Mother is ‘desperate’ to warn others about the harms of THC concentrates

HIGHLANDS RANCH, Colo. — Johnny Stack used to tell his parents the mob was after him and that they were in on it. His mother says he couldn’t really explain why.

“He just always had this sense of paranoia or that people were watching him or after him or that everybody knew who he was,” Laura Stack said of Johnny’s behavior before his death in November 2019. “It was a very strange pattern of thinking.”

Johnny fell from the top of the parking garage at RTD’s Lincoln Station in Lone Tree. His death was ruled a suicide and his behavior suggests he was experiencing a mental health crisis.

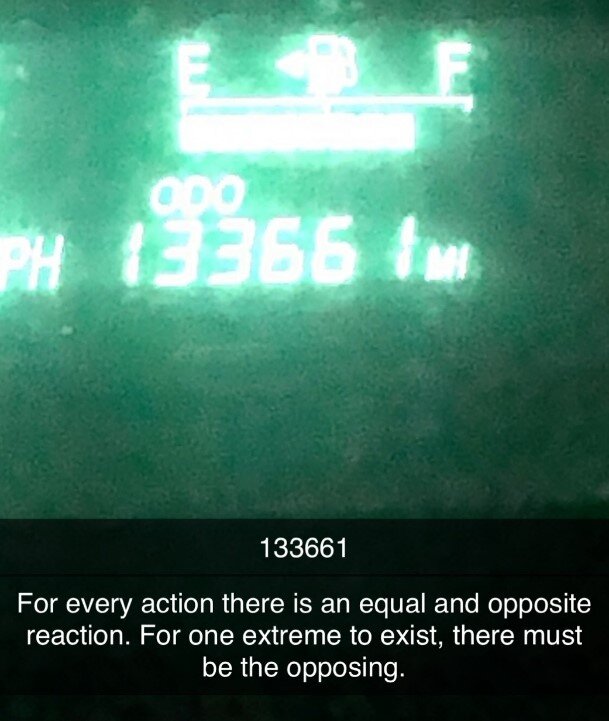

Five minutes before the fall he took a photo of his car odometer. It read 133661. He posted the photo on Snapchat with the message: “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. For one extreme to exist, there must be the opposing.”

“[Experts in psychosis] don’t think he probably actually thought he would die,” Laura said. “There was a video of him from the RTD station that the cameras took in the parking lot showing that he spread his wings as if he literally thought that he was going to fly right off the building. I don’t know if he intended to die. I’ll never know what was going through his mind. But I do know that if it hadn’t been for marijuana, he’d still be here today.”

