Memories of Los Rincones

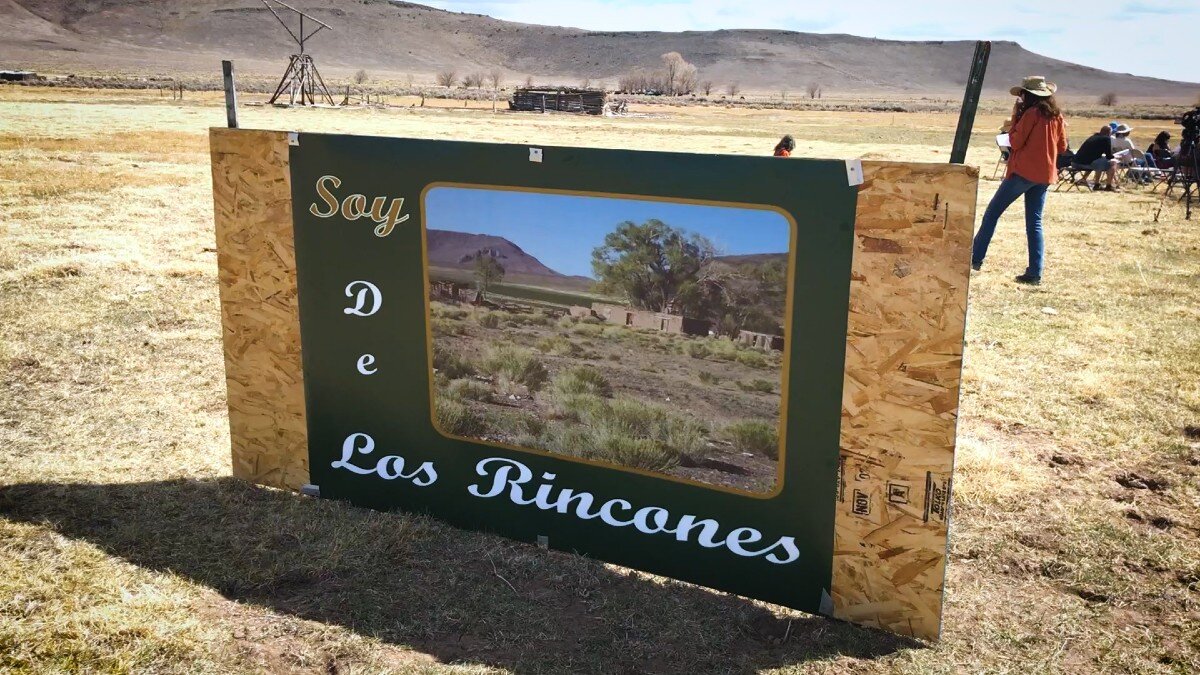

LOS RINCONES, Colo. — A sign stands in a cow pasture on the flood banks east of the Conejos and San Antonio Rivers near the state’s southern border.

It reads, “Soy de Los Rincones.” I am from Los Rincones.

Descendants of what may be the state’s oldest settlement in what is now Conejos County gathered on a beautiful San Luis Valley spring day to share genealogy, history, and memories.

The community, three miles southeast of Manassa, was settled as part of a Mexican Land Grant after Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821. Los Rincones — The Corners, named so because it encompasses a geographic corner of the Land Grant — drew homesteads on what had been wild bison range and Southern Ute homeland, and a trading, hunting, and migration site for indigenous peoples.

By 1870, Los Rincones had 23 residents and a community religious meeting building of Los Penitentes constructed of adobe (earthen bricks) known as a morada.

Several years ago, Joe Mestas, a descendant of settlers of Los Rincones, wished to create an event to share stories, reflecting a local interest in traditions, customs, culture and language.

Working with Manassa resident Loretta Mitson, the two developed a day filled with heritage presentations and site visits. Mestas said he thought “a handful” of folks would show up. On the morning of the event, dozens of people in camping chairs were spread across the field.

