Activists reframe food inequity as ‘Food Apartheid’ to find new solutions

COLORADO SPRINGS,Colo. — Food justice is a passion for Patience Kabwasa, the executive director for Food To Power, a nonprofit that provides groceries and food education classes to low-income people living around Colorado Springs.

Kabwasa works in the Hillside neighborhood that borders the Middle Shooks Run neighborhood and the downtown neighborhoods of Colorado Springs. These areas are classified as a "food deserts," where neighbors struggle to access fresh produce, accourding to the Environmental Research Institute.

Kabwasa lives near Palmer Park, where the closest grocery store is a Walmart, a little more than 2 miles away. She uses rideshares or rides from friends or family to get her groceries.

“When I think about a desert, or I think about communities that live in a desert [and] when they have access to the land and resources, and they’re able to move on that land where those resources are to sustain themselves. They are adequately able to sustain themselves,” she said.

Kabwasa and other activists say “food apartheid” is a more apt term for describing the experience and consequences of having inadequate access to nutritious food.

“I think that language is important to really get at the root cause of why people are in the free-food-line in the first place, and really address those causes,” she said.

Kabwasa said the term “food desert” is harmful because it makes it seem as if not having access to fresh food is a naturally occurring phenomenon — like a desert landscape — rather than the result of political and social choices.

“Food apartheid” emphasizes the deliberate and systemic inequalities in food access, which are often rooted in historical injustices such as redlining, segregation and discriminatory economic policies, according to Karen Washington, a food activist who first used the term in the 1980s.

It highlights how specific communities, particularly those inhabited by people of color and low-income residents, are systematically deprived of access to healthy food options.

“Using food desert is offensive to many people who come from and grow foods in the desert. It’s not an accurate term,” said Fatuma Emmad, co-founder and head farmer of Frontline Farming, an urban agricultural food justice organization led by and for people of color. “One of the greatest weapons of capitalization is abstraction.”

[Related: Food To Power: Cultivating food access]

For Colorado Springs resident Bernice Mulvihill, the terms “Food Desert” and “Food Apartheid,” don’t ring a bell, nor do they make her think about her proximity to a grocery store.

“Most people I know don’t live within a mile of a grocery store,” said Mulvihill.

Mulvihill said it takes about a mile just to get out of her neighborhood, Security-Widefield. Then she drives about 5 miles to the nearest grocery store. Typically, she can only shop when her son can drive her.

“Those terms don’t draw my attention and wouldn’t cause me to investigate what they even mean,” said Mulvihill.

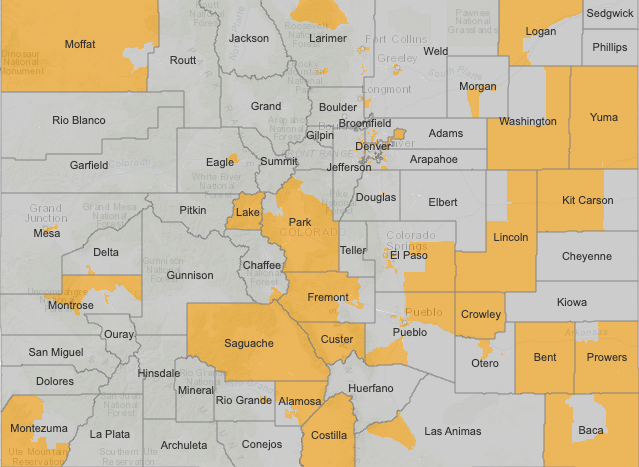

The Environmental Systems Research Institute identifies many Colorado communities as food apartheids, including Denver neighborhoods Montebello and Westwood, and the cities of Pueblo, Alamosa, and Aurora.

Aurora, Colorado’s third-largest city, has food apartheids in its north and central neighborhoods.

This map from the Enviromental Research Institute indicates Colorado food deserts with the areas highlighted in gold.

Kabwasa said part of her advocacy is generating an understanding around the existence of food apartheid to help find different solutions.

Food apartheids often go hand-in-hand with "food swamps," which Kabwasa defined as areas with an overabundance of fast-food chains, convenience stores, and other sources of unhealthy, highly processed food.

Fillmore Avenue in Colorado Springs exemplifies a food swamp, where fast-food restaurants and convenience stores line the street.

Kabwasa said Fillmore Street in Colorado Springs was an example of a food swamp, where the main thoroughfare is lined with convenience stores and fast food, high-calorie options.