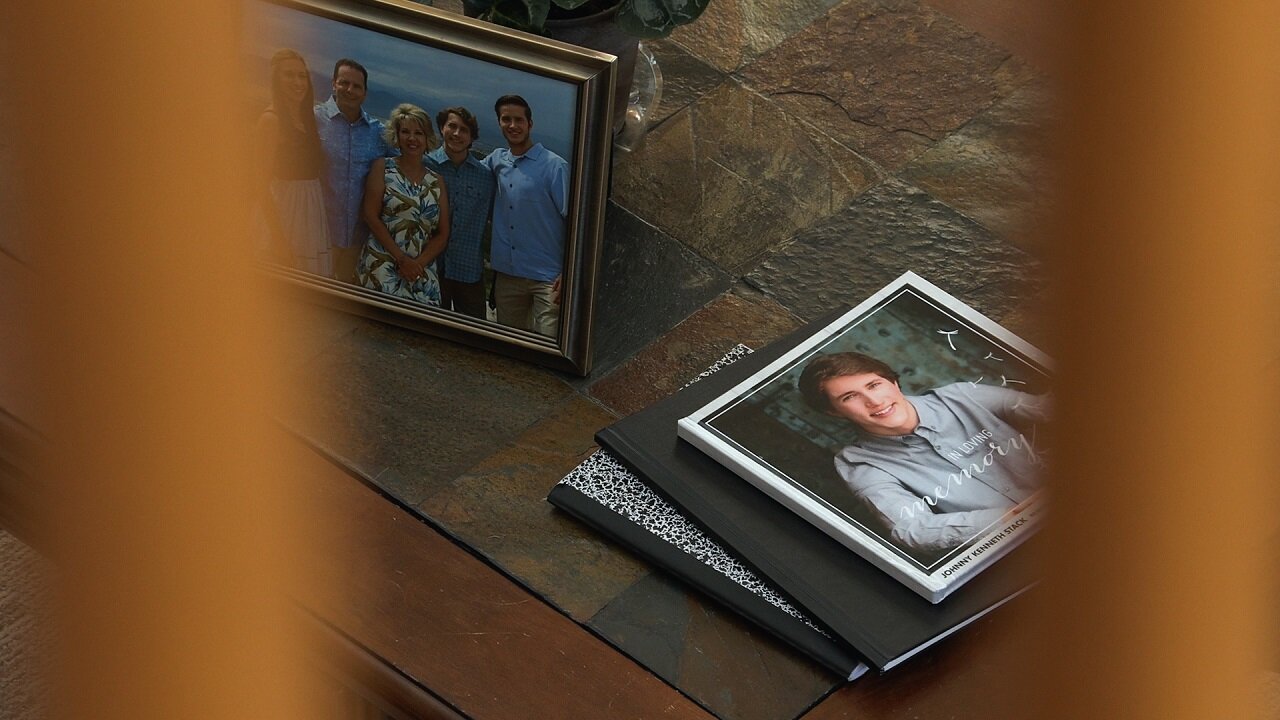

Johnny’s family scattered his ashes in Hawaii the February after his death on what would have been his 20th birthday. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, leaving the Stacks to mourn in isolation.

“And then I got really angry living here in Colorado and just the availability of this drug and these dabs, these concentrates, these vapes, these edibles. And these kids don’t have any idea how potent this stuff is and how it’s harming their brains,” Laura said. “And everyone wants them to believe it’s so natural and harmless. And it’s legal. It must be safe. Just all the false narratives that these kids buy into, that these adults are telling them and not protecting them.”

For the next six months, Laura wrote about Johnny. She produced 300 pages. “I wrote his life and death story in a way that I hoped other people would recognize their children and hopefully save them. Can’t save Johnny, but we can maybe keep it from happening to someone else,” she said. “So amazing how many people call me and they say, ‘I read your story and you can substitute my son with yours. And it’s the same story.’”

Johnny was 14 when he first tried marijuana at a party. It was 2014, the year Colorado became the first state in the nation to legalize recreational marijuana use for people 21 and older. Voters had passed Amendment 64 two years prior to full commercialization.

Johnny’s parents dismissed his first encounter with marijuana as a relatively harmless bump in the road. They admit they had no idea their son had begun a journey toward addiction. “I thought to myself, you know, it’s just weed, right? I used it. It didn’t hurt me. I had no idea how wrong I was,” Laura said. “It’s the dirty little secret of the marijuana industry that these high potency products can trigger psychosis in youth. There’s a campaign of confusion. They want to cast doubt on any study that comes out that hints that THC in the developing brain can actually cause mental illness and schizophrenia-like psychosis with delusional thinking.”

Johnny tried to stop using marijuana a couple of times. Laura says during those breaks he would recover. But he kept going back. He would eventually be diagnosed with THC abuse severe. “That was his diagnosis,” Laura said. “He had no other drugs in his system. It wasn’t laced with anything. This wasn’t the black market.”

