Distribution of COVID-19 Vaccine Haunted by Tuskegee Experiment

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the development of vaccines to treat the disease, many African Americans have expressed deep apprehensions about receiving being vaccinated.

With more than half a million Americans dead and some 24 million infected with the virus, it may seem peculiar that anyone would decline a treatment that has been hailed by the medical establishment to be as much as 95% effective. However, for African Americans there is a disturbing backstory.

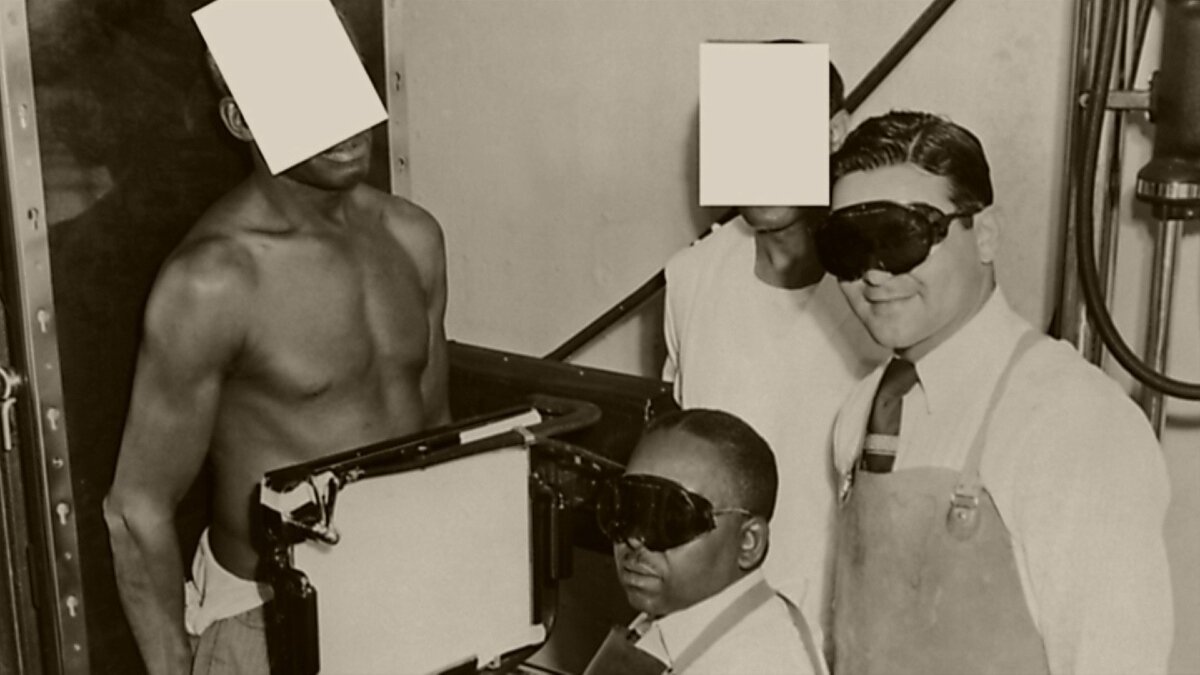

In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) launched what would later become known as the Tuskegee Experiment. It was designed to study the progression of the contagious venereal disease, syphilis. The government deceived unwitting, largely uneducated Black men into participating in the program under the guise of it being a treatment.

More than 600 men, principally sharecroppers and those who lacked access to professional medical care, were recruited from Macon, Ala. Physicians from the PHS told the men they were being treated for “bad blood”—which in those days could have been used to describe a wide range of conditions.

Of the group, 399 of the men reportedly had an underlying, latent case of the disease while a control group of 201 were disease free. Under the observation of health workers, the men consistently received placebos that physicians knew would have zero effect on the condition.

When penicillin became available in the late 1940s, the very same health officials convinced doctors in Macon County to deny the treatment so their studies could continue. They subsequently moved the program to Tuskegee Institute, which is now Tuskegee University, the well-known, historically black college (HBCU) founded by Booker T. Washington.

As the progression of the disease was tracked, health care workers watched as the men died, lost their eyesight, suffered mental and psychological manifestations—ultimately going insane, and experienced other health problems resulting from not receiving appropriate medical care.

It would be more than 30 years before a San Francisco-based disease investigator discovered the program and expressed deep concern over whether it was medically ethical. A committee, formed to review the study in the mid 1960s, determined that the program would continue until all the participants were dead. The analysis of project data was deemed to outweigh the physical well-being of the participants.

Outraged, the investigator leaked the information to a member of the Associated Press, and the story broke in the summer of 1972. The public was infuriated.

An ad hoc panel was assembled by the U.S. Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs to review the study. Comprised of nine members from the fields of law, religion, medicine, education, labor and public affairs, the panel found that the men had freely agreed to participate, be studied and treated. Yet, no evidence showed that they were informed by the researchers of the program’s real purpose. Furthermore, the men were grossly misled and not provided with factual information prior to giving informed consent.

