Colorado scientists uncover oldest female infant burial in Europe

DENVER — A team of archaeologists in northwestern Italy has found what is currently the oldest female infant burial in Europe, dated to about 10,000 years ago.

Two Colorado scientists, Dr. Jamie Hodgkins and Dr. Caley Orr, headed the research team and co-authored the publication. To read their published article in Nature, click here.

Orr is a paleoanthropologist and an Associate Professor at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. Hodgkins is a paleoarcheologist and Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Colorado Denver.

The two were initially interested in the specific site—the Arma Veirana Cave—for its Neanderthal potential.

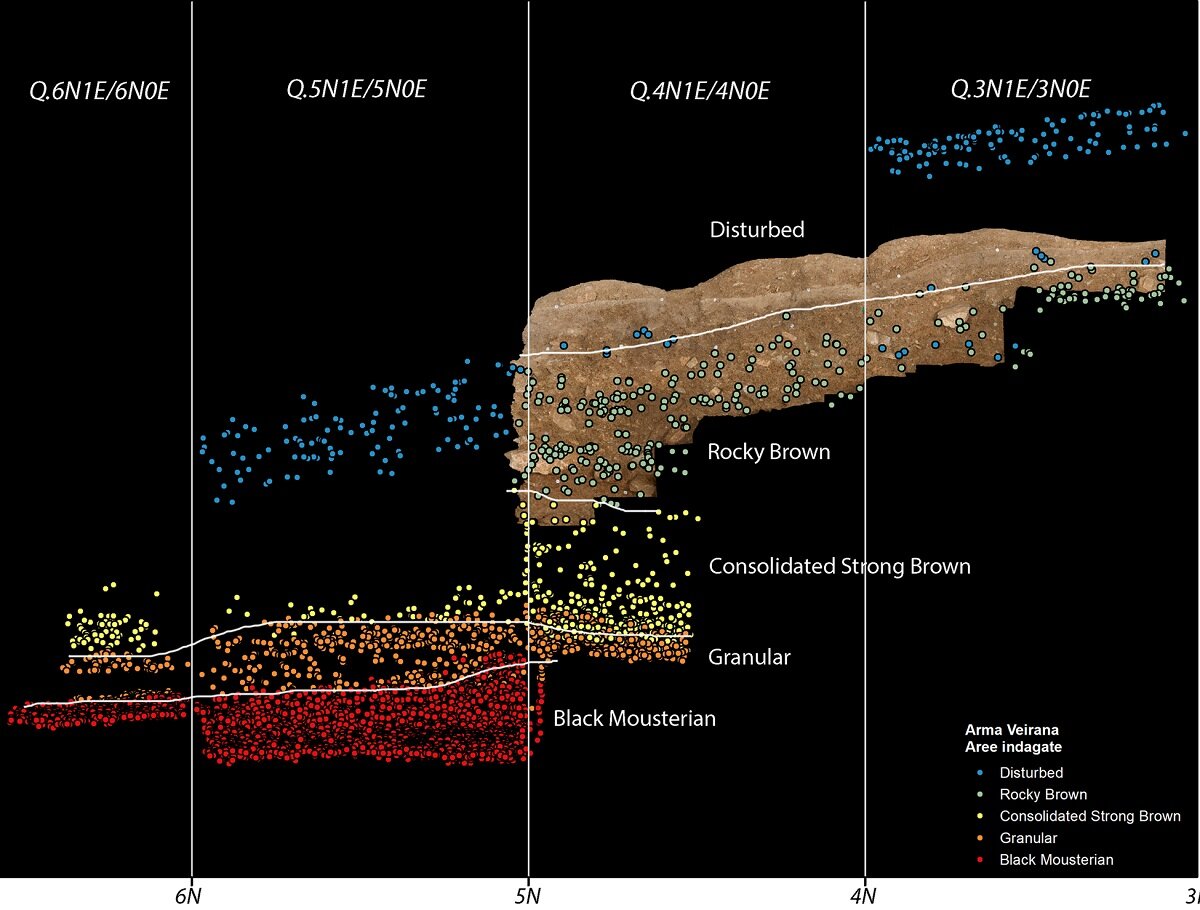

“We started working at the site…in 2015…looking at these Neanderthal levels, which have produced a really rich record of what we call Mousterian tools,” said Orr.

Mousterian tools are typically stone tools associated with Neanderthals and early modern humans. These are found in the Middle Paleolithic Era, also known appropriately as the middle of the Stone Age.

Some of these tools, however, didn’t particularly fit well into a specific time period.

“So, we knew we had people using this cave over the period of time we were interested in looking at and we knew we probably had both Neanderthals and modern at some point,” said Hodgkins.