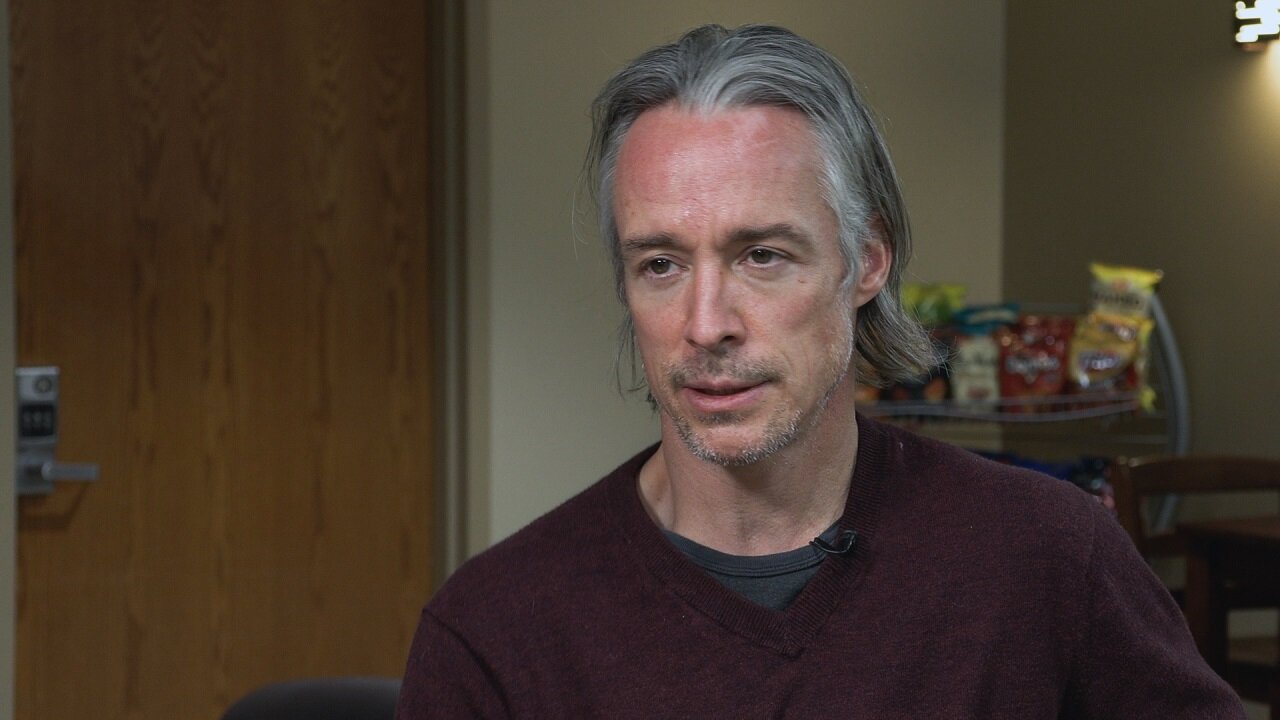

According to Dr. Chris Rogers, the Medical Director of Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health Services at the HealthOne Behavioral Health Campus in Aurora, suicide is the number one cause of death in Colorado for youth, ages ten through 19. And the number one substance found in their toxicology reports is THC, not alcohol.

“The data is very suggestive that your risk of having suicidal thoughts and potential suicide attempts also increases with the potency of cannabis,” Dr. Rogers said. “So, the younger you are and the higher the potency THC products you use seems to correlate to your risk for worsening depression and suicidality later in life. And then the higher the potency gets, it is fairly compelling that your risk of psychosis goes up somewhere between four- and six-fold with each use. The risk of addiction also seems to be correlated with that, such that we believe the data would suggest that one out of every 11 adults who try current cannabis products are destined to then become addicted. One out of every six adolescents … will go on to form a true cannabis use disorder or a cannabis addiction.”

Rogers works to increase awareness of how harmful today’s marijuana products can be, particularly for younger populations. And like Laura Stack, he combats misinformation from the cannabis industry and marijuana culture in general.

“A whole generation of Coloradans have been raised to think marijuana is medicine,” Rogers said. “And that’s one of the most alarming trends that we combat on a daily basis. I have kids as young as 12 years old who tell me they use high potency products such as wax, shatter, dabs, things that are basically rock marijuana. It’s THC distilled down into 80%-plus forms using butane and other harsh chemicals. And you use a glass pipe with a blowtorch similar to smoking crack cocaine or any rock product. And they use this nightly to help them fall asleep as if it were NyQuil and they don’t see any harm in it. The harm is evident since I’m obviously talking to them in an inpatient psychiatric unit.”

Both Dr. Rogers and Laura Stack point to how rapidly the marijuana industry has developed THC products that older Americans wouldn’t even recognize. And they say the potency of today’s best sellers are having devastating effects, especially in children.

“You can ingest marijuana any which way you think might be fun and we have no idea. This includes tinctures, edibles, vaporizers, suppositories, THC-infused tampons … there are no guardrails. If it’s got THC and you can make it, you can pretty much sell it in the state,” Rogers said. “These are products that kids describe much closer to like a heroin or methamphetamine addiction. They can’t stop thinking about using these products even though they know it’s ruining their lives. They can’t focus on their friendships, their relationships, their school. They also cannot stop using because it is that potent of an addiction.”