Photo: Lindsey Ford, Rocky Mountain PBS

Antolina Medina, a mother of two boys, said she lives in a food swamp in the Lowry neighborhood on the border of Denver and Aurora. She said she spends 70% of her income on rent and rideshares, or paying a neighbor to give her a ride to the grocery store.

“In my opinion, everyone should have access to fresh and affordable food because it’s a human right. The same goes to having access to clean water and air,” Medina said.

Another barrier for Medina is that she must go to the grocery store two or three times a week because if she buys a large amount of produce at once, it will rot and go to waste.

“I make sure my kids have healthy food available," she said. "When we as a community don’t have access to healthy food, we are creating a generation that is not going to be able to live long lives, or they will have to grow up too quickly. It’s hard to have a childhood when you don't have the right foods to nurture your brain."

People who live in food swamps can more readily access high-calorie, low-nutrition foods, and their food choices are compromised by lower incomes and transportation access, Kabwasa said.

So, residents have plenty to eat but are not very well-fed. Over time, lack of fresh food access countered by an abundance of easily accessible junk food contributes to poor dietary habits and health outcomes.

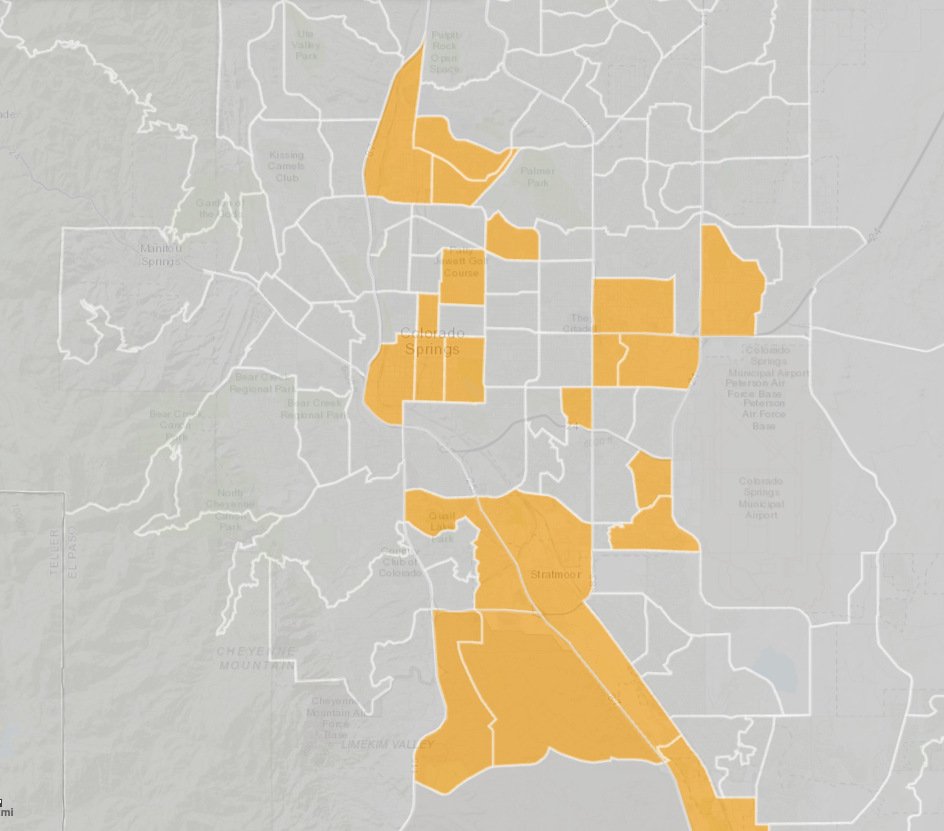

The highlited gold areas indicate communities idenfitied as a food apartheid in and around Colorado Springs.

Credit: Enviromental Research Institute

In order to combat some of the negative outcomes of food apartheids and food swamps activists such as Thai Nguyen, who founded Kaizen Food Rescue in Denver to establish food shares among immigrant communities, focus on culturally responsive food justice.

Nguyen and volunteers locally source traditional foods that food pantries may overlook. For example, during Ramadan, Kaizen sourced Halal foods such as specialty onions and turmeric, which Nguyen said are hard to find in the free food line, for Iftar meals.

“We are empowering communities," Nguyen said. "Awareness of food advocacy is crucial to fostering empathy and solidarity in communities that are marginalized and under-resourced.”

Lindsey Ford is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Lindseyford@rmpbs.org.