Southern Colorado community works to preserve the memory of historic school desegregation case

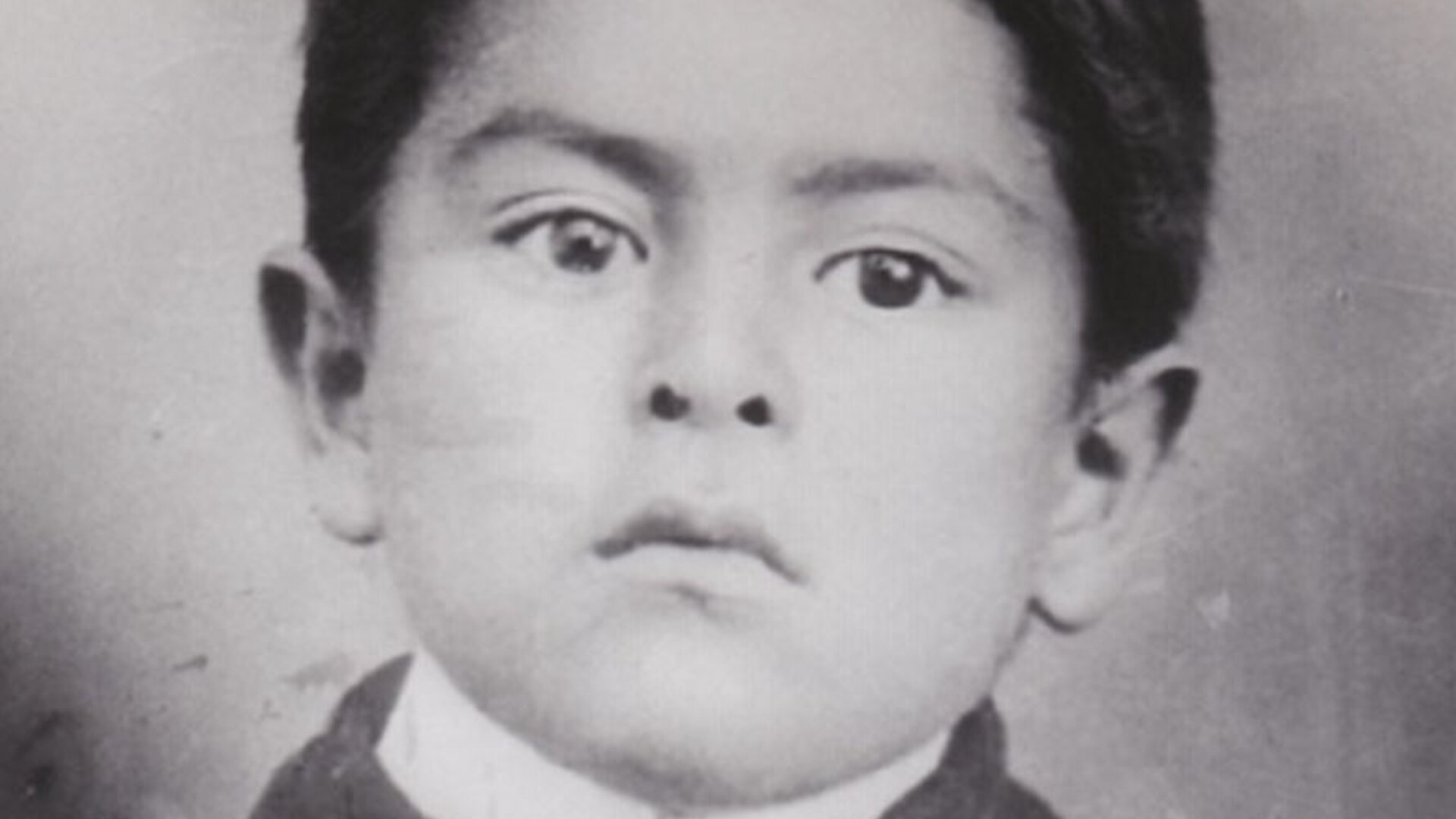

ALAMOSA, Colo. — It was 1912, and 10-year-old Miguel Maestas wished to attend the Alamosa elementary school closest to his home.

The North Side School was just a few blocks away, near the route Miguel traveled each morning and afternoon to the Mexican Preparatory School he attended on the South side of town.

Twice a day, Miguel walked seven blocks to the “Mexican school,” crossing the noisy, busy, dust-filled tracks of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad.

