Headless in Fruita

FRUITA, Colo. — The streets of Fruita in June looked like any other small town in the middle of a festival: Pop-up tents with t-shirts and trinkets, local food and blaring music. But at this particular festival, which started in 1999, there was a mascot walking around. It was a chicken with orange legs and feet, a white body and wings and ... no head.

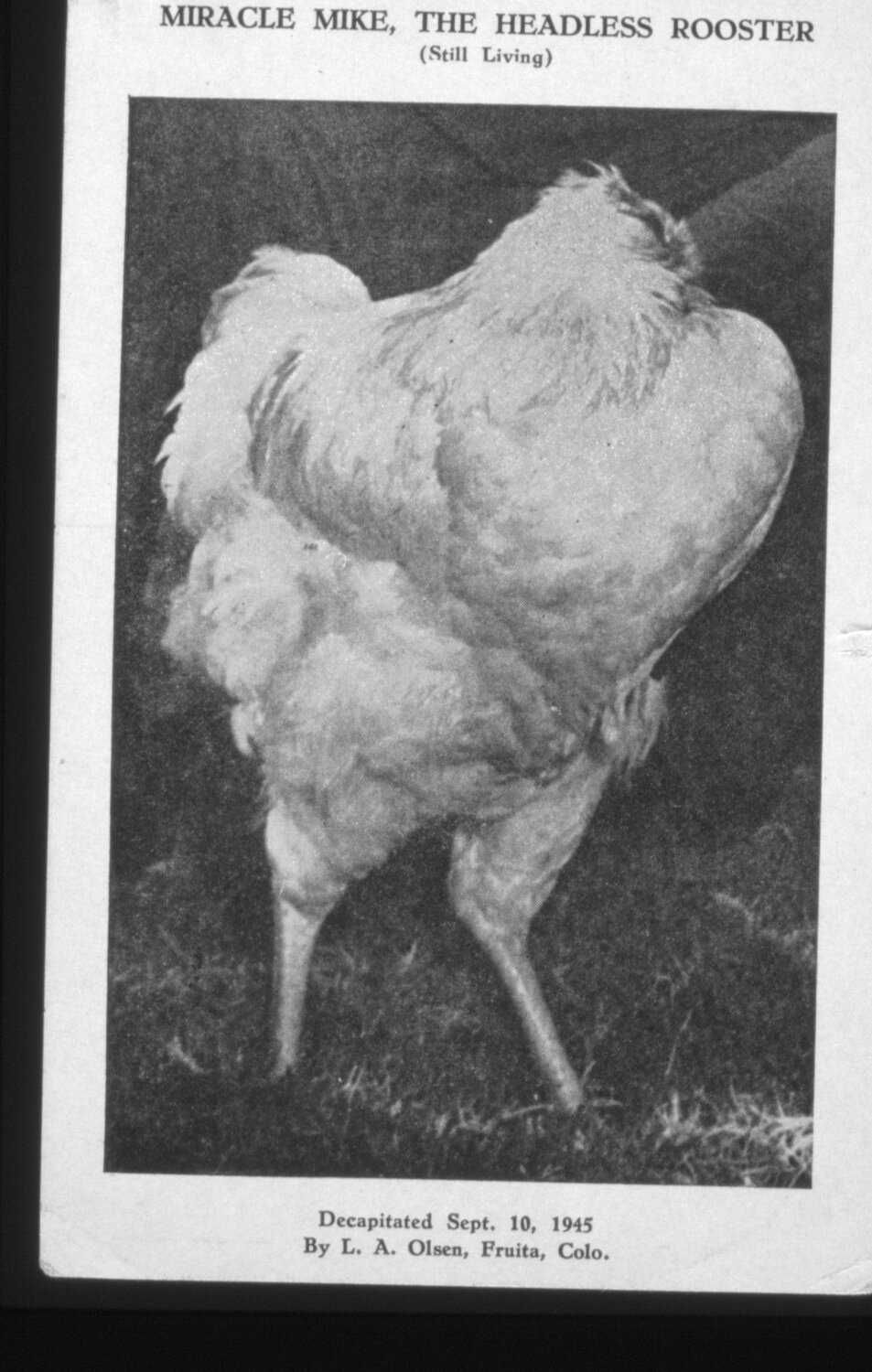

It was a strange scene, to be sure, but not an unexpected one. After all, this was the Mike the Headless Chicken Festival, a celebration of a real-life chicken named Mike who live a year and a half after his owner cut his head off.

