Then, another glimmer of hope. “We received a flurry of orders from Paper Source right at the end of 2020 to ship in January and February. And again, we thought, ‘Oh, this is really exciting and encouraging — they must be feeling hopeful, too!’” Calderini said.

Once again, the uncertainty of the pandemic proved that all is not as it appears.

“Unfortunately, Paper Source has declared bankruptcy,” Calderini said, her wavering voice revealing the complexity of the situation. “It’s unclear now if we will ever see payment for this large batch of rushed orders that was requested right at the end of the year.”

Though Paper Source stores across the nation are set to remain open as a new buyer is sought — except for the 11 locations that permanently closed due to the pandemic — what the bankruptcy means for artists who sell to the company remains to be seen.

For Ladyfingers, outstanding invoices from Paper Source total some $23,000.

Shaking her head, Calderini takes a deep breath.

“It feels like an absolutely appropriate and frustrating way to be heading into the one-year anniversary of when we closed our shop,” she said. “It just really has been a challenging year.”

Calderini is also thinking about the hundreds of other small family businesses impacted by the bankruptcy filing. “These are creatives, artists — folks who have fought so, so hard to endure as much as they can in the last year,” she said. “And then to have this happen, and from a large corporation, feels very frustrating. But it also feels somehow not at all surprising… which is part of, I guess, what fuels the frustration.”

Still, she said, their online business and client community rallied in support.

“It was incredible to see how quickly people were communicating about it,” Calderini said. “And that maybe felt like a bright spot of all the change that’s happened in the last year. These networks of support have grown amongst business owners and social media communities. Immediately, people said, ‘What do you need? How can we help?’ It is such such a gift that people just show up.”

Calderini said she and Torsone have redefined their notion of success.

“We knew that this year would be one of the hardest we’ve seen as a family, as a couple, and as business owners,” said Calderini. “Really for us, survival has been the key. I have no expectations except to try to live through the year and try to help other people do that in our community.”

Ladyfingers doubled down on its commitment to selling goods and products from other local makers, adding thousands of items to their online shop, which previously showcased only Ladyfingers creations.

“I would say we’re definitely a small business here at Ladyfingers,” Calderini said. “Our whole enterprise is run by myself, Arley, and our one full-time employee, who also happens to be a family member.”

This small but mighty team updated their entire sales system, reorganized inventory, brought hand-lettering classes online, and became “expert shippers,” Calderini said.

Although the lack of communication surrounding the abrupt bankruptcy filing from Paper Source added to the blow of the news, Calderini said it also inspired her to continue an honest, upfront demeanor with her own clientele.

“We don’t necessarily measure our success by sales,” she said. “We’re much more interested in connecting with people about where they are, and seeing them, and having them see us.”

In a series of live Instagram feeds, Calderini and Torsone explain changes in store policy, showcase inventory, and even share hard news for their business.

“The past year has definitely caused Arley and I to take the conversations that we typically would’ve had in our store with people, and to have them online,” Calderini said. “We’ve always been people who think that it’s important to really share with others. It felt like being honest and transparent in every way we could with people about what we are facing would also just acknowledge how hard it is for everyone else.”

As a result, they’ve felt massive support. “We’re extremely lucky to have a community of people here in our town, but also a community of people online from all over, who have been just ardent supporters,” Calderini said. “We have the absolute most incredible clients who have stuck in there with us this past year, in all the various forms that has looked like.”

It has also expanded the notion of what an “accessible” business can look like, she said. Some discoveries will remain staples of their business post-pandemic.

“Curbside pickup will be an option evermore for people,” Calderini said. “And when we reopen, we plan to have at least one day a week that is by appointment only for people, for any reason — there’s no need for them to even identify what it is.”

A big lesson of the past year, Calderini said, has been learning to ask the community for help.

