Drought and newcomers threaten Southern Colorado's traditional water systems

COSTILLA COUNTY, Colo. —In the 1840s, Mexican and Spanish agrarian settlements brought to life an acequia tradition that still remains in what is now southern Colorado.

Acequias, an irrigation system of hand-dug ditches, divert water from natural streams from nearby canyons to irrigate long plots of farm and grazing land. The acequia system allows each landowner equal access to water.

The system depends on gravity, working with the sloping dry, desert landscape of the valley to flood-soak crops, gardens, and provide drinking water for livestock.

Acequias were first brought to Spain by the Romans and the Moors, and came to what is now southern Colorado with Franciscan missionaries and Spanish settlers.

In the small Colorado village of San Francisco and its surrounding villages, the original acequias are still operational and are often maintained and used by descendants of the first settlers of present-day Colorado.

Related Stories

"We’re a land and water based people. I am a Chicana, I am a child of the corn. My parents were farmers,” said Junita Martinez, a parciante (water-rights holder) and irrigator on the San Francisco Acequia. Her husband, José, was born in San Francisco. José’s lineage goes back to the initial settlers of the community.

In this village, named after Saint Francis — the patron saint of animals and ecology — water is life.

“It gives us what we need to live. It grows our crops,” said Martinez.

The property’s main aceqiua, an offshoot of San Francisco Creek, begins in San Francisco canyon about four miles from their home, Martinez explained. Springs made of snow melt eventually pool into the small beginnings of the creek. This same stream widens further down the mountain, then diverts into ditches that reach into each field. An elegant system of hand, and now machine-dug waterways, feeds the whole landscape.

“These acequias were created by hand — by folks who just had an axe, a shovel, and a plan,” said Martinez.

At over 8,000 feet in elevation, each of the nine local canyons provide a water source to surrounding Rio Culebra Watershed communities. Today, over 240 families irrigate more than 24,000 acres here, many using traditional acequia irrigation practices. These families grow traditional crops like corn, peas, potatoes, and beans adapted to the high altitude, dry climate, and short growing season.

“Currently in our community of San Francisco, about 60 households in the village irrigate 1,062 acres,” Martinez said.

Martinez herself grew up on Denver’s West Side, living in three separate housing projects. The properties are now all developments. She remembers that everything was made of heavy-duty cement. “Even the sink area was made of cement,” she said. “The stairs, the floors. Everything was cement. It felt like a prison.”

She graduated from West High. Her parents were from different villages in the small Gallinas Valley in New Mexico. Her father, a veteran, drafted in World War II, had nine siblings, and her mother had eight. “We were always visiting cousins and traveling back to New Mexico,” she said.

That’s where Martinez first learned about acequias, and spent time cultivating traditional practices of a subsistence lifestyle still used today. San Francisco and the villages near the Colorado state border identify their culture — including food, art, spirituality, language, heritage, customs, and social sphere — more closely with that of Northern New Mexico, Martinez said.

“I get to experience this every day,” she said, motioning to the acequia and mountain terrain. “These things, you cannot put a value on.”

Life here in San Francisco, she said, is simple. She goes shopping once a week, one hour away. She talks to her friends and family at the post office, catching up about new babies, and what it’s like to lose someone.

“It’s the human touch,” she said. “I also like the fact that it takes effort to live like this.”

Acequias require maintenance, community support and input, and increased education to maintain protections with changing times — and a changing climate. An acequia comisión is voted in by landowners each year, including a President, Treasurer, and Secretary. These elected officials work closely with the Mayordomo, or ditch rider, to keep track of water rights holders, schedule and facilitate water use, and decide how to divvy water in times of drought. Regardless of acreage, each landowner receives one vote.

“We get people from bigger cities, and they buy a huge ranch, and then they’re a little bit miffed and upset because their vote is only one vote — just like the gentleman with his little two acres,” Martinez said. “But it’s effective, and it’s survived almost 200 years. I think it’s worth saving.”

Historically, the community has ways of dealing with drought and water scarcity that envelope into part of the local tradition. When a year brings less snow, the community takes action.

“We have a very long tradition that works,” said Martinez. “We’re communal in the fact that the water has to be shared. If there’s not enough water, than our Mayordomo and our Comisión have to figure out who gets water.”

In times of drought, water might be limited to certain days per week, with each landowner receiving fewer turns.

“People cutting down their water levels allows everybody a chance to irrigate,” said Martinez. “Because of climate change and other factors, it’s been so hard. Every year, it gets more difficult because of the scarcity.”

In 2012, there was “a serious, serious drought,” Martinez said. “We lost everything. Nobody grew a bale of hay. There have been times where it's been very, very dry, where actually even the fish in the Creek have died, because there just isn’t enough water.”

