Climate report projects continued warming and declining streamflows for Colorado

Scientists predict with high confidence that Colorado’s future spring runoff will come earlier; soil moisture will be lower; heat waves, droughts and wildfires will be more frequent and intense; and a thirstier atmosphere will continue to rob rivers of their flows — changes that are all driven by higher temperatures caused by humans burning fossil fuels.

These findings are according to the third Climate Change in Colorado Assessment report, produced by scientists at the Colorado Climate Center at Colorado State University and released Monday. Commissioned by the Colorado Water Conservation Board, the report’s findings have implications for the state’s water managers. Borrowing a phrase from climate scientist Brad Udall, climate change is water change — which has become a common maxim for those water managers.

The report focuses on 2050 as a planning horizon and projects what conditions will be like at that time. According to the report, by 2050, the statewide annual temperatures are projected to warm by 2.5 to 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit compared with a late-20th-century baseline and 1 to 4 degrees compared with today. Colorado temperatures have already risen by 2.3 degrees since 1980. By 2050, the average year is likely to be as warm as the hottest years on record through 2022.

This warming, which scientists are very confident will come to pass, will drive the other water system changes that Colorado can expect to see. As temperatures rise and streamflows decline, water supply will decrease.

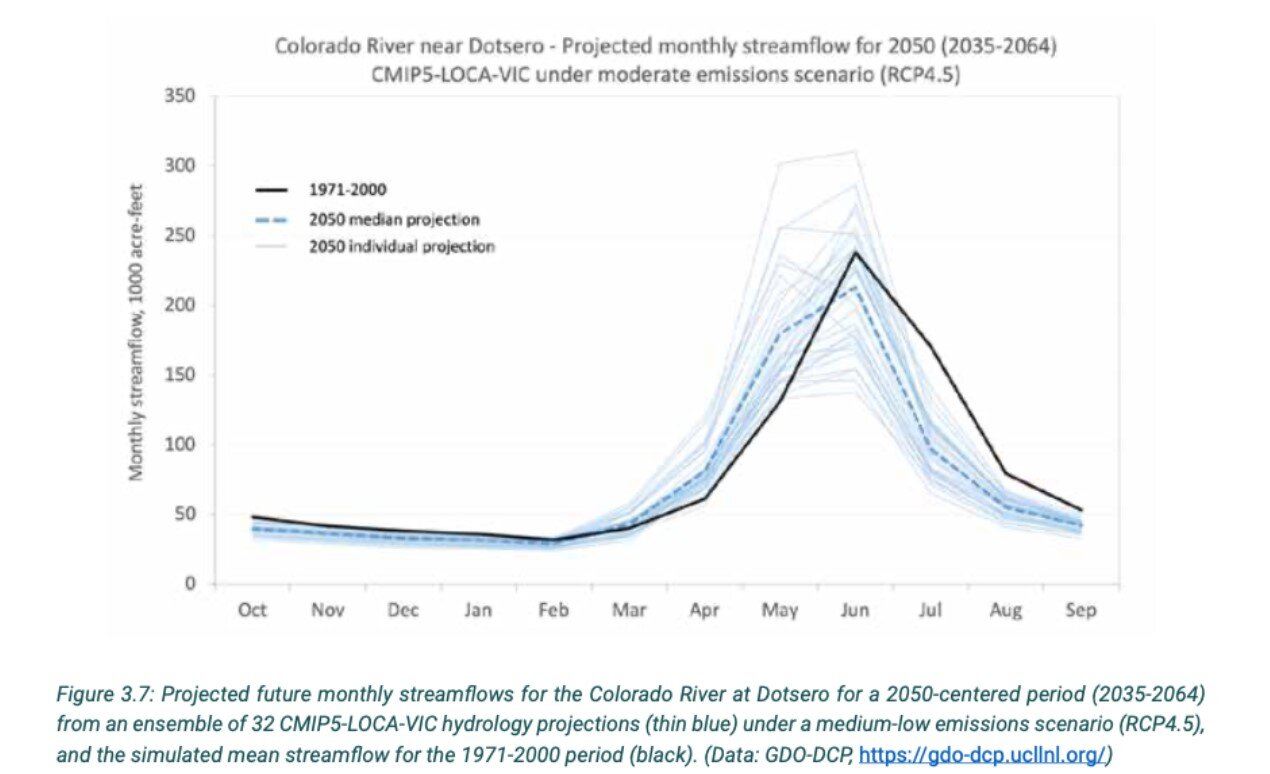

According to the report, by 2050 there will be an annual reduction of 5-30% in streamflow volume; a 5-30% reduction of April 1 snow-water equivalent (a measure of how much water is in the snowpack) and an 8-17% increase in evaporative demand (a measure of how “thirsty” the atmosphere is). A hotter, drier atmosphere can fuel dry soils and wildfire risk. Peak snowpack, which usually occurs in April, is also predicted to shift earlier by a few days to several weeks.

