Discussing death: How different cultures in Colorado celebrate and contemplate the inevitable

In our episode of "Colorado Voices: Dealing with Death," airing Sept. 8 at 7 p.m., Rocky Mountain PBS explores the death care industry in Colorado.

We look at after-life options and why talking about death is so taboo. There is a lot of mystery surrounding death and dying, but one thing we know for sure is that we can't be sure of what happens when we pass on. As humans, there are thousands of ways that we embrace and contemplate death. Here, we share four different views, from four different cultures, on what happens when we die.

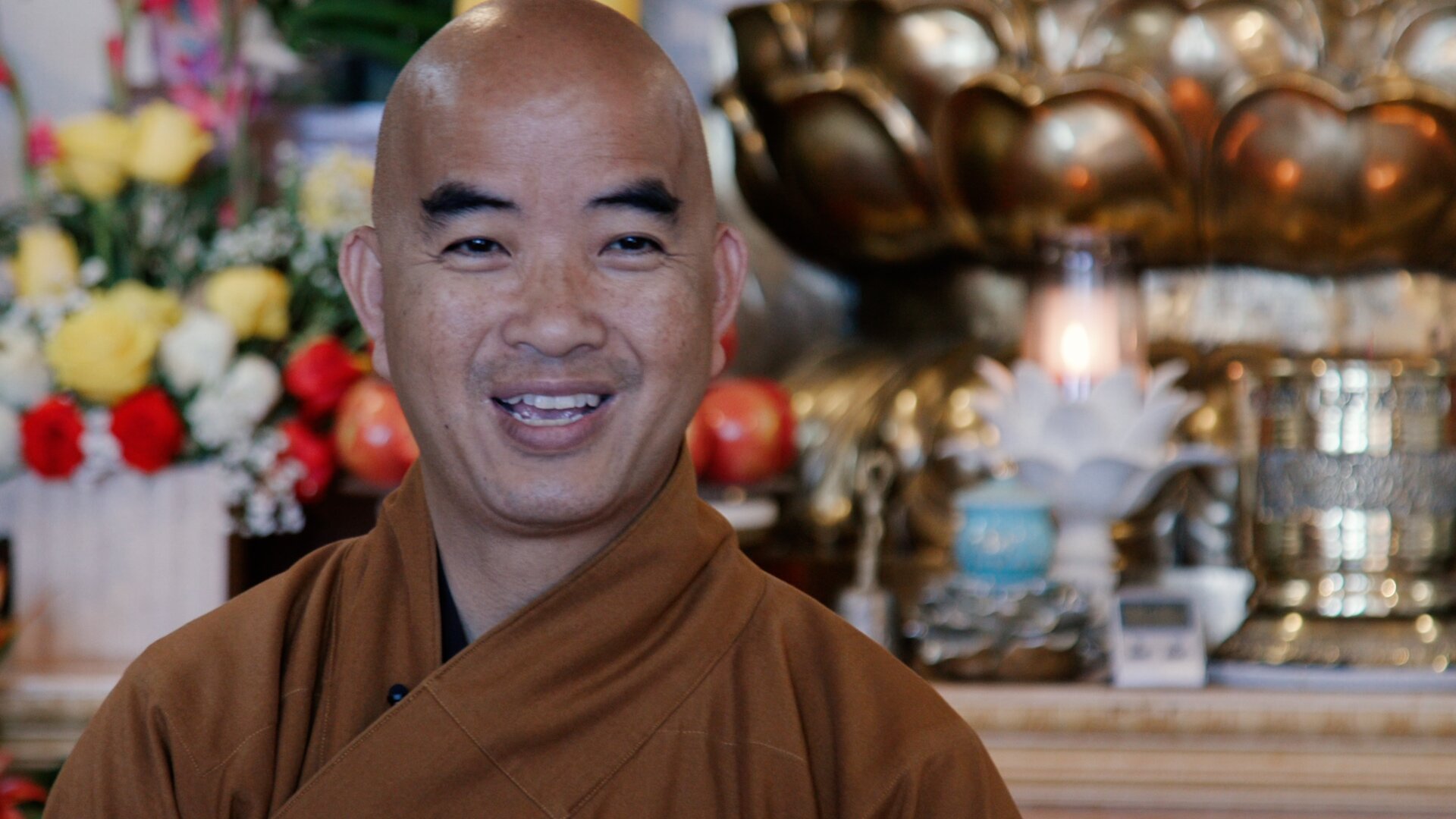

Reincarnation

“Death in my religion, Buddhist religion, is a time of continuation,” says Tinh Man, who is the Abbot, or leader, of the monastery. “When this body ends, we will continue to be reborn, what we call rebirth, to our next life.”