Mestas grew up on the ranch lands and hills of the majestic area at around 8,000 feet elevation.

“I have terrific memories of hard work, survival, and learning generally about life,” he said. “This is an awesome place.”

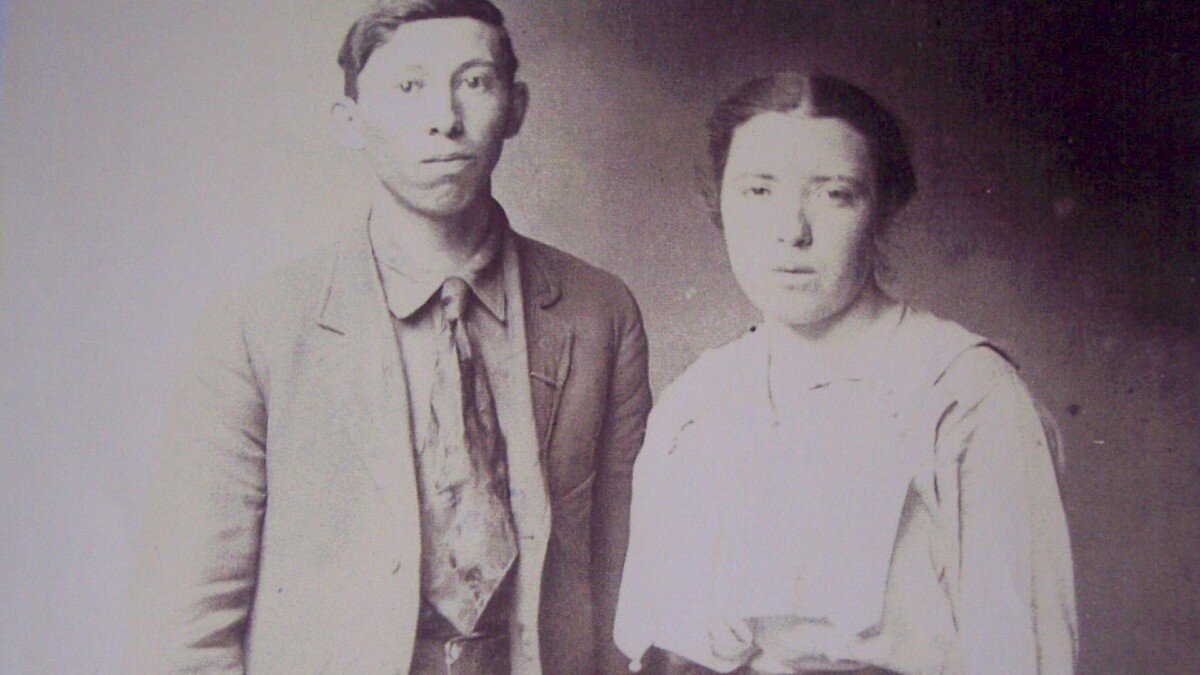

His grandparents, Rosita and Adolpho Mestas, settled in Los Rincones in what eventually became a six-room adobe home in 1921. They lived with two other couples to survive. Today, two walls of the dirt brick home remain in what is now a cattle pasture.

Mestas’ parents, Priscilla and Felix Mestas — his father, a WW1 veteran with the US Army — also lived in Los Rincones.

“They taught me everything I was going to have to know in this world,” said Mestas. “This event is truly dedicated to them.”

LeRoy Salazar, a descendant of settlers of Los Rincones, opened the afternoon with a prayer. “We come together today to celebrate the sacred history of this place,” he said. “We thank you for those that came before us; those that sacrificed, to come here to create a better living for their families, who endured hardship after hardship.”

“They had no indoor plumbing, no electricity, transportation, or very much in the way of health care. Yet they persevered,” Salazar continues. “Today, we honor their sacrifices… and the culture and family traditions that they passed down to their children.”

