Community-led air monitoring in Commerce City reveals gaps in environmental regulation

COMMERCE CITY, Colo. — In June of 2023, results from a community-led air monitoring project in Commerce City affirmed decades-long claims of health ailments due to pollution.

Cultivando, the organization that led the efforts, hopes the new data will help create policies that enforce better environmental regulations in the area, and empower residents to more effectively advocate for their health.

“I think that once state governments, policy makers, those with power to influence change have the data in front of them, and the data is telling them very sobering and very urgent findings, it is up to them to act on it,” said Laura Martinez, manager of environmental justice at Cultivando.

Located in one of the most polluted zip codes in the country, Commerce City residents are surrounded by various factories and major highways, which are tied to a lack of vegetation, noise pollution, and higher temperatures.

Homes in Commerce City that sit alongside I-70, between various manufacturing facilities.

Photo: Elle Naef, Rocky Mountain PBS

The air monitoring system led by Cultivando came with two main takeaways. By monitoring more toxic substances than the current EPA regulations require, Cultivando found other toxic elements being overlooked. These toxic elements included methane (not previously monitored in “ambient” areas surrounding facilities), radioactivity and hydrogen sulfide. And by monitoring in 10 to 15 minute intervals instead of the state’s hourly intervals, they found peaks in air pollutants that had not previously been documented.

In 2019, a Suncor facility malfunction caused a shower of clay-like residue to cover the surrounding neighborhood. Suncor offered free car wash certificates to neighboring residents impacted by the incident.

In 2020, Suncor lost a $9 million settlement after state regulators sued the refinery for air quality violations.

The court mandated that $2.6 million of the settlement go toward grants for community-led environmental projects. Cultivando was awarded $1.8 million for an air monitoring project independent from those carried out by Suncor and the State of Colorado.

The organization contracted Boulder AIR, an independent air monitoring company, to equip the project and help evaluate the data collected.

In order to gather air samples not yet collected by other entities, selected residents of the area were given at-home monitoring devices. They logged symptoms such as headaches, nosebleeds and other health issues in order to note possible correlations between spikes in pollutants and daily health impacts.

Boulder AIR then deployed stationary units and luminal canisters that collect air samples when pollutants are detected, throughout the neighborhood surrounding Suncor.

Pollutants were also tracked in 10-15 minute increments instead of hourly increments as regulated by the EPA.

This included Particulate Matter 2.5, or PM 2.5, which can cause many of the ear, nose and throat symptoms residents claimed to be experiencing, in addition to the risk of long term effects on the heart and lungs.