Beyond the lack of transparency or true consent, the men were never provided with appropriate treatment for the condition—not even when an effective treatment became widely available in the 1960s. They were never presented with the option of leaving the study. Based on this lack of opportunity to get treatment when available, the panel concluded that the Tuskegee study was “ethically unjustified.”

The panel also determined that the program’s results were statistically insignificant when considering the risk the program posed to its participants. The results actually showed that the treated men’s life expectancy decreased by 1.4 years. The panel finally recommended an end to the program.

In November 1973, the Tuskegee Experiment was officially terminated. However, 28 of the men had died from syphilis, and more than 100 had passed from disease-related complications. Additionally, more than 40 of their wives were infected and passed it on to scores of their children.

Congressional hearings in 1973 led to an out-of-court settlement of $10 million to the heirs of the participants. It also led to policies designed specifically to protect human subjects in research projects funded by the government.

Not until 25 years later did a government official publicly acknowledge that the study occurred and accept responsibility. In a gesture to promote better race relations, President Bill Clinton issued an official apology for the Tuskegee program, saying, “The United States government did something that was wrong—deeply, profoundly, morally wrong… It is not only in remembering that shameful past that we can make amends and repair our nation, but it is in remembering that past that we can build a better present and a better future.”

Vaccination Fear Founded on Multiple Historic Medical Injustices

Today, the profound injustice of the Tuskegee study is just one historic episode behind the trepidatious attitude of African Americans about receiving a government-approved medical treatment. This community relates more than most to President Ronald Reagan famous words that “the nine most horrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government and I’m here to help!”

Related Story

America’s cultural and medical landscape has had many other examples of historic injustices based on race. After the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865 that freed enslaved Blacks, those who could not accept equal rights for African Americans used science to reinforce racial biases. Some in the medical community engaged in purportedly "scientific" studies to prove white superiority.

Their hypothesis was that African Americans were uniquely fit to be slaves. If they could prove the Black male was physically strong and simple minded with a primitive nervous system, then they theorized that Black slaves suffered from less emotional and mental illness than their free contemporaries so were not impacted negatively by slavery. With this type of scientific reasoning, programs like Tuskegee were bound to be approved and normalized.

Many historic documents show that the majority of medical and scientific authorities of the late 1800s and early 1900s held these unproven notions about African Americans. They advanced the theory that Black men had underdeveloped brains, overdeveloped genitals, a large sexual appetite, and a deep-seated desire for sex with white women.

These unsound scientific beliefs included Black people’s genetic proneness to sexually transmitted diseases. Thus, researchers, and those in government who would authorize their work, devised the Tuskegee program. The PHS justified the Tuskegee project, calling it a necessary “study in nature” rather than an experiment. They suggested that it would be a basic observation of the normal progression of syphilis among people who would not seek treatment on their own.

Macon County was selected due to estimates of high rates of syphilis among its population. The program sought to initially recruit participants between the ages of 25 and 60, who were told that the program would only last six months.

The program initially ran into significant resistance as members of the community did not trust the researchers. Since the men believed that they were receiving the medical attention in order secretly to be drafted into the military. To convince them, the program began to test women and children as well.

The male participants became suspicious, believing that they were being deceived, and stopped keeping their appointments with the physicians. However, during the Great Depression, a good, consistent hot meal was an effective lure. The program even hired a nurse to transport them back and forth to the research facility, and offered to cover funeral expenses when the men died.

When World War II broke out and the men’s syphilis was discovered during their physical exams during army recruitment, the program had them removed from the army to keep them in the study. Even with the passage of the Henderson Act of 1943, requiring public funding of tests and treatment for venereal diseases, the program continued to actively prevent their participants from receiving treatment—an act that was expressly against the law. Despite the researcher’s best efforts, about one third of the participants began to receive treatment anyway.

They continued with the deception through the late 1960s, saying that it was too late for the men to receive treatment. This led the World Health Organization to publish the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964, designed to protect humans from experimentation. Even then, the PHS continued the Tuskegee program.

Finally, after the program’s 1973 termination, the U.S. Congress passed the National Research Act in 1974. The act requires that programs obtain informed consent from study participants, and any research be administered and supervised by Institutional Review Boards both within universities and medical facilities, overseen by the national Office of Human Research Protections.

As part of the 1973 settlement, the Tuskegee Health Benefit Program was launched to provide lifetime health services and burial benefits to the wives, widows and children. In 1995, it was expanded to include medical benefits. Today, the program is housed within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While those strides in human rights are important, the Tuskegee program already created a lasting impact on the level of trust and acceptance in any governmental health program, especially by African Americans. Stories about the program continue to inform decisions about who and where they seek medical services, including whether to be treated by a government-recommended vaccine for COVID-19.

The last Tuskegee test subject passed away in 2004. The spirit of Tuskegee and its negative impact on African Americans’ acceptance of government health programs is still very much alive today, during the worst international pandemic in a century.