“The town was very much divided by the railroad tracks,” said local resident Katie Dokson of the Maestas Case Committee. “The North side of the town was Anglo. The South side of the town was Hispano.”

Miguel’s father, Mr. Francisco Maestas, was the only head of household with a Spanish surname listed on the North side of Alamosa in the 1911 U.S. Census.

An employee of the railroad, Francisco Maestas knew the dangers of the rail yard first hand. He approached the superintendent and asked to enroll his son at the North Side School.

The request was denied. Francisco Maestas told his son had to stay enrolled in the "Mexican school,” a stout, four-classroom brick building staffed by three teachers with about 140 students. The school was built in 1909 to serve what were presumed to be non-English-speaking children from Spanish-surnamed families.

The case of Francisco and Miguel Maestas would lead to a legal challenge that experts believe was the first Hispanic desegregation case in the United States in which Hispanics won. The case was largely lost to history, but now a team of historians, community members and descendants of the Maestas family are working to ensure more Coloradans know about this important chapter of the state's history.

The San Luis Valley is a cultural crossroads, reflective in its convergence of the land’s many Indigenous, Native American, Mexican, Spanish, and other European settlers.

Prior to Colorado statehood, Dokson explained, an integrated lineage of Hispano and Native American peoples settled the area now known as Alamosa. Around the time Colorado became a state, Alamosa became a major railroad hub, connecting the state’s mining operations and production centers.

“At the time, there wasn’t a lot of communication on weaving cultures together,” Dokson explained.

Many Hispanos in Alamosa — which at that time was still part of Conejos County — were farmers or became railroad workers to adapt to the the shifting economy, said Martín A. Gonzales, 12th Judicial District Judge and chair of the Maestas Case Committee.

“The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo wasn’t that long before this case got filed — some 60 years,” said Gonzales.

Though the treaty assured U.S. citizenship to all prior Mexican residents, “there was a lot of discrimination,” Gonzales said. “The struggle was to become full-fledged citizens — entitled to all the perks, if you will, of citizenship.”

“Which included education,” continued Gonzales.

More than one family went to the district to ask to change their child’s enrollment, said Dokson. “They were kind of brushed away,” she said.

In response, Alamosa’s Spanish and Mexican communities formed the Spanish-American Union, gathering 180 signatures from local parents who wished to desegregate the school district.

The petition was ignored, said Dokson. “But they didn’t take no for an answer,” she said.