Mitson said she has been interested in local history since moving to the area in the 1970s.

“I used to tromp through these old adobes with my father-in-law, Henry Salazar,” she said. “He loved history as well. We shared a lot of stories together.”

“What makes this place unique is that it is, if not one of the oldest, perhaps the oldest Hispano settlement in the state of Colorado,” said Mitson.

“But people have been coming through here for at least 13,000 years,” she said. “There are rock shelters and game blinds all through these hills.” The Smithsonian Institution has conducted archeological digs and exploration in the area, Mitson said, finding Folsom spearpoints on the land’s surface dating back 11,000 years.

Ute, Navajo, Apache, and Comanche indigenous groups lived and traveled through the area for centuries before Spanish settlers arrived.

Mitson said Don Diego de Vargas, Spanish governor of the New Spain territory of what eventually became New Mexico and Arizona, traveled through the area in 1692. De Vargas was returning to Santa Fe after years of exile following the Pueblo revolt. Tasked with rebuilding the city of Santa Fe, he met Ute Natives near what would later become Los Rincones, procuring food that would allow Spanish colonists to survive through the winter.

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain, and land grants were established to draw new settlers to the land.

In 1833, forty families were issued the Conejos Land Grant.

“The Conejos Land Grant started south of the San Antonio Hills, all the way to the La Garita Mountains, from the Continental Divide, to the Rio Grande; two and a half million acres,” said historian and retired educator Dennis Lopez.

The land grant called for grantees to homestead immediately, resulting in at least a dozen years of Native American resistance. In 1843, having not yet settled farmsteads, the families of the Conejos Land Grant bound together again to resubmit for the land. After its reissue, they had five years to settle — or lose the land again.

The small community slowly established permanent residency, amid continued standoffs with indigenous inhabitants whose trade routes, migratory patterns, gaming areas, and homelands they displaced.

In 1848, the Mexican American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo turned the land’s ownership over yet again, this time to America. Those living in this Mexican territory were granted U.S. citizenship. The U.S. government stated this land, language, and religion were to be honored intact.

By then, the area’s residents — including indigenous, Native, Mexican, Spanish, and other European peoples — created a complex identity structure still alive and definitive of the peoples and culture of what is now the San Luis Valley.

Mitson encouraged attendees and descendants of the area’s settlers to share their stories during a series of site visits to nearby structures, many now in ruins, and some no longer standing.

Vehicles traveled in a caravan down the long, dusty rural roads from site to site, stopping to reminisce about growing up in Los Rincones. From this area, many leaders have emerged.

Two of Salazar’s brothers, Ken and John, went on to serve in the legislature, John a State Representative from 2005 to 2011 and Ken a Senator from 2005 to 2009, and then, as Secretary of the Interior under President Obama from 2009 to 2013.

In an interview with Pikes Peak Library District in 2004, Ken Salazar recalled his roots.

“I know Los Rincones very well,” said Salazar. “My family still lives on that same farm. My grandmother was born on May 10th of 1884 in the same room where my father was born on March 10, 1916.”

His family raised sheep, cows, and potatoes. “We were a poor family. We didn’t have power lines until 1981,” Salazar said. “It was tough making a living for eight kids under those circumstances.”

Salazar remembers always working on the ranch, even on holidays. Gathering wood by the river, riding and caring for horses, tending to cattle, and putting sheep in pens were common chores. All eight of his siblings went on to become first generation college graduates, Salazar said.

Residents and descendants of Los Rincones plan to continue to meet to share stories of lineage, cultural practices, and local history.

Los Rincones is part of the Sange de Cristo National Heritage area, comprised of Alamosa, Conejos, and Costilla counties. Visit this link for more information on Conejos County.

Robert Bagwell site comments filmed by Keison Morales. Additional photos from Joe Mestas, Eric J Carpio, Valerie Morales and Angelina Navares.