Author and naturalist Craig Childs eats crow over his younger self's mistakes

FRUITA, Colo. — Renowned author and naturalist Craig Childs doesn’t want you to read his most current book, "Stone Desert."

While speaking to a crowd at the newly opened Orbit Artspace in Fruita Childs said, “And one thing, if you do read it closely,” he interrupted his own thought and added, “which, don’t.” His non sequitur drew laughter from an audience who knew he wasn’t serious. And he wasn’t... mostly.

Childs welcomes you to read his book "The Secret Knowledge of Water," which explores the mercurial way water wanders through the desert southwest. You can read "Apocalyptic Planet" which observes the many apocalypses our planet has already survived and compares them to the human-imposed one we may be experiencing right now. But "Stone Desert?" Childs would prefer you didn’t dig too deep.

"Stone Desert" isn’t a new book. Childs' first work, it was initially published in 1995 by John Fielder of Colorado Photography fame. And when the book was published, the then-26-year-old Childs couldn’t have been more proud of his accomplishment. Now, it is the grown-up Childs who takes issue with the details his younger self missed.

A confluence of ideas

If you like books, and you’ve found yourself in Moab's cliffs, canyons and bookshelves, then you’ve likely explored Back of Beyond Books. Until just recently it was owned by Andy Nettell. Before he was a bookseller, Nettell was a ranger with the park service in both Canyonlands and Arches National Parks. This is when Nettell first read "Stone Desert."

With a winding trail of his own, Nettell went from being a ranger to buying a record store (selling CD’s) to selling books to publishing them. With "Stone Desert" long out of print, Nettell and a bottle of whiskey traveled from Moab to the San Juan Mountains with the hope of convincing Childs to do a re-print of the original. This wasn’t the first time they would have this conversation. But it was the last, as Childs finally agreed to it.

The truth is in the Journal

Childs was a river guide in the early 1990s. Guiding was a seasonal job that left the winter months available for more work, or exploration.

Childs said, “The best thing that I could do was disappear into the wilderness for that period of time. [It was the] cheapest thing you can do. No spending any money … you spend all the guiding season gathering granola bars at the end of every trip. And so I had like 200 granola bars just to see me through the whole winter.”

In the fall of 1993, Childs planned to explore the backcountry of the canyonlands on foot for most of the winter.

