How one woman grappled with racism after finding out her grandfather was in the KKK

BOULDER, Colo. — History Colorado’s recent release of the Ku Klux Klan’s Colorado ledgers this past April might have shed spotlight on the state’s racist past, but for some, like singer-songwriter Lisa Marie Simmons, discrimination towards people of color has all but left the Centennial State.

While the ledgers published by History Colorado list the names, home addresses, and businesses of Klan members living in Denver during the 1920s, Boulder County had its own local chapter of white supremacists.

Lisa Simmons’ grandfather was a part of that chapter.*

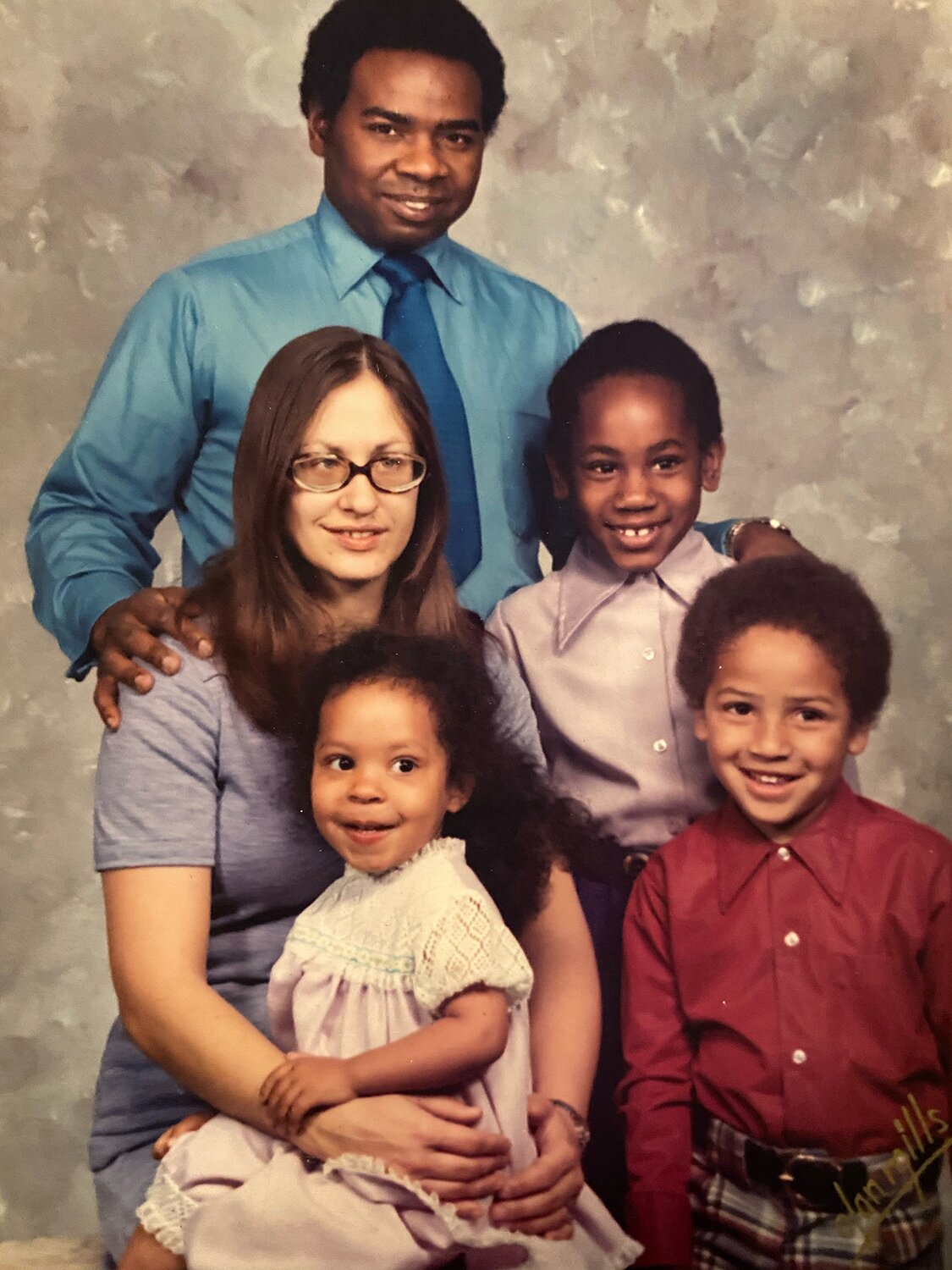

Simmons, who identifies as Black, was born in Colorado Springs but was given up for adoption at birth. Her first family, which Simmons says was in the military, took her to Malaysia where she was allegedly abused and neglected by them before they gave her back.

