175 years after its signing, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is on display in Denver

DENVER — For the first time since it was signed 175 years ago, the scripted parchment pages of the original Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were welcomed to Denver.

Last month, three delicate sheets were put on display as part of an ongoing Borderlands of Southern Colorado exhibition at the History Colorado Center. The parchment pages traveled to Colorado on loan from the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

“There are seminal documents that help to explain how our nation came to this moment in time,” said Jason Hanson, chief creative officer and director of interpretation and research at History Colorado. “This is one of those documents.”

During a time when the land was still primarily inhabited by Indigenous peoples, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed between the United States and Mexico in 1848 to end the Mexican American War (1846-1948). “The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had a number of impacts,” Hanson said, “but far and away the most notable was that it moved the border south from what had been a previous border between Mexico and the United States.”

Overnight, 525,000 square miles of ground and over 100,000 Mexican citizens became part of the United States. “This led to the sentiment that you still hear today: ‘I didn't cross the border. The border crossed me,’” Hanson said. “This document has shaped the lives of people here today in real ways and shaped their family’s stories.”

Aaron Abeyta, an educator, poet, and seventh generation resident of Conejos County and the Conejos Land Grant, said, “The communal land was not recognized by the United States government. Those stories were right there at the dinner table.”

Abeyta said the oral traditions he was raised on “were not anything from fairy tales or books or fables.” Instead, he grew up on “stories about sheepherders, land loss, civil rights, activism, and about fighting for survival,” he said. “Those stories shaped who I am as an adult.”

Abeyta’s family lost land during the aftermath of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo as English-only regulations were posted and a stringent campaign of homesteaders and speculators tore Mexico’s land grants from the hands of citizens.

Stories from his elders “were meant to teach us,” Abeyta said. “The original settlers that came to this part of the Valley were residents or citizens of Mexico. They lost all this land; they lost all this water.”

Some relatives said “lost,” and some used the world “stolen,” Abeyta noted.

[Related: 'Pleas and Petitions': Southern Colorado’s historic struggle for representation]

“By taking the land, you don't just take away land,” Abeyta said. “The loss ripples out to all aspects of life. When you take away the land, you take away the history, the language, the stories, the legends. All those things go with the land. They're inextricably linked. But when you remove the foundation, which is the land, then those other things suffer.”

This change in systems included a shift from publicly stewarded to privately held landholdings. “When your way of life and communal ownership is stripped from you, now it's individual survival as opposed to communal survival,” Abeyta said. “This system has never been for the original inhabitants, whether that is the Indigenous people or the pobladores that came after them. The system has always been for those in the position of power.”

175 years later, the effects of the Treaty are still tangible, Abeyta said.

“If you have any sort of senses at all and you walk into our community, you can see the loss,” he said. “You can see what's transpired because of what's been taken.”

Those most affected by the status of the Treaty “aren't represented the way that they should be,” Abeyta said. Within a dueling consciousness between representation and silence, “The borderlands exist within each and every person,” he noted.

Dawn DiPrince, Executive Director of History Colorado, said it is important to “remember that human hands made this document. And even more, you must remember that the human-forged conquest, in terms that moved international boundaries and disrupted lives, also founded this document. Please remember those ancestors, including the ancestors of many of you in this room today, whose lives were changed forever.”

Abeyta said he is grateful to have maintained his history despite generations of attempted erasure. After the Treaty, “all these other things followed: Poverty and loss. Educational systems suffered; economic systems suffered. Language systems suffered,” Abeyta said. “I am blessed, honestly, to know about some of these things so that we can understand the genesis of the pain and suffering of our community.”

As an educator, Abeyta teaches students “how to circumvent that history by knowing what it is. We can either plow through it with our own education, with our own strength and our own power. Or we can avoid it altogether and create a new system.”

Kate Perdoni is a Senior Regional Producer with Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.