This concept of being reborn after death is known as reincarnation, and the form taken upon rebirth depends on the Karma cultivated during one's time on earth. Good Karma comes from positive actions.

“Do whatever is best to offer love and kindness, help people out, don’t harm people while you are alive,” says Tinh Man.

All living beings can be reborn and can return as any other living being - from a snake, to a dog, butterfly or mosquito. But having good Karma raises your chances as returning as a human.

“As a Buddhist, we would like to come back as a human, and continue as good humans with good hearts,” says Tinh Man. “To continue to serve the people, to do good things.”

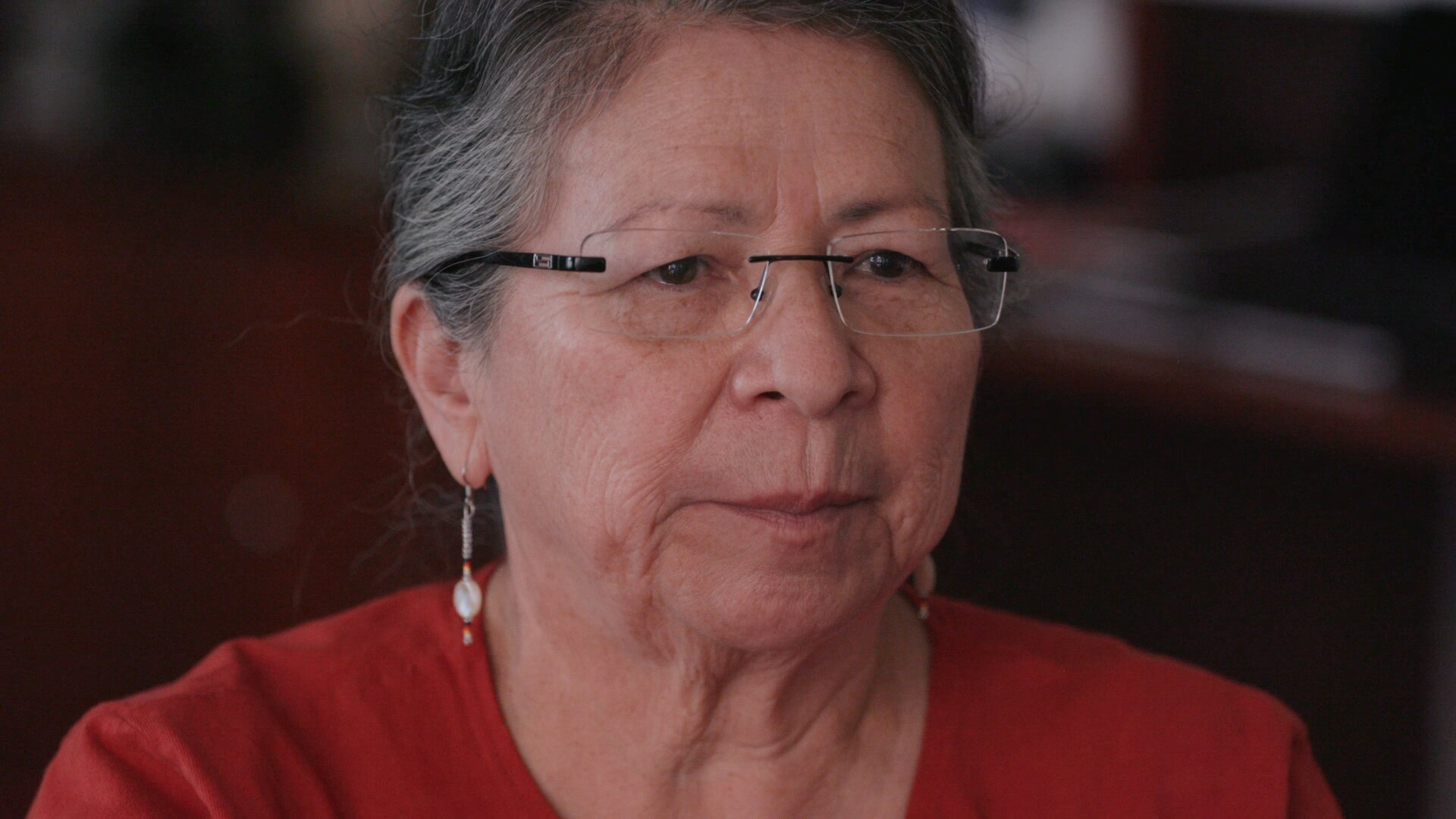

Día de los Muertos

“It is very important for us, particularly for our children, to get them to understand that death doesn’t mean it’s the end of something," says Castañeda. “It’s not the end of life, but it’s a beginning of another life, a spiritual life.”