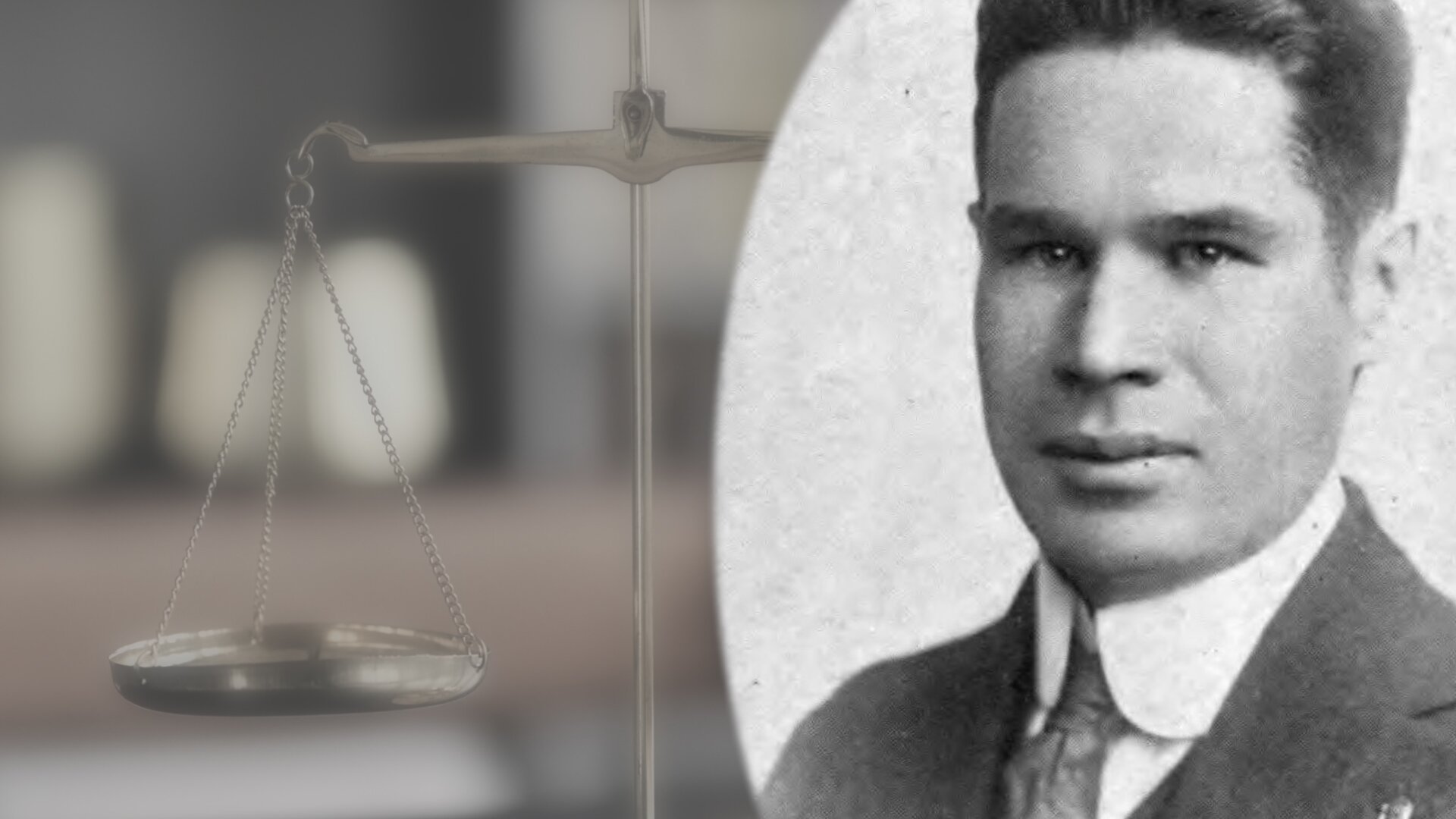

The Union raised money and worked with local priest Father E.J. Montel to hire a young lawyer from Denver, Raymond Sullivan, to legally confront the School District.

The Spanish-American Union was among a number of solidarity efforts and mutual aid organizations, including the S.P.M.D.T.U., that were created to help fill gaps created by inequalities and redlining that were prominent in what had become the Southwest United States.

In 1913, Sullivan filed a lawsuit against the Board of Education on behalf of Francisco Maestas, his son Miguel, and the community who felt they were being treated unjustly. Francisco Maestas et al v. Superintendent George H. Shone and the Board of Education came at the tail end of a long string of attempts to bargain with the school district.

“There was a lot that happened prior to the case itself,” said Dr. Jarrod Hanson, Senior Instructor at the University of Colorado, Denver and member of the Maestas Case Committee. “Parents had petitioned. They had pulled their kids out of school in a boycott to protest what was happening. They had contacted the state superintendent. They had been refused.”

The plaintiffs’ attorney noted that though the area had been part of the United States for over 60 years, distinctions were still being made between “Mexican” and “American” children.

During the case, Sullivan cross-examined school board members and the superintendent.

“One of the school board members said that he did not want to send his own child to a classroom with Mexican students,” said Dr. Gonzalo Guzmán, a Professor at Colgate University and member of the Maestas Case Committee.

“It became clear that, yes, the school board members probably made their decision based on race,” said Hanson.

“The case developed in the context of a culture in which there was a rise of the KKK,” noted Judge Gonzales. “At the same time, there was a rise of Hispanic activism.”

“One of the unique things about the case was how race was being understood and argued,” added Hanson.

The case was filed 17 years after the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld “separate but equal” racial segregation.

Colorado’s own state constitution prevented discrimination based upon race in school, said Gonzales. The school district’s answer to the suit was to argue that Mexicans are white, and thus were not being discriminated against.

“It kind of reserved the typical scenario of how a discrimination suit would occur,” said Gonzales.

“Then you have the plaintiffs push back and say, ‘No, we are Hispanos, we are Mexican, and you are discriminating against us based on our race,’” said Hanson.

“For that to be argued in 1913 was very, very unique,” said Dr. Rubén Donato, professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and member of the Maestas Case Committee.

Donato, Guzmán, and Hanson continued to research the case, co-authoring and publishing their landmark findings in The Journal of Latinos in Education.

Their article found that because people of color were ineligible for U.S. citizenship during the mid-19th century, the federal government categorized Mexicans as white. Classifying Mexicans as white became a political act, because most were racially mixed, the article reports.

“The nuance is that there is no national consensus of where we fit in the racial order,” said Guzmán.

