Q&A: Nuclear Princeton short film examines the impacts of uranium mining on Navajo lands

Navajo Nation — In the wake of blockbuster hit “Oppenheimer,” a movie highlighting the scientific development of the nuclear bomb through the Manhattan Project, stories of the Indigenous lives impacted have remained untold.

During World War II and into the 1970s, the United States mined for uranium on Native American land. Indigenous people were employed in the mines without being warned of the health and environmental impacts, resulting in high rates of lung cancer and other ailments.

Nuclear Princeton, an undergraduate project at Princeton University, hopes to bring this reality to light, in part through a short animated film titled “Titration: Radioactive Waste, Princeton and the Navajo Nation. ”

Princeton University was integral to the Manhattan Project and other developments in nuclear science.

Nuclear Princeton unites undergraduates from the university in acknowledging this history, and using their platform to bring light to the impacts these scientific advancements had on Native lands and people.

“Titration: Radioactive Waste, Princeton and the Navajo Nation” was a collaboration between Nuclear Princeton and Twiddle Productions, a Hawaii-based multicultural multimedia studio specializing in animation, production and education.

The short film centers Princeton professor Nathan Furman, who was part of the Manhattan Project, expanding the context to educate viewers on the dark side of the work in which members of the Navajo Nation were hired to mine for uranium without being informed of the impacts it would have on their land and bodies.

It follows "ghost-like" animations through modern landscapes, telling the story of the uranium mines through the perspective of today's researchers, and the miners who were impacted.

Rocky Mountain PBS sat down with Twiddle Productions’ filmmaker Michael Q. Ceballos, Princeton professor and cofounder of Nuclear Princeton Ryo Morimoto, and the writer of the film, Princeton alum Thomas Dayzie to learn more about the meaning behind the film.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Rocky Mountain PBS: Thank you for being here! To get started, tell us how this film collaboration came to fruition.

Ryo Morimoto: We wanted to reach out to younger generations, especially people in the community. So how can we convey the complex ideas of the nuclear science and technology to them? That was one question.

Another question was, what we're doing is to basically revive the archives that does not really exist. So we're trying to tell the stories of the people who didn't have a voice. When there's no written materials, how [can we] ‘animate’ their stories?

That's when the idea of animation came.

Thomas Dayzie: We looked for animators who were either Indigenous themselves, or worked a lot in the Indigenous community and told Indigenous stories. And it turned out that Mike and Twiddle were the best fit and very, very happily so.

Michael Q. Ceballos: Once they contacted us, it was getting to know each other, learning about the project. We were speaking two different languages: me, in production, and them, with the extensive knowledge on Indigenous issues.

Then, working with Tommy, who had this incredible idea of bringing this all together, to get to the point where we can start designing characters and come up with a concept — linear, but ethereal in a way.

RMPBS: Stepping out of your professional roles for a moment, what are the personal ties or interests you had in this particular topic?

TD: I am Navajo myself, and a member of the Navajo Nation. A lot of the people in my grandfather's generation were directly impacted by uranium mining. Even to this day, uranium mines mark the landscape of the Navajo Nation.

My grandfather himself worked in a uranium [refinery] in the early 1960s. Thankfully, not for that long, because most of the people he worked with at the refinement mill ended up dying prematurely from different ailments.

It was a perfect way to bring together these two spaces — the Princeton academic environment, and the landscape of the Navajo Nation.

The people of the Navajo Nation were affected by the major leaps in science which were made in Princeton. And it was a way of recognizing the legacy - recognizing science as an activity which has real world effects. And to give a voice to those who are affected in a bad way.

It was really wonderful seeing the world that I had grown up in and that I had researched come to life in animation with Mike, who made sure that everything was correct. All of the details were authentic.

Navajo Nation, near Monument Valley.

Photo courtesy: Thomas Dayzie, Nuclear Princeton

RM: As a researcher, I studied the Fukushima nuclear accident. But personally, I’m somebody who is from Japan working at Princeton University.

Before coming to Princeton, I didn't think too much about Princeton's connection to the development of the bombs and other stuff.