Castañeda says the biggest misconception about the holiday is that it’s a "Mexican Halloween."

“It’s completely different. What we are trying to do is educate our children,” says Castañeda. “Some people will have a celebration just as an excuse to have another beer. It’s nothing like that. It’s a very spiritual and family-oriented celebration of life.”

Día de los Muertos — which translates to Day of the Dead — is a holiday that originated in Mexico and celebrates those who have passed away. It is traditionally celebrated on November 1st and 2nd.

“Death in my culture is a celebration of life,” says Castañeda, “it is that complete cycle of that sacred hoop.”

According to Mexican tradition, those who pass on join the spirit world. Altars, or ofrendas, are set up in homes to honor and remember lost loved ones. The ofrendas are adorned with photographs, flowers, candles, food, water and salt.

Lenape Nation

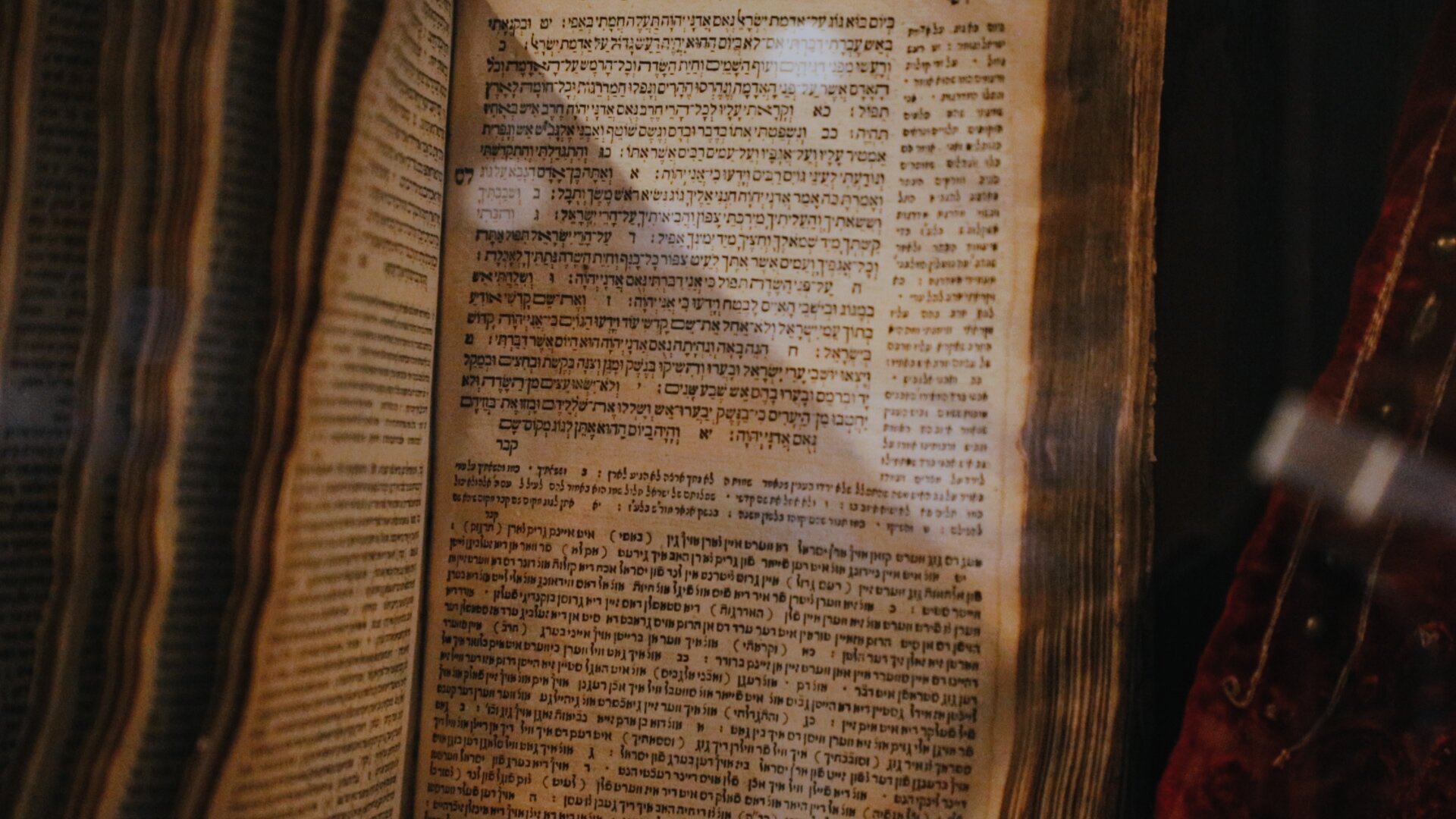

Judaism

Watch Colorado Voices: Dealing with Death

About 35 minutes from downtown Denver, up a long and winding road, the Compassionate Dharma Cloud Monastery sits on top of a hill overlooking trees and a small koi pond full of lilies. It’s known as the CDC Monastery and is home to several Vietnamese monks, who have come together to study the teachings of the Buddha.

As you walk down 45th Avenue near Grant Street in Denver’s Globeville neighborhood on Tuesday and Thursday evenings, you can start to feel the ground pulsing underneath your feet. Rhythmic drum beats rise from the basement of Birdseed Collective, a community center. Peek inside, and you’ll find Carlos Castañeda leading a GRUPO TLALOC Danza Azteca class.

The group performs traditional Mexican/Aztec dance, and will be part of a big Día de los Muertos celebration at La Raza Park in November.

When Curtis Zunigha is asked to explain a little bit about the beliefs held by the Lenape Nation, he looks me right in the eyes and says "No" with a straight face.

“No, I can’t tell you a little bit,” he says. “You’re asking for me to give you a lifetime of teaching.”

Patricia Noah, whose native name translates to "Chipmunk," pauses when asked the same question, but ultimately gives in.

“Christianity separates the spirit, creator or ‘God’ from the individual,” says Noah. “Whereas we see ourselves as all part of it.”

According to Lenape beliefs, everything has a spirit. Humans, animals, plants, rocks — even mountains and the Milky Way.

“The spirit endures beyond just the physical life,” says Zunigha, relenting to my question. “When your physical body is over with, you die in that way, but your spirit continues on, in a journey to the spirit world.”