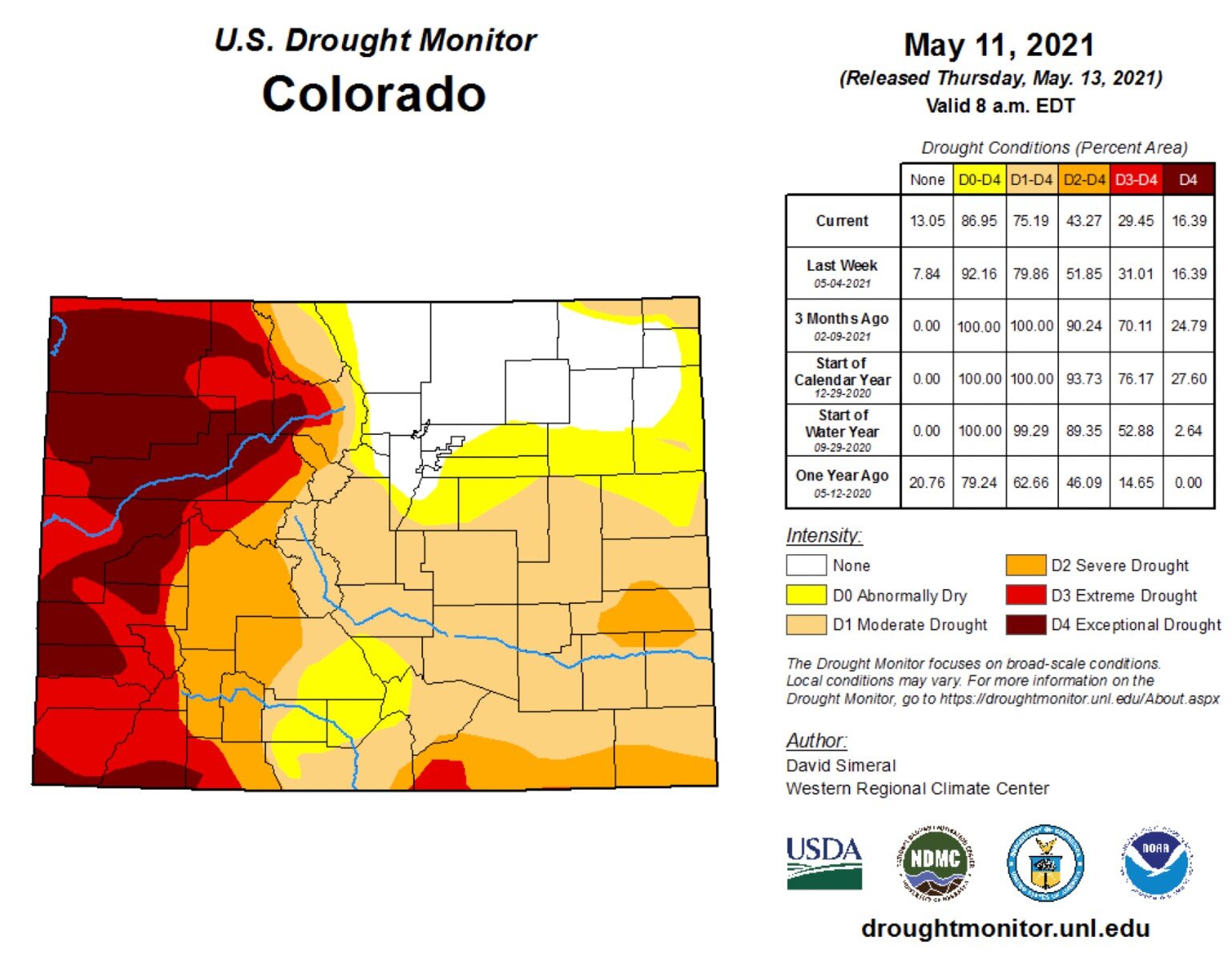

According to the Colorado Climate Center — part of the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University — San Francisco canyon is currently experiencing moderate to severe drought.

“We’ve had some very serious arguments and hardships concerning our acequia,” said Martinez.

The community can provide education to preserve and sustain tradition but ultimately, “we’re living on the hope that we’re going to get the resource of snow every year, and enough rainfall,” said Martinez. "That’s the hope that springs eternal out of us — that we’ll always have water of some kind coming through.”

Adding to the urgency of maintaining traditional water rights uses are newcomers, some of whom don’t understand the acequia system, Martinez said. Neighbors, vecinos, must all work together for the system to function properly.

For Martinez, it’s no longer about preventing people from finding out about this rich lifestyle — she said that has already happened. Now, it’s about further integrating the practices and beliefs that make this place special so that they are understood and supported by those who are moving to the area.

“I want to hide it. I want to keep it a secret. But I live in the 21st century, and it’s impossible to leave any areas undetected anymore. It’s gone,” said Martinez. “I figure if people enter with a better sense of where they’re coming into, the traditions and the culture, they’ll be more apt to want to protect it, and keep it the way it is.”

“The tradition of being a land and water-based people, of teaching your children that this water is what gives us and our villages sustenance — it’s invaluable,” Martinez said. “It’s something you pass from one generation to another.”

“Then, the next thing is, you have to fight like hell to keep it.”

Kate Perdoni is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.