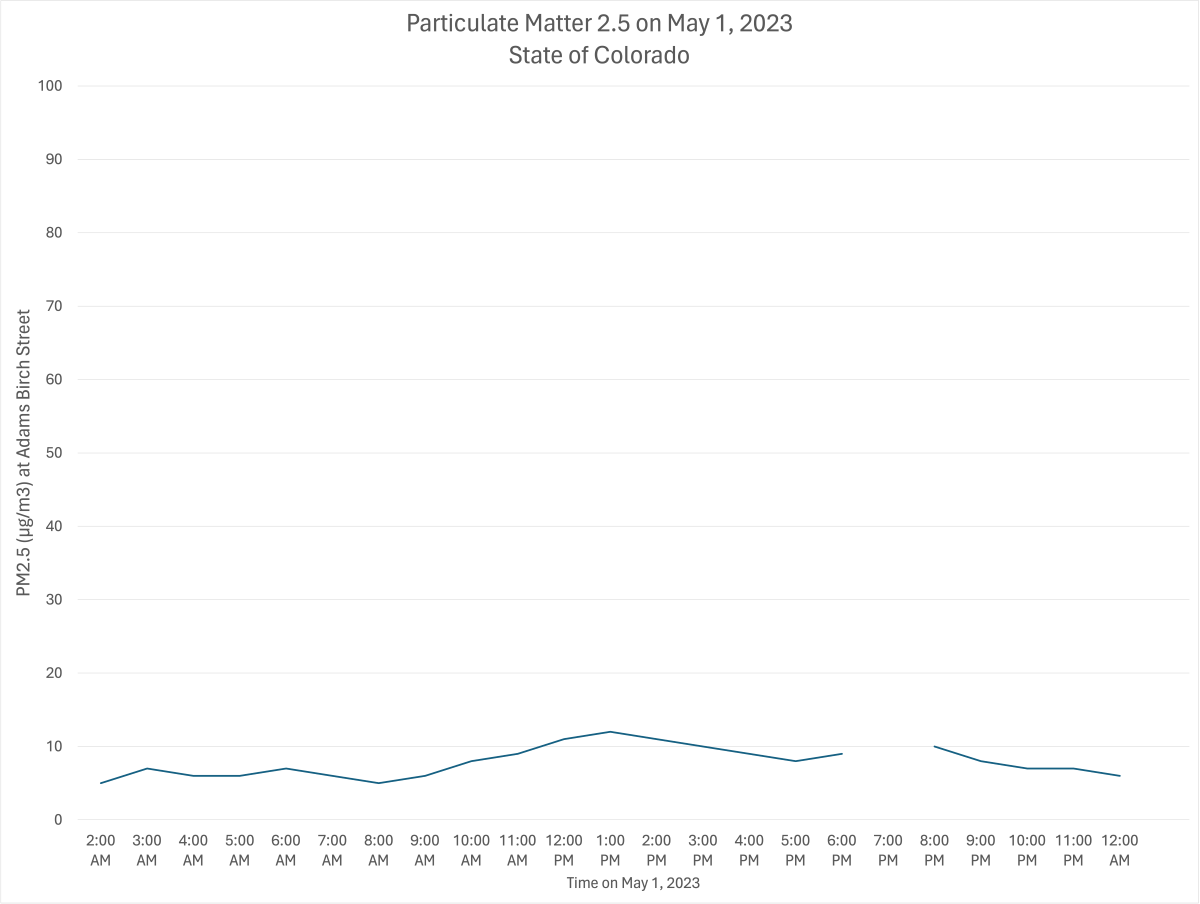

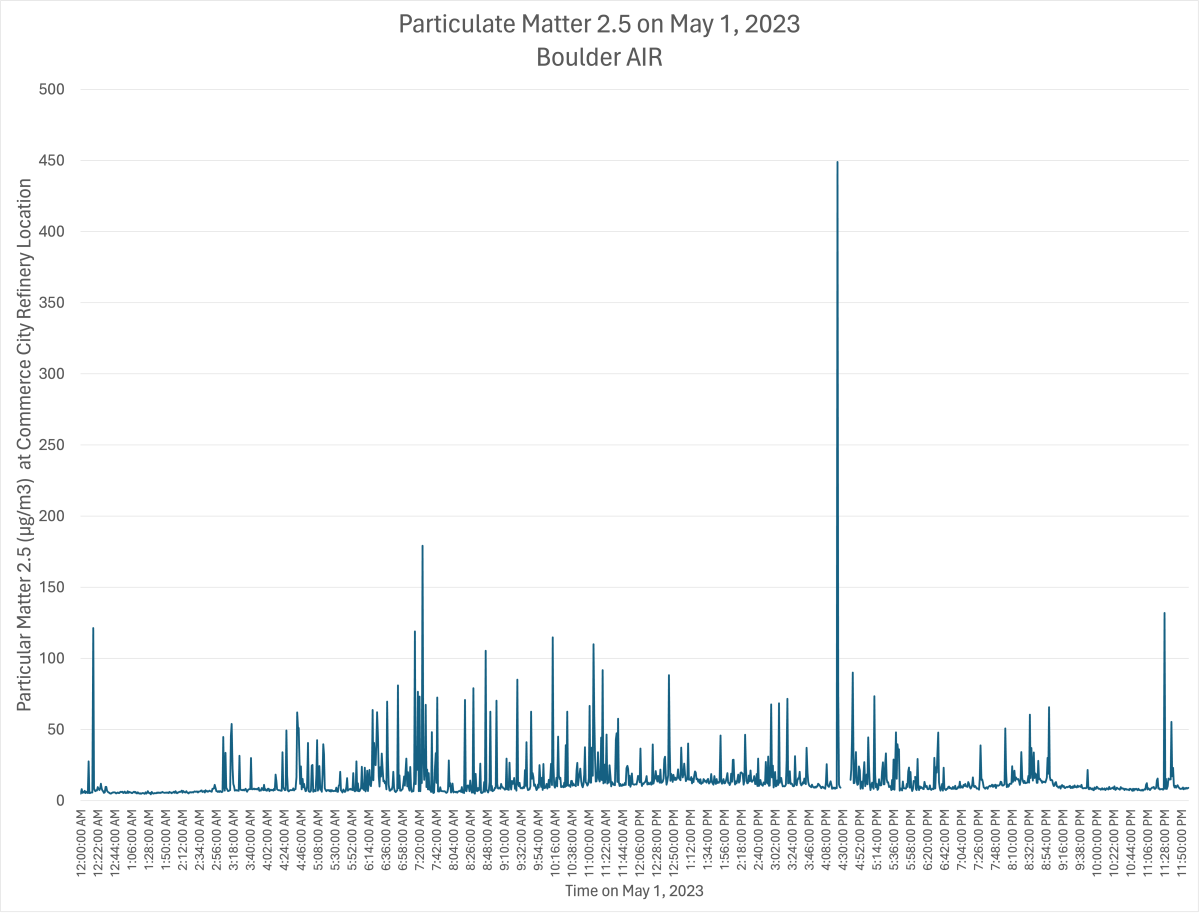

By monitoring in shorter time increments, Cultivando and Boulder AIR found significant spikes in pollutants like pm 2.5 that hourly measurements failed to document.

“The state takes averages, but our community doesn't breathe in averages,” said Martinez.

Measurements taken by Boulder AIR show more significant peaks in Particulate Matter 2.5 than state measurements taken in hourly increments.

Throughout the air monitoring process, Cultivando launched community education efforts.

As data was being collected, the organization presented findings in neighborhood meetings, educating residents on the health impacts of the air pollution, and affordable ways to minimize risk such as homemade air filters.

They also created an intern program for high schoolers — one Martinez said “provided a path for them to continue to advocate for themselves and their family.”

Dr. Priyanka DeSouza, Assistant Professor of the Urban and Regional Planning at CU Denver will be using the community-led air monitoring data to advise the state on new models of air monitoring that would account for pollution “hotspots.”

She said that as of now, efforts at CU Denver are focused on harmonizing data collected by Cultivando with that of the state.

“Our long term goal is to develop an air pollution database for Denver to identify hot spots more broadly across the city, and identify ways to streamline future air pollution efforts so nobody is replicating the work organizations like Cultivando have already done.”

In order to help bridge the gap between community members and policymakers, DeSouza said she hopes Cultivando will also work with CU Denver on a communication strategy.

“We want to use this data to create space for the community and regulators to come together to discuss potential policies or solutions forward,” she said.

Martinez said that the current methods for identifying health issues can also leave areas such as Commerce City overlooked.