“Streamflows are primarily driven by snowpack that melts in the spring,” said Becky Bolinger, CSU research scientist, assistant state climatologist and lead author of the report. “When you are warming your temperatures, you are first changing the timing of when that snowpack will melt. And because we’re losing more to the atmosphere, that means we have less to run off in our rivers and be available for us later.”

Scientists are less certain about whether precipitation will increase or decrease in the future. Dry conditions have persisted across the state over the past two decades, with four of the five driest years occurring since 2000. Most climate models project an increase in winter precipitation, but they suggest the potential for large decreases in summer precipitation. But even if precipitation stays the same, streamflows will dwindle because of increased temperatures.

This graph shows the projected monthly streamflows for the Colorado River at Dotsero for 2050. A report on climate change in Colorado projects a 5-30% reduction in annual streamflow volume by 2050.

Credit: Colorado Climate Center

Planning for less water

CWCB officials hope water managers across the state will use the report to help plan for a future with less water. Many entities have already shifted to developing programs that support climate adaptation and resilience.

“I think we can say with confidence that it is more likely that we will have water shortages in the future,” said Emily Adid, CWCB senior climate adaptation specialist. “I think this report is evidence of that and can help local planners and people on the ground plan for those reductions in streamflow.”

Denver Water is one of those water providers that will use the report’s findings in its planning. The utility, which is the oldest and largest in the state, provides water to 1.5 million people and helped to fund the report. Denver Water has been preparing for a future with a less-reliable water supply through conservation and efficiency measures, reservoir expansion projects and wildfire mitigation.

“Projected future streamflows is a huge challenge for the water resources industry,” said Taylor Winchell, Denver Water’s senior planner and climate adaptation specialist. “The same amount of precipitation in the future means less steamflow because temperatures will continue to warm. … All this leads to this concept of uncertainty. We really need to plan for a variety of ways the future can happen essentially.”

Another finding of the report is that temperatures have warmed more in the fall than other seasons, with a 3.1 degrees Fahrenheit increase statewide since 1980, a trend that is expected to continue. Although it’s hard to pinpoint the exact cause of fall warming, Bolinger said it may have to do with the summer monsoons pattern, which can bring moisture with near-daily thunderstorms, but which have been weaker in recent years. That precipitation is critical, she said.

“First, you’re keeping the temperatures from getting too hot because you’re clouding over and getting storms,” Bolinger said. “And generally, with higher humidity, you’re going to have less evaporative loss from the soil. What we’ve been seeing in recent years is that we’re not getting that moisture in the late summer and into the fall.”

Less moisture and higher temperatures in the fall also leads to lower soil moisture and kicks off a vicious cycle of decreased water supplies. The dry soil gets locked in under the winter’s snowpack, and when spring melting begins, the water must first replenish the soils before feeding rivers and streams. This is what occurred in the upper Colorado River basin in 2021 when a near-normal snowpack translated to just 31% of normal runoff and the second-worst inflow ever into Lake Powell.

Some water-use sectors already experience shortages, especially those with junior water rights. Initiatives set up to support the environment and recreation are also at risk with shortages. And those shortages are likely to get worse in the future. In addition to grant programs, one of the ways CWCB aims to help these water users adapt is with a future avoided cost explorer (FACE) tool, which is outlined in the 2023 Water Plan. This modeling tool can help water managers figure out the costs of addressing — or failing to address — hazards such as wildfires, droughts and floods.

According to the report, extreme climate-driven events such as heat waves, droughts and wildfires are expected to be more frequent and intense.

“That gives you a little bit of perspective to say, ‘Well, what if I invest to mitigate this now, how can I lessen the potential impact in the future?,’” said Russ Sands, chief of CWCB’s water supply planning section. “I’m not trying to scare people; what we’re trying to do is motivate change and help them invest early.”

Despite the near-certainty of continued warming and resulting changes to the water system, Bolinger said there is a bright spot. Since the last time that a Climate Change in Colorado report was issued, in 2014, the world has begun to take action on reducing fossil fuel use and has shifted away from the worst-case scenario. Earlier projections were based on a “business as usual” assumption, with no climate mitigation.

“We do have things that have been put into place internationally like the Paris Accord,” Bolinger said. “We are more along the lines of a middle-case scenario. As long as we continue to take the actions that have been planned out, we are going to follow that middle scenario, which does show warming, but it’s not as bad.”