The defense argued the Mexican Preparatory School was created because students spoke Spanish and required English language support. Local newspapers show that students from the Mexican Preparatory School were put on the stand to testify.

“They had an interpreter, and before the interpreter could even finish his questions in Spanish, the students were able to answer in English,” said Dokson.

“The teachers who taught there were saying that they didn’t even teach in Spanish because the students all spoke English,” said Guzmán.

“I think that probably played a big factor in Judge Holbook’s decision,” added Dokson.

In March of 1914, District Judge Charles C. Holbrook ruled in favor of Francisco Meastas and the community he represented.

Holbook stated to the courts that the only way to “destroy this feeling of discontent and bitterness which has recently grown up” between communities of color and Anglo residents “is to allow all children, so prepared, to attend the school nearest them.”

As a former schoolteacher who taught in the South, Holbrook “must have known a lot about race,” remarked Donato.

The Denver Register noted in 1914 that the lawsuit “was the first time in the history of America that a court fight was made over an attempt to segregate Mexicans in school.”

Alamosa’s children were now permitted to attend the school nearest them, regardless of heritage, ethnicity, or culture. It is unknown how many local children were affected, as the Alamosa School District did not maintain its records from this time.

The former “Mexican school” has since been torn down and is the current site of Zapata Park, named for famed Mexican Revolutionary Emiliano Zapata.

The Alamosa School District did not keep a record of this case, said Dokson. “It kind of got lost in the sands of time,” she said.

“I think the reason it got buried is because it was perceived by the Hispanic community as just one more battle — and the battles continue,” said Gonzales. “Yes, it was an important decision. But it wasn’t the end of the struggle.”

The case set a precedent in terms of strategy to take on school segregation, said Donato. “Why did it take over 100 years for this case to finally be discovered?” he wondered.

“None of us were looking for this case. This case found us,” said Guzmán. While researching another topic, Guzmán read an obscure sentence in a newspaper article pointing to the Maestas case.

The article referenced Mexican American residents in Colorado protesting educational segregation — and noted they had filed a lawsuit. Guzmán went straight to Donato.

“I almost fainted. I was shocked,” said Donato. “I, as an educational historian, had never heard of his case before.”

Donato said he immediately understood its implications. “This is really important — not just for the state, but nationally,” he said.

Donato contacted the court clerk in Alamosa County, who in turn contacted Judge Gonzalez.

“[The clerk] said, ‘There are some academics that want access to a file,’” said Gonzales. I said, ‘What file?’ They said it was a 1913 file. I said, ‘Oh my goodness. I don’t know if we can find it. But let’s look for it,’” Gonzales said.

“Lo and behold, we found it,” he said.

The case is unusual because it took place so early on, said Hanson.

“It’s also an interesting part of the country for this case to be occurring in,” said Hanson. “The San Luis Valley has such a rich history.”

“The San Luis Valley was the venue of a large number of struggles,” Gonzales remarked. “The Maestas Case, in my estimation, is the first Hispanic desegregation case in the United States in which Hispanics won.”

“Discrimination still exists,” said Gonzales, who is the first Hispanic District Court Judge of District 12. “Certainly, a lot of progress has been made. And certainly, there is still a lot of progress to be made.”

The Maestas Case Committee — a passionate cast including scholars, genealogists, historians, community stewards and Maestas descendants — are working to assure this early decision in educational equality becomes widely known.

“It may have taken 100 years,” said Ronald W. Maestas, a Maestas descendant, genealogist and retired educator with the Maestas Case Committee. “But we’re finally starting to see the fruits of our labor.”