Related Stories

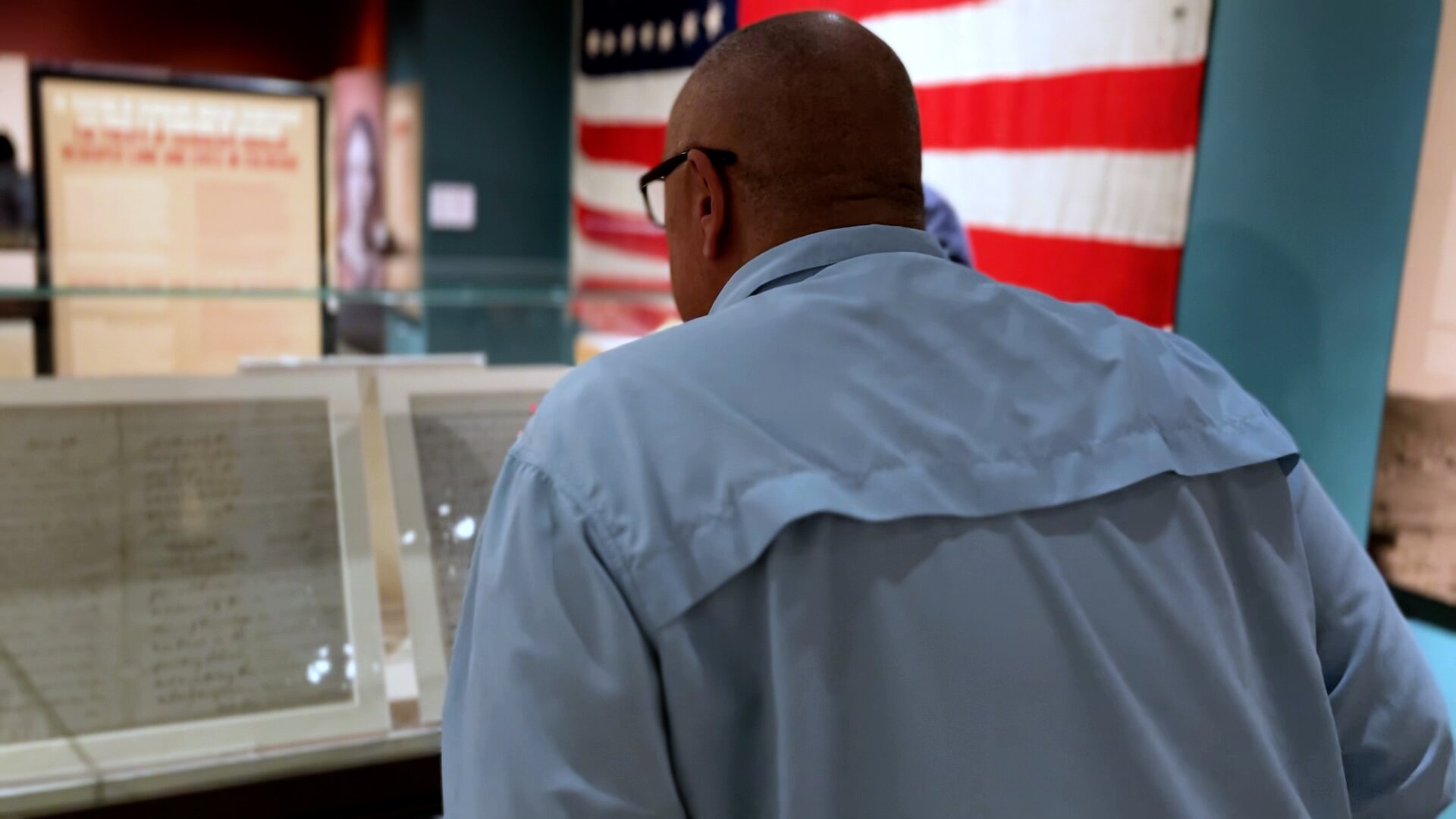

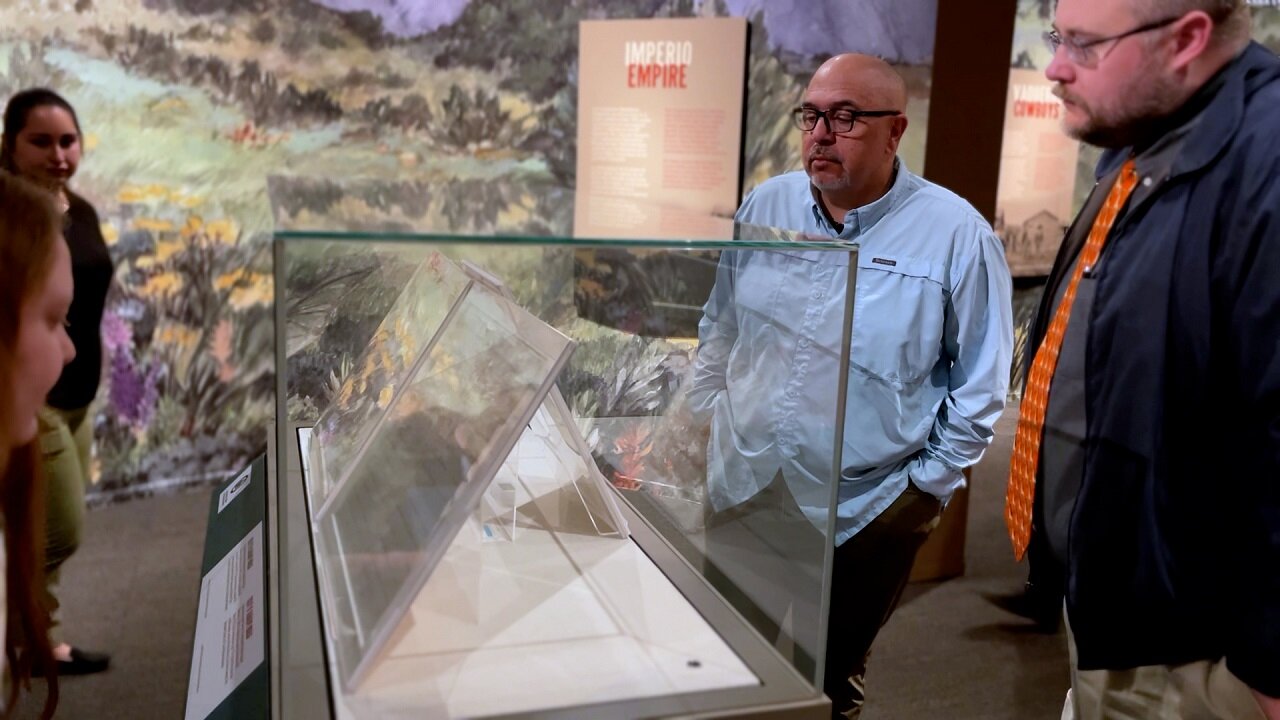

Aaron Abeyta, whose family was personally impacted by the border moving as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, looks at the Treaty for the first time as it is unveiled to the public at the History Colorado Center.