But as I came to the university, I realized I'm working at the institution, which was one of the essential places where the development of the bomb happened.

I'm from not too far from Hiroshima. I've heard about the stories of the atomic bombing from my grandparents.

It was weird, because I'm benefiting from the prestige and resources of this university, which is made possible by its participation to this military project, which impacted the people in my country.

So I was that thinking, what are the things that I might be able to do?

Around this time they were filming Oppenheimer. That really led me to think, ‘I want to do something to stop the reproductions of that kind of story.’

To me, it's personal because of my Japanese heritage, my trajectory, my career at Princeton, and what it means for a Japanese individual to work at this institution.

MQC: I've always been interested in the cultural stories of Mexico, but have never acted upon it. But coming to Honolulu and seeing the talent that is here and the passion for Indigenous stories really started everything with the whole project.

RMPBS: Speaking of Oppenheimer, can you tell us how this piece differed from mainstream media, and what you did to fill those gaps?

RM: The honest answer is that none of us are specialists in the media field. So that ignorance was helpful, not to play into the particular sort of narrative arc that one might have to dramatize.

It is important to point to the detrimental environmental impacts from this scientific activity, but we are not here to engage in the ‘suffering pornography,’ so to speak.

Part of the issue is that this suffering narrative hasn't worked because that only gets sympathy for a short time. So we wanted to have something long lasting.

Nuclear science and technology still impact us today. So how can we include other voices into the conversation about something that matters to all of us?

I come from the background where I honestly believe that one of the things that we share collectively is the fall out from the nuclear bombings and the testings that happen. That each individual body carries that legacy.

The great thing about me partnering with Native students is that the many of them have this same belief that we're kin with others. So here we're playfully using this idea to think about how we can emphasize that kinship.

RMPBS: Touching a bit more on the intergenerational aspect, what are some impacts from the uranium mining that Navajo people are facing today?

TD: The biggest negative impact, of course, is the impact on human life.

There are a lot of people who have health defects specifically because of the mining and the damage to the environment. Mines led to a polluted environment in the Navajo Nation, which there wasn't education about at the time.

While mining was happening, the negative health effects were told to the ‘overseers’ of the miners, but not to the miners.

The process to get reparations for that is also complex. How do you prove that your sickness is due to the radiation?

It's hard to conceive of some way to right this wrong when it's people's lives that were affected.

Uranium mining has determined a lot of the landscape of the Navajo Nation in a way that even just cleaning it up will not change.

It's part of the history now.

RM: And then if the government decides to really make an effort to do the cleanup, who are the laborers who would attend to this stuff?

They are most likely local people who need a job. So there's a cycle happening.

Because of what's happening in terms of climate change, nuclear is still considered one of the most vital sources of energy.

The world is trying to basically triple the nuclear energy output, which means potentially reopening some of the uranium facilities, including the ones in the U.S. and and perhaps in the Navajo Nation.

This history may continue on. So I think we are at a very important moment right now.