“And so, it was very strategic in terms of how we excavated,” said Orr. “And we came down on a little bit younger sediments than we were expecting, but we came across a thin Mesolithic layer.”

It was upon moving deeper into the cave into younger sediments that the team made their burial discovery.

“We ended up kind of bit-by-bit finding evidence of this material culture,” recalled Hodgkins. “We were finding pure shell beads that were coming out in increasing frequencies.”

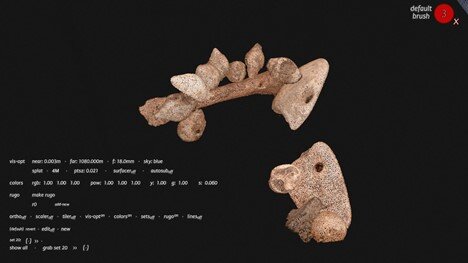

In this first season, the team also uncovered a fragment of the cranial vault—a part of the skull, hand bones, and tooth buds. Tooth buds are very young teeth that have not yet developed roots.

“And so, we knew we had a very, very young infant,” said Hodgkins. She remembered sitting in the lab, filtering sediment bags with one-millimeter screens to catch the tiny bones.

But the team ran out of time that season. So, they covered the site as best they could and hoped it wouldn’t be disturbed until they could return the next year.

“And we lucked out,” Hodgkins said. “And so, we were able to then excavate the rest.”

The team was able to determine that the child was about 40 to 50 days old, female, and buried 10,000 years ago during the Mesolithic Period. This makes it the oldest female infant burial in Europe.

There are other burial sites across Europe that are older. However, young individuals are especially rare for a few reasons.

First, their bones are cartilage as they aren’t fully ossified…and they are very small. This leaves little for archaeologists to find thousands of years later.

Further, when infant mortality is high, burials are less common. “You don't necessarily attribute personhood to them or include them necessarily within your group until they reach a certain age at which you're fairly sure that they will survive,” explained Hodgkins.

According to Orr, the child is also significant because “it provides a data point for a time period that's not very well known, especially in Southern Europe where there are very few early Mesolithic sites.”

And data during this time period are valuable in understanding how early humans transitioned from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a more sedentary and agricultural way of life after the end of the Ice Age.

“[It’s] a really interesting time because…you're at the beginning of the Holocene when temperatures are warming and right at about 10,000 years ago is when we start to see the invention of domestication in many different parts of the world,” explained Hodgkins. “And what that ushers in is this whole reorganization of how humans live on the landscape, particularly within Europe.”

The team gave the child (scientifically known as AVH-1) the name Neve, which means snow in Italian.

The name, explained Orr, came from his misspelling on a sample bag of the Neva River Valley in which the cave rests. But an Italian collaborator explained the meaning of the word and “became a little wistful over it,” so it stuck.

But Orr recognizes that naming archaeological finds such as this is controversial.

“She's from a cultural and a time period that is far removed from us,” he explained. “Certainly, her people probably gave her a name and we are imposing it to some degree on her.”

He feels that critics have a very valid concern. He also feels that giving the child a name is both more humanizing and shows the emotional attachment the team has developed over two seasons.

“I think most of the team really, we felt some emotional attachment to this child and could certainly relate, many of us being parents, to the loss of that child,” Orr said.

“What we're trying to do is investigate human history and basically the humanity of the past,” said Hodgkins. “We're talking about mothers and fathers in the past, we're talking about aunts and uncles, we're talking about cousins, entire groups that are caring for individuals and all having a different relationship to each other and a different relationship to being human.”

Orr said that the team could call the child Neve or AVH-1 and for them, it was more “humanizing to give her a name.”

This emotional attachment was especially poignant for Orr and Hodgkins, who are not only co-workers, but husband and wife.

The summer they discovered the burial site was when Hodgkins found out she was pregnant with a girl. And only six months before, she had had a miscarriage.

“So, to understand loss so immediately I think really added to our connection to this particular individual,” said Hodgkins. “And certainly, it gives us a deeper lens in which to understand the significance of what it's like to lose a child, to bury a child, to find a child.”

Hodgkins and Orr see this connection through time with Neve in how she was buried. At only two months old, the infant was buried with over 60 pure shell beads and four pendants. There was also evidence that many of the items were worn previously and were passed down like family heirlooms.

“It’s clear that they were giving her personhood, they were giving her significance. They were saying you are one of us and we're returning you to the earth…I think that's something that is really special for this little girl.”

Clarissa Guy is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at clarissaguy@rmpbs.org.

Here is where you can watch a flythrough of the Arma Veirana cave where this discovery was made.