“There were cigarette burns on my body and I was malnourished when I got back and my hair was falling out,” she recalls. “They ended up putting me on a plane with a note in my pocket.”

Upon returning to Colorado, Simmons was introduced to Boulder residents Arthur and Elaine Simmons, her new adoptive parents. “The family lore, the family legend is that my adoptive mother was so moved and felt this instant need to meet me,” said Simmons. She remembers her mother, who Simmons claims later abused her saying, “‘I've always been your mother and I'm sorry it's taken so long to find you.’”

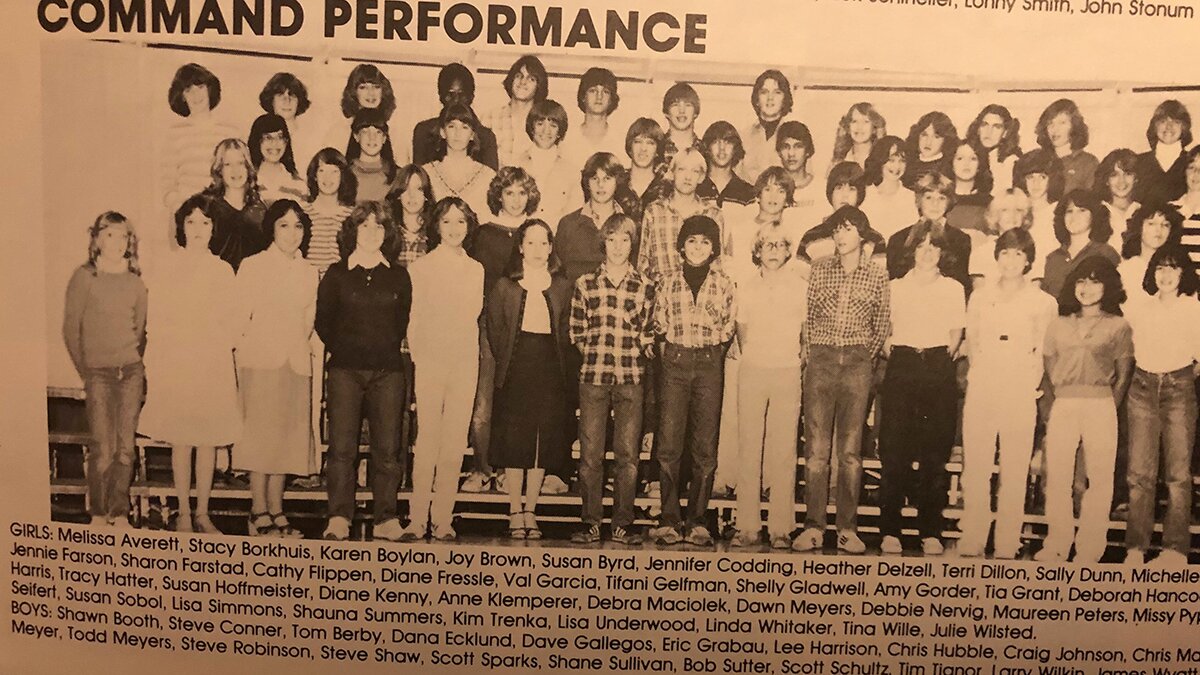

From eight years old to when she left for college at 18, Simmons, along with her adoptive siblings, navigated living in Boulder’s almost exclusively white community where her sense of belonging was often skewed. As a young girl, Simmons struggled with her identity and understanding of what it meant to be Black in the United States.

