Justice fund provides a lifeboat for immigrants in a sea of challenges to win asylum

DENVER — “I thought of coming to the U.S. because I've always believed that the U.S. is one of those countries that can hear your story. The U.S. is one of those countries that I thought could fight for you, ” Selky Azaah said when thinking about his plight to escape almost certain death in his home country and creating a new home in Denver, Colorado.

As a former pastor, Azaah doesn't like to consider himself lucky; he likes to call himself blessed. Blessed that he was able to survive a brutal civil war, a rigorous journey to the United States, and win asylum after being in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody at the Aurora GEO Detention Center for eight months.

Azaah is from the English-speaking part of Cameroon, an African country that has been in the midst of a civil war for the last five years, though the conflict had been building for decades. France and Britain colonized the country during the first world war. In the 1960s, when many African countries were gaining independence, the United Nations gave the British parts of the country the option to either join Nigeria or the French part of Cameroon. Some parts chose to join Nigeria, while others opted to join what was Cameroon. Since then, the French-Cameroon government has tried to eliminate British culture and the English language.

“They were trying to turn English Cameroonians to French Cameroonians,” Azaah explained. “They're trying to eliminate the English language and our English culture to make Cameroon have one language, which is just French.”

Gradually, the French Cameroon government tried to eliminate the English school system and started appointing only French magistrates to rule over the English parts of the country. In fall of 2016, protests by the English-speaking Cameroonians filled the streets. The French government responded with violence.

“And during those days it was so horrible and people were being arrested illegally and people were being killed ... I've lost a lot of cousins, a lot of friends. And, you know, they were just killing indiscriminately," Azaah said as he recounted the conditions he was living in at the time.

One day, the French Cameroon police knocked on his door and found t-shirts Azaah had printed that they didn’t approve of. Azaah told Rocky Mountain PBS the police beat him and took him to a military camp that had a reputation as a place where people went and never came back. Afraid for his life, he bribed an officer to let him go.

“So the guy took the money and then he was like, ‘You can run away from [here].’ So, when I started running, I didn't know … I had a second thought in my head that this guy could attempt to … kill me and probably say I tried to run away,” Azaah said. “So, when I jumped into the closest bush, I just laid on the ground, immediately laid on the ground. He started shooting … and he knew I was dead. He knew he shot at me. I was dead. So, I had to creep on the ground like a soldier.”

After crawling away, Azaah ran back to his house. He then took his wife and two kids to his mother’s village.

When they discovered he was not dead, the police came looking for him, so he decided to flee the country, leaving his family behind.

“So I told my wife, ‘Oh, you just have to be strong,’” said Azaah.

Azaah traveled to Nigeria first, but feared he would be sent back to Cameroon. After hearing he could travel to Ecuador with his passport, he decided to go to South America and make his way north to the United States. Struggling through dangerous conditions, he arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border and was sent to the Aurora GEO Center in January 2019.

Inside the detention center, a wave of depression hit him after learning some tough news.

“My cousin was shot dead because of me. I lost my grandma and my other cousin. So I became kind of depressed and … my world was crumbling,” Azaah described about his mental state at the time.

On some advice from others to help him with depression, he started accepting visitors and met several members and friends of the Denver Community Church who came to visit.

“It came to our attention that there's just a deep level of loneliness for folks who are in detention. And so a simple way we can show up for them is to exercise their rights to visit them,” said Dave Neuhausel, a pastor at Denver Community Church.

Greg Mortimer said Denver Community Church's focus on issues of justice and peacemaking in the city led him and his wife to the congregation.

“We originally started coming here [Denver Community Church] because at that time in 2018, my friends and I were trying to bring alongside as many people as possible to … help us with these visits into the Aurora GEO detention center,” said Mortimer.

During his visits in 2019, Mortimer met Azaah, heard his story, and made an immediate connection.

“[Among] those that were visiting … was a wonderful man that I know called Greg, who is like a friend, an uncle, and a father to me right now,” said Azaah. “We always go back and forth and say, ‘No, you are the best. You're the one that impacted my life.’ And he keeps saying, ‘You're the one.’”

Mortimer and his friends who got to know Azaah soon realized that in order for him to live, he needed to win his asylum case.

“And if he lost his case, that meant that he would be deported. And we thought that was quite likely a death sentence,” said Mortimer.