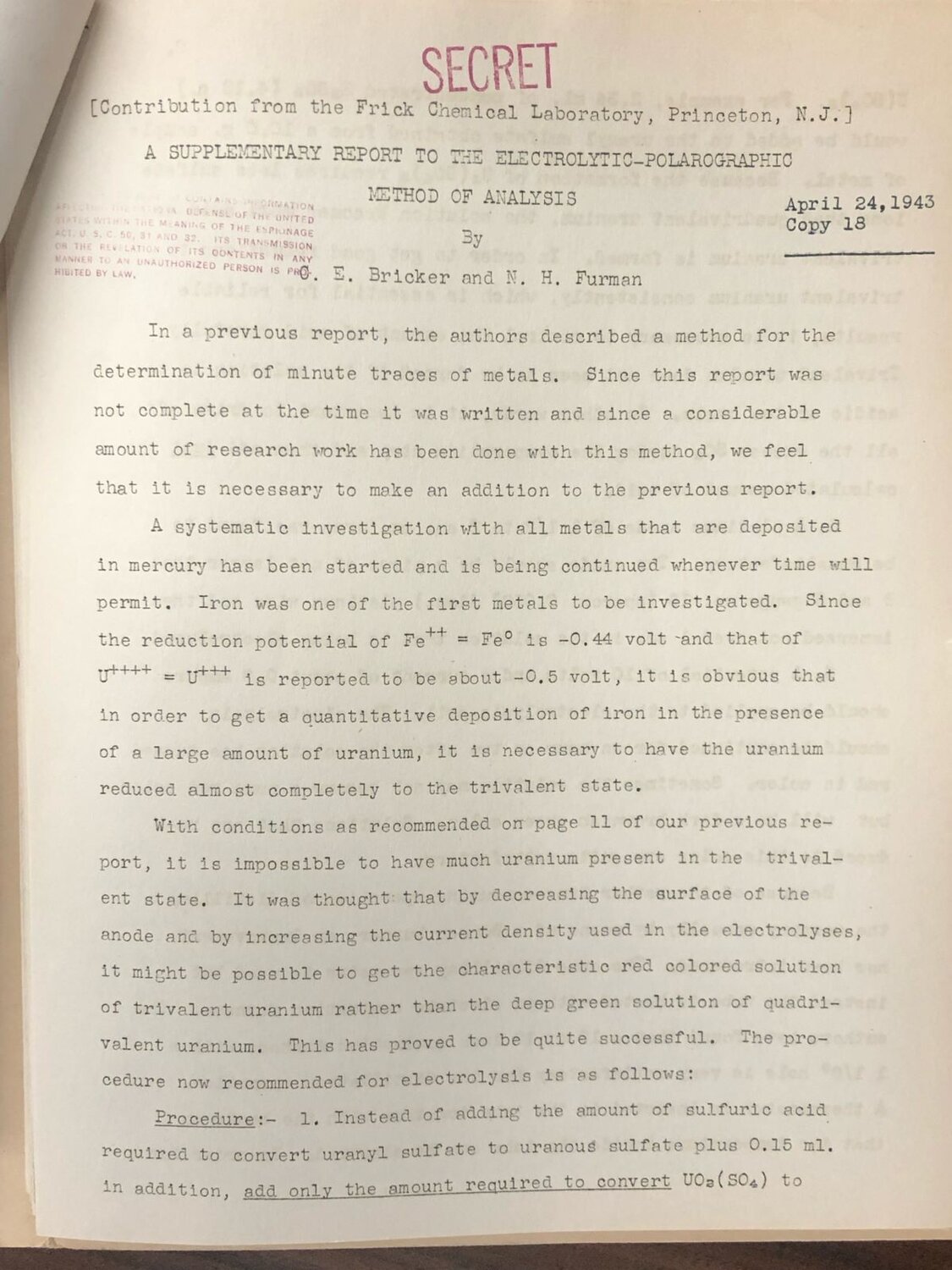

A 'top secret' Manhattan Project paper on Titrations, co-authored by Furman.

Photo courtesy: Nuclear Princeton

RMPBS: Tell me about any epiphanies you had during this process.

MQC: Well, for me it was the whole thing. I'm fortunate that with each project we do, there's there's new knowledge that I personally gain, whether it's about language loss or cultural loss and resurgence.

This one in particular was really all those. The thing that struck me the most were the statistics at the very end and how the traces of radiation is still found in babies.

I thought that was very powerful because it also lends itself to that message of knowing that this is still a real thing.

TD: I had been aware of this problem on the Navajo Nation, but it's not really talked about that much. I guess like even among my community, it's kind of hard to frame this problem because it seems so big, and makes you feel kind of hopeless.

I think it was really important for me to do this because it showed that there was a way to formulate people's voices and perspectives on this to be not be silent, to show people that this happened, how it happened, and how it is still happening.

RM: This was one of the first projects where all of us really participated. So through this, I really learned about each individual student.

I also learned about the power of nuclear banks in general because usually when we think about the nuclear materials in terms of the bombs and energy, the fundamental of its technology is to split something apart.

But through this process, we learned how nuclear things can also bring disparate entities together.

We were coming in from all sorts of different backgrounds, different nations, to come together to a message that is bigger than all of us.

Elle Naef is a multimedia producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. ellenaef@rmpbs.org.