“Boulder was the most beautiful place for someone to grow up in the 1970s,” the 55 year-old, singer-songwriter, poet, and essayist says. “But when I was growing up there, even today, it’s an overwhelmingly, predominantly white community.”

Boulder, which is 90 percent white, was even less diverse when Simmons was growing up in the mid 70s, after the height of the civil rights movement. During that time, she experienced covert and overt racism regularly.

“One of the things that stays with me growing up there is how othered I began to feel when I was in the last years of elementary school,” Simmons said. “I started having friends telling me N-word jokes.”

Simmons recalls one of her classmates at Eisenhower Elementary School repeatedly hurling racial slurs at her at school until she finally confronted him. Simmons believes her classmate probably learned this kind of behavior and language at home.

“If my grandfather was in the KKK,” she says, “then how many other of my classmates and the other people that I grew up with had family members in it? I mean there were lodges in Broomfield and in Boulder...all over.”

She continues: “You cannot tell me that there were not a lot of other kids in school in Boulder that have family with those ties.”

Simmons confirmed her family’s connection with the white supremacist organization long after her grandfather, Wilbur Gossert, had passed. According to her aunt, Amanda Buchanan, Gossert belonged to the KKK and carried a membership card with him and spoke casually about the organization. His wife, Annetta, also made openly racist comments about people of color, often calling “good Blacks” the ones that “knew their place,” Simmons says.

“It was really normal,” she says, referring to the discriminatory behavior of her family and others in the community.

Looking back, Simmons speculates why members of her family struggled with racism and how the same prejudices show up today.

“I think the white fragility and white fear that we're sort of dealing with now was an impetus for that kind of rationale for that kind of behavior,” Simmons says. “And the frightening thing is that we can find some comparisons between then and now because I think really that's what that stemmed from.”

Now residing in a small town off Lake Garda in Italy, Simmons draws inspiration from her past and channels her trauma into her creative work—using her experience to bring a sense of importance to issues people (especially people of color) are grappling with.

“I've got a poem called ‘Hair’ which is one that stands out to me...it was my first published poem,” she says, “and it was about trying to get my hair done in Boulder.” When she was in elementary school, her mom took her to at least four salons throughout Boulder to straighten Simmons’ hair, which ultimately ended up burning her scalp. At the time, there were no Black salons in Boulder.

The topic of hair is something many Black women can relate to, according to Simmons. “What I really tried to do is to find something universal in my personal experience,” she says, “something that can speak to a wider narrative, and not just to myself.” For Simmons, the best way to reach people is to dig deep within herself. She also found writing to be a great way to process her trauma.

While Simmons returns to Boulder occasionally for work, the artist feels more comfortable in her small town in Italy—despite its lack of diversity.

“Boulder purports to be this liberal, modern sort of little utopia, and it's so not true and it's really frustrating,” Simmons says, who recently attended a conference in Boulder where she experienced microaggressions. “I must admit that I spend less time calling people out just because I'm there to work and concentrate on that. And maybe it's also just falling back into what I was used to doing in Boulder and just trying to make people like me...but I honestly can't imagine living in Boulder today because of that.”

Now, Simmons feels like she can make more of a difference in Lake Garda. “I don’t let anything slide, zero. Anything that anybody has to say that is a microaggression, I will call them out on,” she says.

As the rest of the country grapples with race-based issues, Boulder is not unique in its struggle to attract and accommodate people of color. And Simmons hopes residents will continue to unlearn biases and work on themselves to make Boulder a beautiful place to live for everybody.

“Unless we talk about it and bring it into the open— which is why I'm so glad that they're publishing the records of the KKK — because I think without confronting that past, there's no future.”

*Simmons’ grandfather’s name was not listed in the published ledgers.

Victoria Carodine is a digital content producer for Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at victoriacarodine@rmpbs.org.