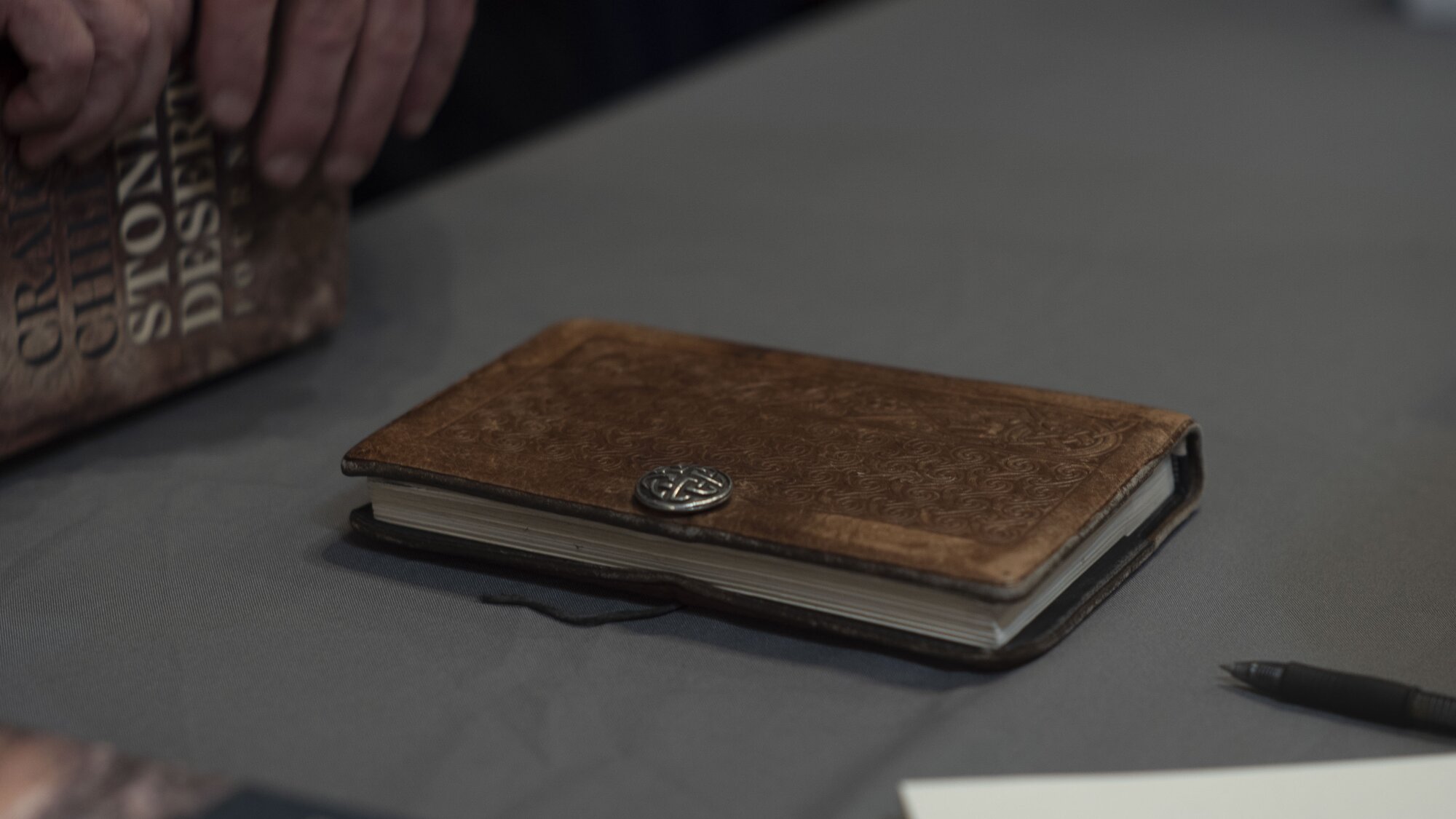

At that time Childs was a writer, but nobody knew it. He was very intentional in recording his experience and observations that winter. He had purchased an expensive leather-bound journal to take with him. Now, the veteran author uses whatever bits of paper he can fit in his back pocket for note-taking. But, at a time when he had to convince himself, he was a writer (with no published book to prove it) he needed a symbol to help him. That symbol came in the form of the journal.

“Back then I was saying, ‘Okay, if you're going to write, take your pack off, unzip, pull this out, sit down and focus your attention,’" Childs said. He wrote all that winter. He continued, “I wrote and drew sketches of what I was seeing, potsherds, birds and ravens, and whatnot.”

The 26-year-old made a record of what a 26-year-old saw.

“I didn't know what I was talking about. I was just out wandering, looking at things, studying … I was carrying scientific journal articles with me," Childs said. "I was carrying naturalist guides with me. I was trying to learn this place."

The 26-year-old saw ravens and sketched them and wrote “crow” under them. A naturalist should know the difference between a raven and a crow. Nonetheless, the young naturalist had a strong voice forming and a passion to communicate. His inaccuracies didn’t turn off John Fielder and the original Stone Desert was published.

The two become one

When Nettell came to visit, Childs recalled him asking if he still had the old journal. Childs said he did and presented it to Nettell.

“He looked at it and he said, ‘You know, we have to do the journal as well as the book,’” Childs said. And that’s what ultimately happened: two books in one book. One-half of the book is a reprint of the original Stone Desert. Flip the book over and it’s a facsimile of Childs’ journal, with no corrections. And that’s what gives Childs pause in encouraging people to read it.

“Because it's personal. I mean, who wants to see their journal from when they were 20-something years old be seen by anybody, at all?” asked Childs.

But that's what Childs chose to do: to share a record of an author who was still growing into himself.

Childs can be referred to as the Edward Abbey of our time (minus the misogyny). That is a tall order but it is well-deserved. Letting his journal be published in the raw was an act of humility. Childs is sharing with the rest of us the truth of all the greats: they weren’t always great. That being said, the voice we hear when reading any of Childs books comes ringing through in "Stone Desert."

And Childs' real voice, the one that comes from his mouth, silenced a crowded room in Fruita as he shared the story of seeing Dead Horse Point in the moonlight in those early days before he was Craig Childs the author.

“I walked out and sat at the edge of Dead Horse Point looking down into Canyonlands in the moonlight. And it looked alive. It looked like it was growing and thriving and moving. And you could see the blue shadows dropping into canyons and you could see all the towers,” he said. Then he recalled saying to himself, “Whatever it is you do in your life, this is in the middle of it. Never leave this place.”

He added, “And my heart has always been there.”

Many people see a division between their own humanity and nature; they need a guide to pull them through the vale and see the division isn’t real. For almost 30 years Craig Childs has been taking people, one written page at a time by the hand, and sharing what his younger self saw. A line of beaming faces waiting for his signature is a testament to this.

Cullen Purser is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at cullenpurser@rmpbs.org.