In order to reach the spirit world, physical bodies must be buried instead of cremated. The deceased should not be autopsied or embalmed and death ceremonies must be performed. Without the proper rituals, spirits can get lost in a kind of purgatory, caught between the physical and spiritual worlds.

Lenape beliefs are also rich with metaphor.

“If you look at what we would call the cycle of life,” says Noah, “east is red, east is life and women. West is black, it represents men, and that’s where you go to the next world. The west.”

In a back corner office at Temple Emanuel in Denver, Senior Rabbi Joseph Black settles in. He’s wearing a suit, bow tie and yarmulke – a traditional Jewish cap – because he’s just come from presiding over a funeral. As a Rabbi, dealing with death is part of Black’s responsibility, and it’s a topic he’s spent a lot of time thinking and writing about.

“Death in my culture is seen as a part of life,” says Black. “It’s something that we need to be prepared for and that there are many rituals surrounding.”

Many religions have a clear vision of what they believe happens to our souls or spirits after we pass on. Jewish beliefs aren’t so succinct.

“There is a belief that there is a separation of our physical selves, our bodies which go into the ground, and our souls [which] return to God,” says Black. “After that, you can find reincarnation, you can find ideas of heaven and hell and purgatory. You can find almost anything in Jewish tradition.”

There are many rituals surrounding death in the Jewish religion, and they encompass everything from the timing of the service (traditionally as soon as possible, preferably within 24 hours) to the casket (plain, wooden and biodegradable) to the mourners, or immediate family, of the deceased.

“Once the body is buried then the focus shifts away from the deceased to the mourners and how we as a community can support them and honor the memory of their loved one,” says Black.

In the seven days following a funeral, known as shiva, mourners are expected to have no responsibilities other than dealing with their loss. The community brings them food, hosts services and comforts the mourners in any way they can.

After shiva there are rituals that continue for the first year after someone has passed away.

Black emphasizes that while "what happens after we die?" is a question in Judaism, it’s not the question.

“The Jewish question is ‘while we’re here, how do we make life most meaningful?’”