In 1945, Lloyd Olsen was harvesting chickens to take into town. He severed the head of one, but inadvertantly left part of the brain stem and one ear behind. This is how Mike lost his head, but kept on living.

The story might seem far-fetched but Troy Waters, a lifelong Fruita resident and Lloyd Olsen's great-grandson, said he has the evidence.

“Sitting up in my house, locked up in my gun safe is all the proof in the world,” said Waters.

The proof Waters mentioned is a scrapbook that his great-grandma Clara put together in the mid-1940s. The book contains articles from publications like Life and Time magazines, featuring the living, headless creature. There are ticket stubs to see Mike, letters from fans and letters from folks begging the Olsens to put the poor creature out of its misery to spare it the indignity of living without a face.

A scrapbook photo of Mike. (Credit: Troy Waters)

The unlikely circumstance of Mike living past his expirationdate brought a lot of excitement to the Olsen family. A sideshow curcuit added the rooster to its roster.. Serving as Mike’s caretaker, Lloyd Olsen saw a lot more of the world than most Fruita farmers in the 1940s. But, due to an honest accident, Mike choked and died after 18 months of living headless.

Maybe Olsen felt guilty about that. Maybe he was uncomfortable with how the Fruita community viewed him after he bought a new truck with some of the earnings from the chicken’s fame. Whatever the reason, Olsen buried the story along with Mike. The scrapbook was shoved into a drawer and the tale faded into Fruita’s past.

A tall tale revived

Steve DeFeyter was known by his fellow members of the Fruita Rotary Club as a teller of tall tales. The stories were meant to elicit laughter at the realization they were all made up. In 1998, however, DeFeyter dug up a real and fantastic story.

DeFeyter would hunt pheasants on a farm owned by John Hutchins. He said if someone wanted to hunt on Hutchins' property, there was a small price to pay.

“You had to spend time with John, sit around a potbellied stove in the wintertime and talk about a wide variety of subjects,” said DeFeyter. Listening to John tell stories was the price of admission. Fortunately, DeFeyter genuinely enjoyed spending time with him. One of the stories John told was that of “Miracle Mike,” a chicken that just wouldn’t quit.

That same year, Karen Leonhart was hired as Fruita’s first full-time recreation director. She was also a member of the Rotary Club. During one of the club’s meeting, DeFeyter brought the story of headless Mike to the group.

“And I absolutely did not believe him,” Leonhart said. “Well, the next week at our meeting, he shows up and hands me a Fruita Times from back in the 1940s that had a picture of Mike on the front cover. And I could not believe it. And there it was right in front of me.”

The railcar that divides

In 1998 some Fruita residents were up in arms about an early 20th century rail car that was going to be placed downtown and used as a landmark attraction.

Sally Edginton was relatively new to the area then. About the railcar, she said, “Oh, my gosh. I was around. It was horrible. It was actually a tempest in a teapot.”

Some thought the rail car was a gift to the city that would revitalize the sleepy downtown. Others saw it as a threat to their livelihoods. An article from that time published in the local Fruita Times describing one of the city council meetings read, “Much of the hour might best be described as a mud-slinging contest.”

“It was a real ‘Parks and Rec’ moment,” Leonhart recalled, comparing the small-town drama to the NBC mockumentary sitcom.

It was during this upheaval in Fruita that Leonhart heard the tale of Mike. The idea came quickly: to have a party in Mike’s honor and create a festival that would unite the town behind a silly cause.

Leonhart said, “I thought something like that crazy local story has got to be something that we could use to help unite our community and maybe [start] thinking of something other than the rail car, something positive.”

An unremarkable start

In 1999 there was an opportunity through Parks and Recreation to apply for a historical grant to fund the festival.

“It was probably $100 or some crazy amount,” Leonhart said. “We thought, ‘oh, we can really have a celebration with this.'”

Karen Leonhart was Fruita's first-ever recreation director.

Both Edginton and Leonhart recall the first festival wasn’t much of an event.

“The first festival was a tub of beer, a guitar player and a food tent that the seniors did,” said Edginton. “The wind came up and blew the tent down, so a lot of us didn't get to eat.”

Leonhart said, “That first festival was definitely an organically grown event, but it was just fun to see people out and having a good time and not worried about other silly things that were going on in the community.”

Waters wasn’t involved in starting the festival but he was in attendance.

Waters said, “Somebody pointed me out in the crowd and said, ‘Hey, that's the great-grandson over there. He worked with Lloyd all the time. He probably knows about it.’”

And he did.