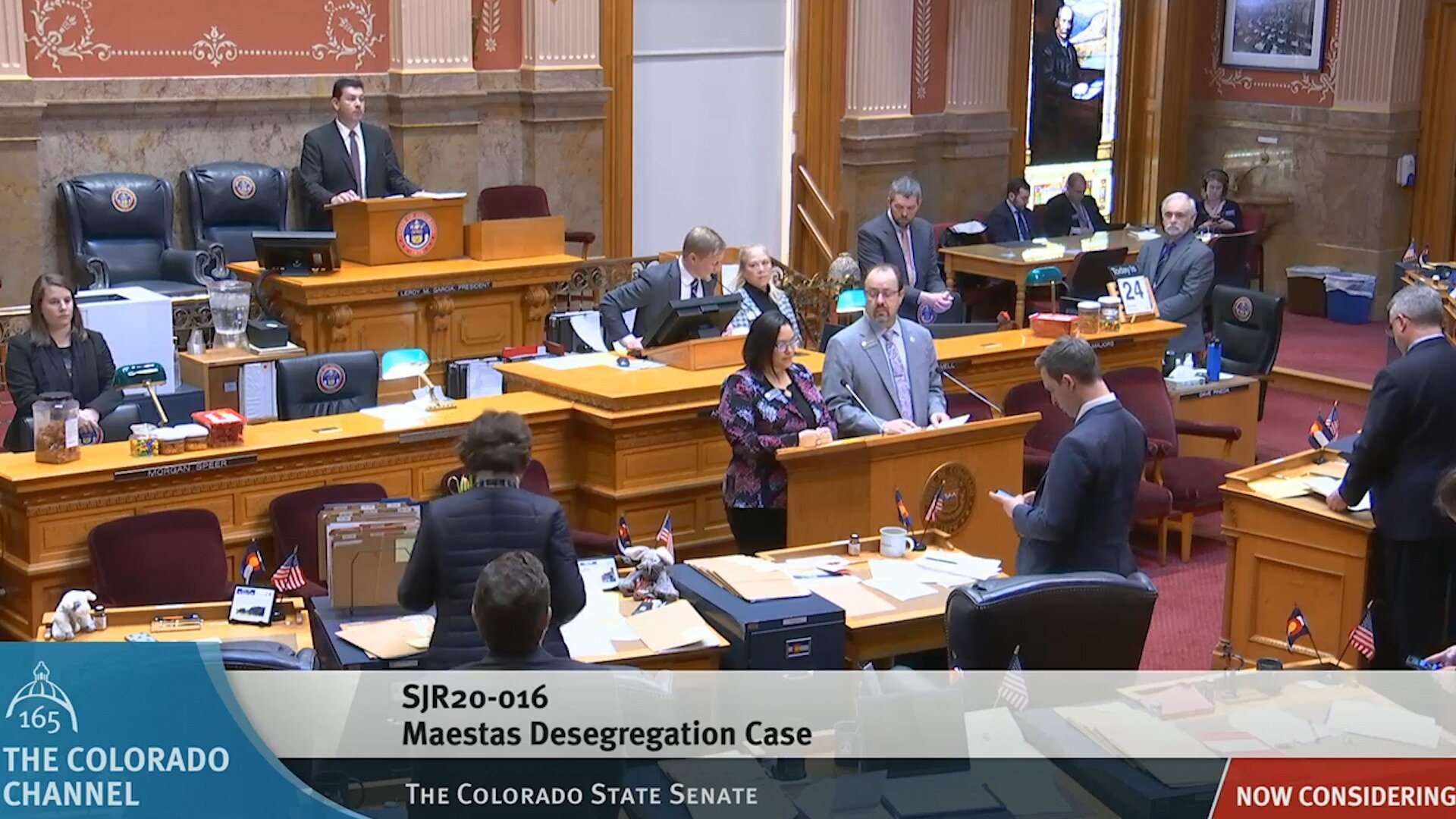

On April 8, 2020, Colorado State Representative Donald Valdez and Senators Julie Gonzales and Robert Rodriguez presented Senate Joint Resolution 20-016 to the Colorado General Assembly in recognition of the Maestas Case.

The Resolution reads: “The nation's earliest and longest unheralded victory in the fight against educational segregation took place in the San Luis Valley between 1912 and 1914 … we, the members of the General Assembly, acknowledge the tireless efforts of the Latino community in advocating for the integration of our public schools and improving outcomes for all students in Colorado.”

The Committee also commissioned a life-sized bronze relief commemorating the 1914 victory to be placed inside the Alamosa Municipal Courthouse. Designed, sculpted, and cast in bronze by Reynaldo "Sonny" Rivera of New Mexico, it depicts two young children. The bronze art was supported with a donation from LeRoy and Rosalie Martínez of Alamosa.

Dokson says the committee hopes the public art work will help raise awareness of the historic decision.

“There are so few landmarks and monuments dedicated to the history of Latinos in the United States,” said Guzmán. “It’s so inspiring to have a monument dedicated to community activism, resistance, and educational rights.”

“I hope that this case becomes part of Colorado’s curriculum,” added Donato.

A commemoration event placing the statue is planned for 2022. To stay updated, visit this link.

“The community was told that they weren’t going to be able to fight this — that no one was going to listen to them,” said Dokson. “They decided that wasn’t an answer they were willing to take.”

“A big takeaway of this story is, don’t give up on hope.”

Kate Perdoni is a multimedia journalist with Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org or on Instagram at @kateyslvls.