'I feel incredibly robbed': The debate and deadly effects of Lyme disease in Colorado

DENVER — Samantha Davis and her 3-year-old son Felix sit together at their kitchen table. A large pile of photographs sits in front of them, and they slowly start to make their way through it.

“Oh my gosh, what are we doing?” Davis asks Felix as she shows him a picture. “Rafting with Papa!” he excitedly responds.

Davis continues to flip through the stack and lands on a picture of her husband wandering through a canyon in Moab, Utah. Her expression becomes somber.

“Here’s Papa in Moab, probably the year he got bit,” she sighs. “We had no idea what the early symptoms of Lyme disease were, or what untreated Lyme could do to you.”

Davis lost her husband Nate Watters on June 5, 2021, to complications from Lyme disease and mold poisoning. He was 36 years old.

“When I look back, he 100% had a bullseye rash on his shin where he got bit,” Davis recalls.

A bullseye-shaped rash at the site of a tick bite is a common early indicator of Lyme disease.

His major symptoms started more than four years ago on a rafting trip near Glenwood Springs. Watters complained that his hands hurt — a symptom easily explained away after a day of rafting and rowing — but the pain never really got better.

“His skin just stopped staying on his hands; his hands turned really raw,” says Davis.

That was just the first of what would become years of confusing and mysterious symptoms. He endured rapid weight loss, swelling in his face, lesions all over his body, extreme fatigue, graying hair, muscle pain and more. Doctors tests Watters for numerous infectious diseases but only one came up positive — Lyme disease.

“The doctor at the time said that Lyme disease isn’t common in Colorado, and so it was probably a false positive and wrote it off,” Davis remembers. “The doctors kept saying to him, ‘This isn’t what Lyme does to people’, and he was like ‘I’ve tested everything, I’ve seen dozens of doctors, I’ve spent thousands of dollars, this is the only thing that has come up positive.’”

A specialist's perspective

Dr. Shawn Naylor sits at his desk in his office at The Sound Clinic, a primary care practice that integrates conventional and alternative healthcare approaches. Naylor founded the clinic in 2008 and has since made a name for himself as a tick-borne disease specialist in Colorado. He’s currently browsing coloradoticks.org — a great resource to learn about ticks in Colorado, he says.

“I’ve always been interested in tick-borne diseases, and definitely tick-borne diseases are an area where the right medical care can be difficult to find because it’s a controversial disease,” says Naylor. “I believe that leads some physicians to shy away from it.”

Lyme disease's controversy among the scientific community is complicated.