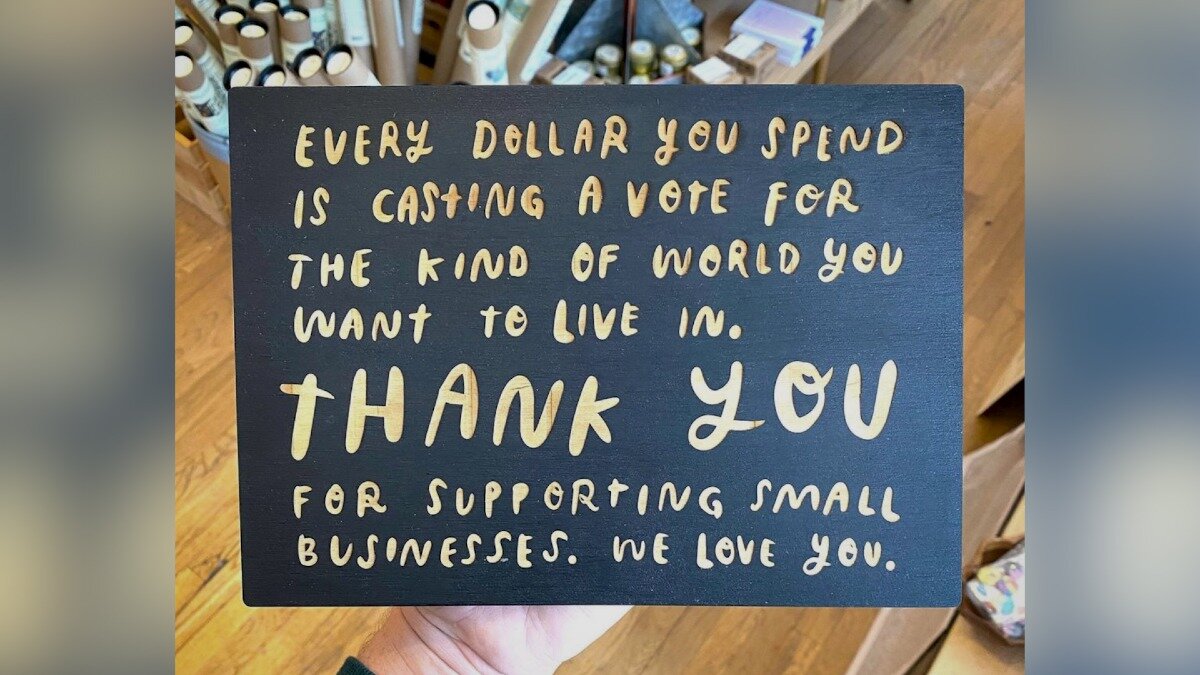

“It has been incredible,” she said. “All those things you hear about shopping local are true. If you shop in your own community, more of the money stays here and is reinvested into families and communities.”

With this community support, Calderini said, Ladyfingers Letterpress “can speak up about things that matter to us. And we can raise up the voices of other people in our community, too.”

“We've been closed to in-store shopping for the majority of the year,” said Co-owner and Printmaker Morgan Calderini. “We closed March 12, 2020, of our own accord and our own choice — even before the state mandate.”

Though taking risks is part of any small business owner’s day-to-day, for Calderini and her partner in life and business, Arley Torsone, rolling the dice does not apply when it comes to community health.

“We have been maybe more conservative about the risks we’re taking than a lot of other businesses,” Calderini said. "But it’s also the case that we felt like we could shift our business to online sales, and that it was possible for us to reduce exposure for the benefit of our whole community.”

Calderini and Torsone pivoted their store “to what almost feels like a fulfillment warehouse,” Calderini said. “We are shipping just so many boxes, and people are picking orders up on the curb.”

“It’s a huge shift in the kind of business that we had before,” she said.

And it hasn’t been easy.

“I really miss people,” Calderini said sadly. “There’s just no substitute for a hug.”

Ladyfingers Letterpress forged a name for itself by providing a tactile experience, doubling as an in-house print shop and studio. Putting their process on display — and the customer interaction that comes with that — has always been pivotal to the Ladyfingers experience, Calderini said.

“We like to share the environment of our studio with folks who are in the store,” she said. “I’m excited to be at a point in the future, hopefully soon, where we can have those interactions in the shop, and just connect in person again.”

Calderini and Torsone have been in business for a decade, first in Rhode Island, where they met, fell in love, and married. The fledgling Ladyfingers blossomed by offering custom, hand-drawn life announcements and invitations.

Calderini, who grew up in Colorado Springs, never anticipated returning. But then the summer of 2013 came, and with it, the raging Black Forest Fire, destroying her family’s home.

“It was not something we ever saw for ourselves, but we came back,” Calderini said. “We felt there was space for us in this town. We didn’t expect to stay. But now that we’re here, I can’t really imagine being anywhere else.”