Currently, data collection on things like cancer rates are aggregated at a county level instead of by neighborhood. In doing so, the data does not account for the fact that more rural areas in Adams County do not have the same health impacts as areas like Commerce City, therefore it does not properly demonstrate the relationship between air pollution and disease rates.

Martinez said that in addition to helping optimize air monitoring processes, Cultivando hopes the gaps found in the states data collection processes will help with DeSouza in her efforts to create a health impact tracking system that would evaluate the health impacts by neighborhood, a system known as “census-level” tracking.

“We hypothesize that the rates are going to be significantly higher [in Commerce City] because of the contamination in their air, their water and their soil,” said Martinez.

According to Michael Ogletree, director of the air pollution control division for the State of Colorado, efforts to improve the accuracy of air monitoring have been put into place since 2021 upon the passing of the Regulate Air Toxics Act.

The act requires the state to determine five priority air toxics to present to the Air Quality Control commission for regulation.

Ogletree said data already collected by independent efforts such as Cultivando’s contribute to an ever-improving monitoring system.

“Having that additional data helps us to inform policy that we could then take to the air quality control commission to be able to pass additional regulations,” he said.

Guadalupe Solís, director of environmental justice at Cultivando, said that beyond the data, the multiple settlements and a need for community-led initiatives illustrate a legacy of environmental racism.

She cited that levels of any given pollutants were “astronomically higher” in Commerce City, which is demographically made up of immigrants, non-English speakers and other Black and Brown working-class residents, compared to nearby cities such as Boulder and Broomfield which are majority white, traditionally educated communities.

“I think if a refinery were to be built somewhere like Boulder or Broomfield, that wouldn't be allowed to happen,” she said.

Elle Naef is a multimedia producer for Rocky Mountain PBS. ellenaef@rmpbs.org