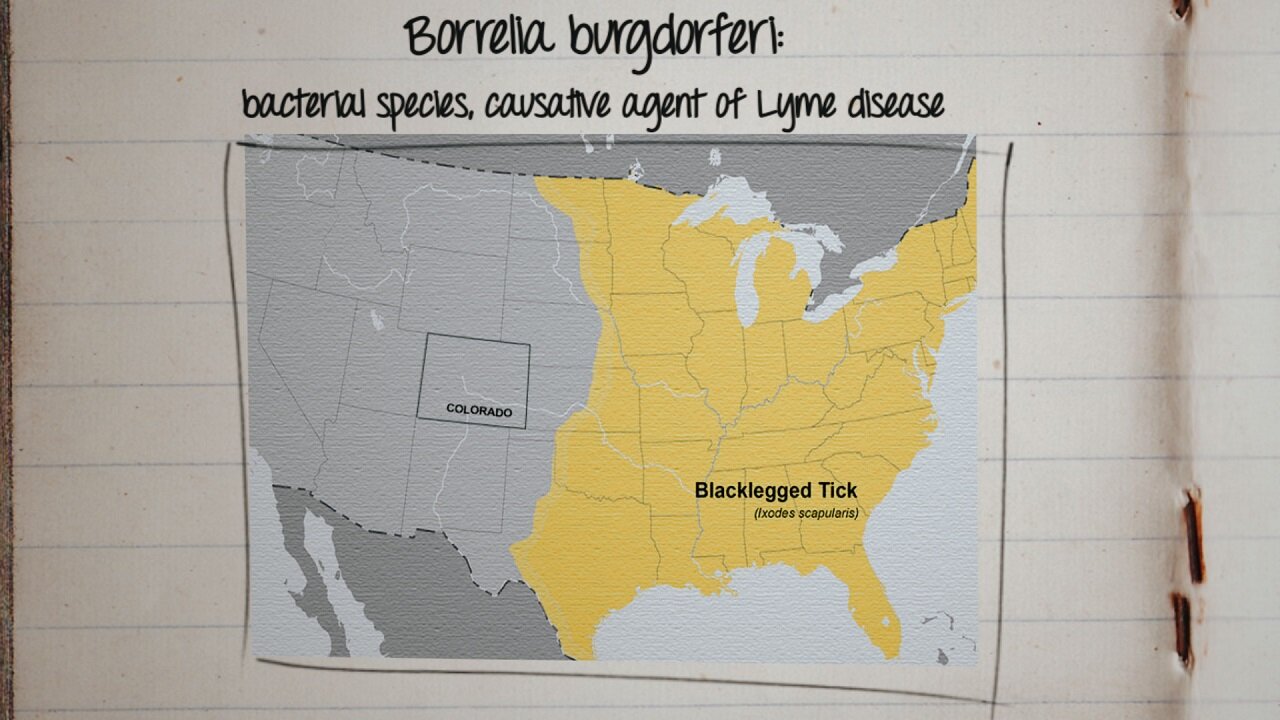

According to the Colorado Tick-Borne Disease Awareness Association, Lyme Disease is a multi-systemic disease caused by infections with a spirochetal bacteria in humans, pets and other animals. It is most commonly transmitted by the blacklegged tick, also known as the deer tick, and is the most common vector-borne illness in the United States. Here’s where things get controversial.

“I think that part of that disparity comes from the fact that different groups aren’t always defining Lyme disease the same way,” explains Naylor. “The bacteria that causes Lyme disease in the strictest sense is called Borrelia burgdorferi. It became technically true to say that there is no Lyme disease in Colorado if you chose to define Lyme disease very strictly as only something caused by Borrelia burgdorferi.”

But a lot of scientists and doctors are defining Lyme disease that way. Most are, in fact.

“Lyme disease is carried by a specific kind of tick, the carrier for Lyme disease does not naturally occur in Colorado,” says Shiran Hershcovich, an entomologist and Lepidopterist Manager at Butterfly Pavilion in Westminster. “So, Lyme disease transmission here is rare to non-existent. It is currently believed that any reported cases of Lyme disease in Colorado are actually coming from visits to nearby states.”

However, some professionals, like Naylor, are embracing a broader definition of the disease, expanded to include new genospecies of the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria.

According to a peer-reviewed research paper published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases in September 1994, a new genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi was discovered in wood rats and ticks found in Northern Colorado.

A second paper published in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology in August 2000 gave the new Borrelia isolate a name – Borrelia bissettii. The strain has been identified in at least three different tick species in Colorado and has been isolated in humans displaying clinical symptoms typically associated with Lyme disease. According to the study, “It is therefore possible that some cases of Lyme disease in the United States may be caused by B. bissettii.”

Naylor speaks carefully on this subject, as if he knows every word he says could be scrutinized by the scientific and medical communities of Colorado. But he also speaks with conviction, believing his view is the safest.

“The notion that there’s no Lyme disease in Colorado, I just think that is dangerous and potentially irresponsible,” he says. “To use [the traditional definition of Lyme disease] is to exclude the possibility that people infected with Borrelia bissettii can get sick. That unfortunately isn’t the case. There are Lyme-like diseases, bacteria that are in that family, that can be acquired from ticks in the state of Colorado, which cause similar problems.”

Potentially devastating effects

The danger, Davis says, comes in when doctors don’t take Lyme disease symptoms and diagnoses seriously as in her husband's case.

“A lot of what Nate ran into was denial that Lyme disease even exists on the west coast. He tested positive multiple times on the western blot” says Davis. “In my experience with what Nate went through, doctors want to err more on the side of ignorance than acknowledging that maybe this is something that has been severely under-studied.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that up to 90% of tick-borne disease cases go unreported nationwide which, according to Naylor, can create a dangerous cycle.

“In a state where [Lyme disease] is not thought to be endemic, where because it’s not endemic the reporting requirements are much more complex and arduous, that becomes kind of self-fulfilling prophecy where in areas where it’s not endemic it doesn’t become endemic – even if it is.”

[Related: Major test of first possible Lyme vaccine in 20 years begins]

The controversy and lack of understanding surrounding Lyme can have a real-world impact on some patients here in Colorado.

Davis is now left with the devastating effects of Lyme disease which, together with mold poisoning, worked to attack and suppress Watters’ immune system to the point that it allowed the infection to take over and eventually take his life.

“The hardest part with him gone is Felix,” Davis says. “The moment [Nate] found out he was having a son was just the most joyous moment … he had big plans for them, he wanted to do overnight fishing trips with him, and so I think the heartbreak of Felix being so young and he’ll never get to know Nate and Nate will never get to have that experience … I feel incredibly robbed.”

While Watters’ case was rare, it was not impossible. Davis hopes that by sharing his story others in Colorado will start to take the disease more seriously.

“By sharing his story and suffering, I hope people realize how serious [Lyme disease] can become.”

Alexis Kikoen is the senior producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alexiskikoen@rmpbs.org.