“[In 2012, Colorado] voters were thinking they were getting the Woodstock weed. That’s what they wanted. You know, they wanted this 10%, get a paper, put in some flower, roll a joint, pass it around and go to Denny’s, right? That’s what voters wanted. But what our kids got are these 90% shatters and oils and edibles,” Laura Stack said. “I don’t think that voters would vote the same way today if everybody actually understood what marijuana is.”

Rogers and Stack are also eager to highlight how easily children are getting and hiding their use of these products.

“Things like marijuana vaporizer devices … that look like an albuterol inhaler. So, I can look like I’m treating my asthma in the middle of class and I’m getting crazy high to the point that teachers talk about kids falling out of their desks,” Rogers said. “The market share of these high potency products has skyrocketed over the available time that we have data: 170% increase in market share between 2014 and 2016. The marijuana industry knows that if they can hook kids before their brains are fully developed, their chances of having a lifelong user are much greater. So, they’re exquisitely prone to becoming addicted.”

“These kids are fully aware of who the seniors are, who’s 18, who has their medical marijuana card and who’s selling,” Stack said. “It’s simple for kids here to get marijuana … it’s perfectly legal for an 18-year-old to go into a dispensary with a med card and buy marijuana and then sell it. So, we call this sometimes the gray market. It’s legal to purchase, illegal to sell it. But, people have the mistaken impression that these kids are getting it on the street or they’re getting it from the black market, or they’re paying somebody five bucks to go in and buy it for them. They don’t have to do that. They just get it from their classmates. They get it from their older brothers and sisters. Sadly, they get it from their parents.”

By 18, Johnny had obtained his own med card without his parents’ knowledge. After he died, the Stacks discovered pictures and videos on Johnny’s Snapchat account that suggest he was also selling marijuana products to younger children.

“He had no mental health, no physical health, no conditions that he should have been able to even get one,” Laura said. “We don’t even know who gave it to him because they protect the doctors… You can say, ‘oh, I have a migraine’ or ‘I have a backache,’ and you can get a medical marijuana card when you’re 18 and legally go into the dispensaries and buy this stuff that’s so toxic. And they don’t know because everyone wants them to be addicted in the marijuana industry because their primary consumer is that 18- to 24-year-old age group … it’s addiction for profit.”

Dr. Rogers admits parents are outmanned and outgunned by commercialized marijuana. “You’re fighting against … a multi-billion-dollar industry that is targeting your child, that is intentionally doing everything they can to change the narrative, to say this is safe, this is good, give it a shot. Let’s make it more enticing. Let’s make it more empowering, more euphoric,” Rogers said. “I think if you sit down with Laura Stack and try to say, ‘that’s a parenting problem,’ you’re either delusionally high or you just are a heartless human because these people love the hell out of their kids. They do everything they can for them, and they’re still losing kids by the hundreds to these addictive properties.”

In May of 2020, Laura founded Johnny’s Ambassadors. The nonprofit educates parents, teens and communities about the dangers of today’s high THC products, particularly on adolescent brain development, mental illness and suicide. She travels across the country with her husband John, who says he mourned Johnny’s death differently.

“I am proud that [Laura has] channeled her abilities into this direction,” John Stack said. “It took me a year at least to even be able to have this discussion.”

John and Laura Stack still marvel at how much marijuana changed their son. Before, he was busy with school and sports. He ran cross-country and track, played soccer and was a brown-green belt in karate. He had a 4.0 GPA until his very last semester of high school and scored a perfect 800 in math on his SAT, graduating with a scholarship to Colorado State University. He played the piano and guitar, participated in service projects and had a heart for the homeless.

[Related: Johnny Stack tribute video]

John remembers the strained relationship he had with Johnny before his death. He chalked it up to typical teenage behavior. “I always thought that we had time,” John Stack said. “I always thought that, you know, someday we would laugh about some of the things that happened when he was a teenager. And I never got that chance.”

Jeremy Moore is a senior multimedia journalist with Rocky Mountain PBS. You can email him at jeremymoore@rmpbs.org.