Gene bank in Fort Collins stores millions of plant and animal samples

FORT COLLINS, Colo. — The National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation may not look like much from the outside. But the unassuming building surrounded by Colorado State University’s campus in Fort Collins is home to a massive gene bank where hundreds of samples of genetic materials essential to agriculture are stored.

“Our collection is by far the largest, most diverse collection that you're going to see when you start looking at other national gene banks,” said Harvey Blackburn, the national coordinator of the National Animal Germplasm Program.

According to Blackburn, his program’s collection has over 1.1 million samples, representing over 150 breeds of livestock.

Gayle Volk, a research plant physiologist, is one of the scientists working on the plant side.

“Our national gene bank has about 600,000 different accessions of different kinds of plant materials,” she said. “This represents around 2,500 different plant general and about 16,000 different plant species.”

Why store millions of samples? For present and future generations.

“The materials we have are distributed to scientists and researchers throughout the world, and those are used in breeding and research programs so that we can improve agriculture everywhere and feed the planet successfully,” explained Volk.

With so many diverse materials, the gene bank can be used for a variety of reasons.

A disease could emerge that wipes out a large population of livestock. The genetic diversity lost could be replaced because the gene bank has it safely stored away.

Or a plant breeder could introduce new sources of resistance to such a disease by acquiring plant materials from the bank. Volk pointed out that this is already happening in New York where researchers have provided genetic materials from a crop wild relative species of apple that “have new strains of resistance to diseases such as apple scab.”

This could also be done for drought or heat resistance, for example, which is especially important in the face of climate change.

Blackburn explained: “We've collected samples from all over the United States, whether that's going to be in temperate areas like here in Colorado or a lot further south say along the Gulf coast region of the United States where animals may be better adapted to a higher degree to various factors such as heat, temperature, [or] stress that they may encounter.”

According to Blackburn, this idea could even go so far as to reduce methane emissions from the livestock sector by introducing select genetic material.

For plant materials, the Fort Collins facility also acts as a backup for other gene banks in the national system. For livestock, this is the only facility of its kind in the nation.

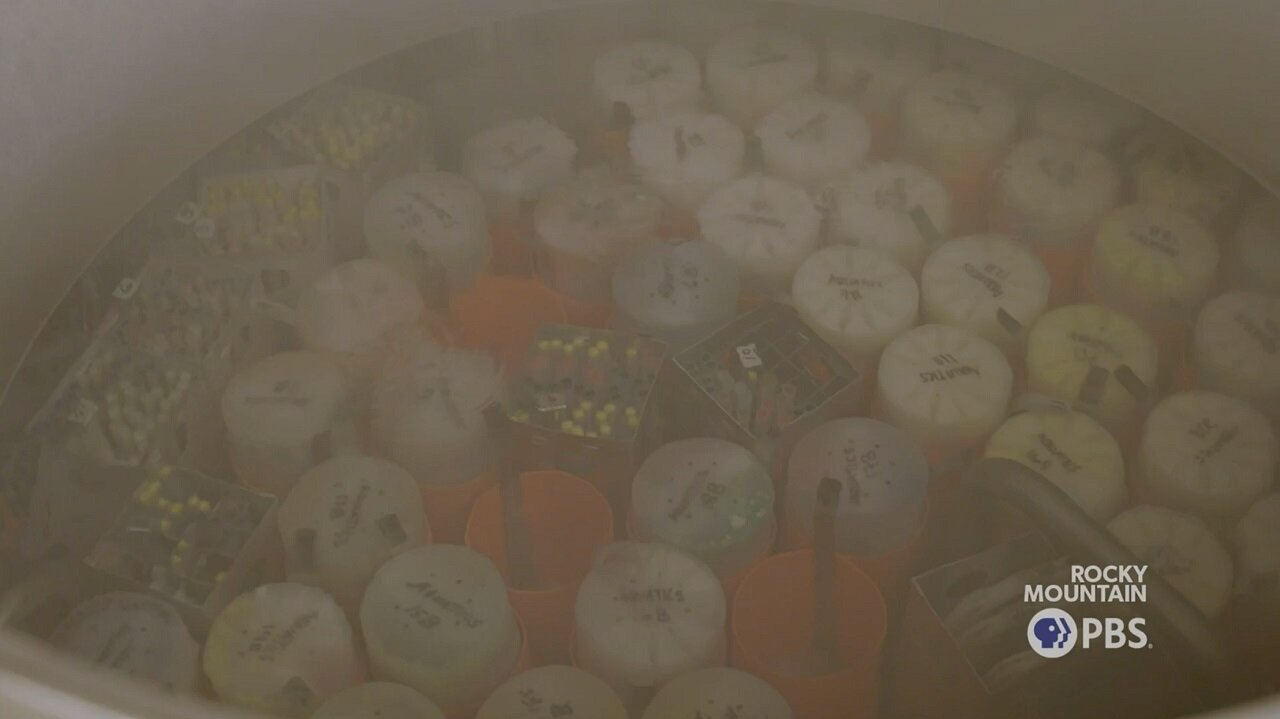

This means a lot of freezing.

The freezing process for a given sample depends on the type of sample. Scientists must worry about moisture, proper protectants, and how samples will be stored. Samples can be stored in a freezer at -18 degrees Celsius or into tanks where they either sit in or above liquid nitrogen.

Related Stories

But not all materials have been frozen. Volk explained that there is a lot of “non-seed crops that either we haven't had the technologies available to us or the methods to successfully cryopreserve and store them here, or we haven't finished processing all those materials yet.”

This technology hurdle is something that the laboratory is also working on. Prior to ten years ago, there was no method to cryopreserve citrus. Now, researchers can place millimeter sized shoot tips into liquid nitrogen.

“We then pull them out again and grow the full plants and within a year we have a flowering tree,” Volk explained. “We’ve [used] this method now for over 400 different kinds of citrus that we have in our national gene bank.”

For animal collections, Blackburn has started looking at collecting ear notches to “essentially clone” animals even after freezing.

“The ease with which we can do that today did not exist 20 years ago,” said Blackburn. “Over time, there's going to be new developments that will enable us to collect tissues much easier and allow us to freeze better.”

This is becoming more and more important as agricultural pressures increase—especially climate change.

“If we think about it in 150 years, we have no idea what kind of problems people are going to be facing,” he said. But preserving as much genetic diversity as possible will protect and prepare future generations.

Clarissa Guy is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at clarissaguy@rmpbs.org.