Cheap Land | The separation and the atonement

“Once an entire continent lay sunny and unknown with no names on its face, a vast Unity of ignorance. The fragmentation of Unity began with the first map and continued with every step of the European seizure, every increment to recorded knowledge… the record was one of a gradual dispelling of the mists, a gradual clarification of the roil of speculation, superstition, guesswork, wistfulness, fear, and misunderstanding.”

- "Beyond the Hundredth Meridian," Wallace Stegner, 1953

In "Beyond the Hundredth Meridian," historian and novelist Wallace Stegner foreshadows our present-day natural resources reckoning as a settler-era conflict between two ideologies: a racially motivated and highly romanticized westward expansion fueled by Manifest Destiny and epitomized in the character of Colorado’s first Territorial governor, William Gilpin; and the ecology-savvy realism in Major John Welsey Powell, a Grand Canyon and Colorado River expeditioner for whom Utah’s now-syphoned Lake Powell is named.

As the human-formed Lake Powell reservoir drips to a halt, revealing Native American cliff dwellings, areas of cultural significance and more, one wonders what Powell himself would say half a century after the damming of the Grand Canyon. While Gilpin and his partners privatized land grants and made boisterous claims advertising the near-limitless availability of Western water resources, Powell forewarned over-appropriation, inter-state battles, and irrecoverable depletions. His heed was virtually ignored.

Plans to irrigate the high desert went unfulfilled throughout settlement as over-allocated resources competed with growing demand.

Throughout most of the West, an intense marketing campaign of cheap land and plentiful water created 175 years of growth-oriented settlements that are now atoning with reality. Having been sold a complete vision of the West, water users today — all of us — are stagnant in coming to terms with over-allocation, misuse, drought, climate change, rights discrepancies and age-old competing value systems. We collectively ride the wave of available water — the source of all life — yet still conjure visions of everlasting kitchen faucets, food that never stops growing, and cities and suburbs that can expand forever.

Around the state, agricultural subdistricts, faced with exponential cost and limited availability, have been experimenting for decades with irrigation restrictions and solutions. In some places, subsurface well rights are retired. In others, surface rights from retiring operations are purchased in exchange for continued well use — all in an attempt to recharge, or simply stabilize, water sources for local production.

At the same time, the Colorado River — responsible for 1/12 of the national economy — is evaporating before our eyes. In Fountain, Colorado, developers requesting construction of new residences without available water rights are seeking permissions to literally tap into Colorado Springs’ water supply — 80% of which comes via a 200-mile pipeline from the depleted Colorado River. (In 2021 Fountain halted development until water could be secured.)

Meanwhile, officials and experts consider shutting down Lake Powell forever before a dead pool occurs, removing the dam container to allow the rapidly diminishing waters to flow hundreds of miles to join storage in Lake Mead, Nevada.

The Rio Grande weaves through the high desert of Costilla County, creating a natural border with Conejos County to the west.

In the high desert of Costilla County, many of the state’s first permanent settlements still carry the weight of disparity between an idealized West and the actual availability of water resources.

Native American inhabitance and Spanish rule preceded settlement here by thousands of years. Mexican rule from 1821 to 1848 brought the first lasting colonies to what is now Costilla County. The million-acre Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, issued to Charles Beaubien in 1844, hinged on access to the mountain resources like water, timber and firewood, as well as hunting and grazing lands.

[Related: Visit a map of regional stories from Costilla County here.]

The southern Sangre de Cristo Land Grant boundary falls between the present-day towns of Costilla and Questa, New Mexico.

Systems clashes raged at once across what is now south-central Colorado and northern New Mexico as the area shifted to become part of the United States of America post-Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848). Predominantly Anglo prospecting companies immediately worked to commodify pre-existing, community-oriented land and water systems of thousands of first-wave Native American, Mexican, Spanish, and Genizaro settlers. Early estate managers were tasked with subdividing the former land grant into private estates, and moved to evict settlers, whom they deemed “squatters.” Yet they were careful not to remove so many that there would not be customers for their stores, and a labor force for mining, planned agricultural development, and railroads.