Rediscovered history

When Olsen lost his vision, Waters’ parents bought the farm from him and the family moved into the “old big house” to help take care of him. Waters was a teenager then. In a dresser drawer, he found the scrapbook. It was full of stories he had never heard about.

“My bedroom was next to his [Olsen’s] and sometimes he would wake up and kind of get disoriented where he was,” Waters said. “I would go in and sit with him and get him calmed down and he loved to talk and tell stories.”

“I started asking questions. He was willing to start talking about his days and adventures with Mike that he hadn't talked about in probably 30, 40 years,” said Waters, “His stories were wonderful.”

Troy Waters speaks about his great grandfather, Lloyd Olsen.

By the second year of the festival, national media caught wind of the story and they all wanted to speak with the living relative of the man who cut off the chicken’s head.

In the early days of the festival, Waters was happy to oblige.

“It was kind of fun at the start,” said Waters, “For the first few years, you know, I had people contact me and I did some interviews. CBS Morning News came out to the farm and took pictures of my wife's chickens out back and wanted me feeding them. And, you know, it kind of got silly.”

Waters continued: “I've done interviews, radio interviews as far away as Australia and Holland.”

Later, a Swiss filmmaker made an art film about Mike. The attention got a little out of hand.

Welcomed attention

In the late 90s, Fruita was considered a bedroom community to Grand Junction. Like many small towns at the time, Fruita was begging tourists to come and spend their money — money that becomes pavement for the roads or maybe another full-time police officer. The kind of national publicity Fruita was getting from the story of Mike would resulted in tens of thousands of dollars and the city welcomed it. But every time someone with a camera and a microphone came calling, they wanted to meet Troy Waters.

Each year, as the festival approaches, Waters becomes uderstandably weary as he begins to receive phone calls from various producers wanting to hear Mike’s story — again.

True stories contain nuance. And producers who need to make their trips to Fruita worthwhile zip in and zip out, grabbing the scraps of facts required to tell a funny and cute story. Nuance is lost in the process, and facts devolve into fiction.

Making it right

McKenzie Kimball is the festival director for the City of Fruita. It's a role that couldn’t be conceived of in 1998 when Mike the Headless Chicken Festival was “organically growing” into what it is today.

This year, NPR’s Scott Simon interviewed Kimball for “Weekend Edition.” She was determined to get the facts right because some of them have been wrong for a long time. Maybe the facts don’t matter to the casual listener of this strange tale, but it’s a real story that involved real people: Troy Waters’ family.

What has been fun for the city hasn’t always been fun for the Waters family. The festival grew bigger than anyone ever anticipated and scans of family pictures from the scrapbook started showing up in places that Troy Waters never authorized.

This past year, Kimball was charged with the responsibility of helping to steer the headless chicken in the right direction. Part of that was creating the festival’s first Mike The Headless Chicken history tent.

“I realized the first year that I ran the festival, so few people actually knew what we were celebrating,” Kimball said. “They were just coming to get their kettle corn, run their 5k race, but didn't necessarily know why it existed.”

McKenzie Kimball, left, stands in the history ten with a man who traveled from Denver for the festival.

The tent explained the true story of Mike. It dispelled some of the myths and falsehoods that have grown from previous mis-tellings. And, most importantly, it gave credit and thanks to the Waters family for the true origins of this fantastic story.

“And so it was like, let's celebrate this weird thing,” said Kimball, “and let's try to make sure that this family feels like we're doing it in a way that honors their history and gets some of those things clarified that maybe have been rumors and myths for a long time.”

In future years, Kimball hopes the tent will grow in prominence in a festival which for all intents and purposes resembles just about any other small-town festival with vendors selling shirts and trinkets; food trucks frying anything that can be fried. But, what this festival does have that others don’t is a Peep-eating contest and a very strange mascot of a chicken with no head walking around and greeting children.

At its roots, the Mike the Headless Chicken Festival is the result of a genuine desire to unite a community with some simple and silly fun.It has been meeting that aim ever since.

Leonhart has always enjoyed the metaphor that Mike represents for the little town of Fruita — a town that, for many decades, stood in the shadow of its neighbor, Grand Junction. Mike kept going, against peculiar and difficult odds. Like the little engine that could. Like the Energizer bunny. Like a chicken with his head cut off.

“I mean, I've always said that we can do things here in Fruita that can't happen anywhere else,” Leonhart said. “And I still believe that. And yeah, it ties in and really goes back to Mike and his will to live. I think that's the energy that Fruita has.”

Cullen Purser is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS, reporting from the Western Slope. You can reach him at cullenpurser@rmpbs.org.