The group found an immigration lawyer and paid him the $6,000 needed right away and set up an online fundraiser for reimbursement, which only took a week to meet its goal. So in July 2019, Azaah was able to go to court with an attorney by his side.

“Just imagine you are in the middle of the sea and you're drowning. You have no hope and you cry, and then suddenly a boat shows up. How are you going to feel?” said Azaah. “It really boosted my spirits.”

In immigration court, there are no public defenders provided by the government. The Sixth Amendment, which guarantees people the right to an attorney and will be provided one if they can't afford or find one, doesn't apply there because deportation is classified as a civil, not criminal, sanction.

A 2015 study from the University of Pennsylvania Law Review found represented detainees were ten and a half times more likely than those who represented themselves to be released from a detention center. With similar data of their own, Mortimer and his friends realized raising this money for legal counsel could save more lives.

“That was kind of the beginning of us thinking, you know... if in that amount of time we could raise that much money, what if we could start to kind of operationalize this and take it to the next level?” explained Mortimer.

So over the last two years Mortimer helped create the Colorado Immigrant Justice Fund (CIJF). In 2019, they operated with ad hoc fundraising campaigns but were able to help 15 immigrants win asylum. In 2020, they were able to raise about $60,000 helping nine immigrants win asylum. Now they have nearly 130 monthly donors giving a total of about $4,800 per month.

“Hearing the stories of—honestly—suffering, being betrayed, losing almost everything, and literally losing family members at times...to feel their pain, to hear their pain, and hear these incredible, miraculous stories about how they're even alive was so humbling for me,” said Newhausel.

He was one of those who consistently visited people in the detention center before the pandemic. When Mortimer approached him with the idea of the CIFJ, he knew the organizational arm of Denver Community Church, Project Renew, could help.

“One of the values of Project Renew is radical generosity. And so, what we've done is because of the generosity of several other donors, we've made it easy to set up these targeted funds for specific areas of focus. And so one of those is the Colorado Immigrant Justice Fund,” explained Newhausel. “So for folks who want to donate to the Colorado Immigrant Justice Fund, every dollar they give will go 100 percent toward the services that are being provided for these very vulnerable immigrants who need legal representation.”

The pandemic has made CIJF’s work more difficult, with ICE closing down visitations for most of the last year and a half. Volunteers were not able to have those crucial visits to find people who could use the help of an immigration lawyer. But just like the rest of the world, CIJF adapted and created a pen pal program reaching those in detention all around the country.

“That program has grown to the point where we've had over 500 new volunteers who have corresponded with close to 900 immigrants in 39 detention centers around the country,” Mortimer said. “Those are the folks in relationship with people in detention and who understand on a very human to human level the need for that. [legal representation]”

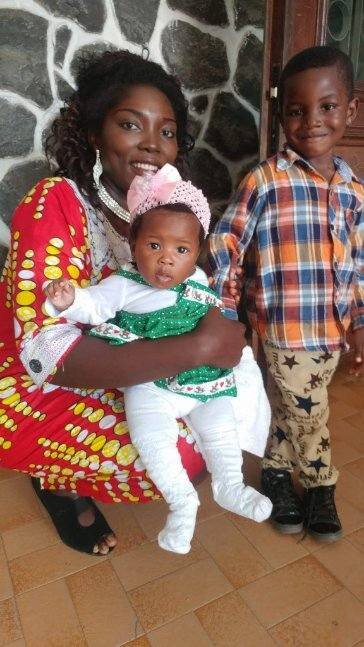

Azaah spent eight months in the detention center, getting out in the late summer of 2019. He now works in a factory in Denver doing quality control work. His family is still in Cameroon, but he recently received paperwork advancing the process for them to come join him. He hopes they’ll be in Colorado within just a few months, making his life in this state even better.

“I love the people that I'm with here right now. I love them so much, but I miss Africa so much too. And I miss my family too, so much,” said Azaah. “But I think that I love my life too … I love my life more, so I have to be alive.”

To find out more about the CIJF or to donate, you can visit their website.

Julio Sandoval is a multimedia journalist with Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at juliosandoval@rmpbs.org.

Amanda Horvath is a multimedia producer with Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at amandahorvath@rmpbs.org

Related Stories