Prior, the area’s first settlers lived within their means. Initial land and irrigation systems of the mid 1800s were calibrated to subsistence farming scaled to available ecology. Settlers dug ditches by hand from natural streams called acequias. The water raised crops, livestock and civilization across a land system rooted in gravity and nature. Long-lot lands called varas were instilled, granting each landowner equal riparian areas and foothills per an ancient community land management system. Each land holder utilized scrubby sage lands known as extenciones for off-season grazing and stock moving and had access to the communal ditch systems to irrigate fields.

[Related: Watch a presentation about Culebra Watershed history by Joel Nystrom of Colorado Open Lands]

Post-Treaty, an eastern influx brought new metrics: the PLSS (Public Land Survey System) land grid, major diversion of streams, building of reservoirs, and construction of vast canal systems meant to store and utilize water at the scale of the dreams of man.

In Costilla County, the charge was led in part by Gilpin, who with a team of investors named the Freehold Land and Emigration Company took on title of the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant for $15,000 in 1864.

Like most major figures of the West, Gilpin was entrenched. He and his brother served concurrent Presidents (Gilpin was appointed by Andrew Jackson at West Point; his brother was attorney general under Van Buren). Gilpin slept in the White House throughout March of 1861, Wallace Stegner writes, to protect President Lincoln as he took office. By the end of March, Lincoln appointed Gilpin as first territorial governor of Colorado, and Gilpin traveled west to take his post.

But Lincoln fired Gilpin within the year after soldiers organized for the Union Army without federal consent to support the Battle of Glorietta Pass surfaced in Washington to demand the wages and reimbursements Gilpin had promised them.

Gilpin was not deterred. Having learned the lay of the land, he dove headfirst into real estate and prospecting, purchasing the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant in 1864 along with other land grants and large land claims. Neither Stegner nor history recall Gilpin’s regard of Western resource allocation with grace, and his paper trail is seasoned with fraud: water, land, trees, minerals, metals, diamonds. Gilpin took advantage of the slow news cycle and relative isolation of his land holdings to maintain the core of his marketing: cheap land, endless water. An eastern Quaker turned political orator from Missouri, Gilpin embraced semantics and relied heavily on the fact that first-person accounts from the ground he was hocking to immigrants were few and far between.

For every Edison, there is a Tesla. While Gilpin filled in the blanks toward a personal end, Major Powell stressed discovery and unity in an unknown landscape. Comparatively, Powell’s ethos of western water resources was studied, tempered, and skeptical: a glass-is-already-half-empty approach. “Instead of preaching unlimited supply and unrestrained exploitation,” Stegner writes, Powell “preach[ed] conservation of an already partly gutted continent and planning for the development of what remained.” According to Stegner, Powell endeavored to study, classify, and document Native American oral histories and languages before they were “obliterated by the tide of Gilpin’s settlers.”

The 100th meridian, an oft-acknowledged longitudinal land boundary, came to define post-Treaty lands as a natural division of precipitation between the fertile, afore-settled east and the dry, barren western landscape. Gilpin and his associates worked hard to create a counter-narrative to the desert sage brush, circulating lofty brochures and advertisements aimed at enticing European settlers. Powell, meanwhile, spent his career attempting to unravel impractical claims about the ease and everlastingness of water in the desert west.

Abandoned water infrastructure built by Costilla Estates as part of an agricultural development plan in the early 1900s.

The Freehold Company employed proxies to survey and prospect water, timber, and mineral deposits, and courted foreign investors. Powell advocated that development should follow ecology — not the other way around.

As the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey, Powell’s guidelines more closely aligned with the pre-existing vara land settlement system: highlands to be used for timber, middle lands for grazing near waterways, and irrigated lands chosen in proximity to available water. (A mere 2% of the lands proposed for irrigation in the west were within range of Powell’s recommendations.) Powell urged to keep the ecology intact, and for state boundaries to follow natural watersheds.

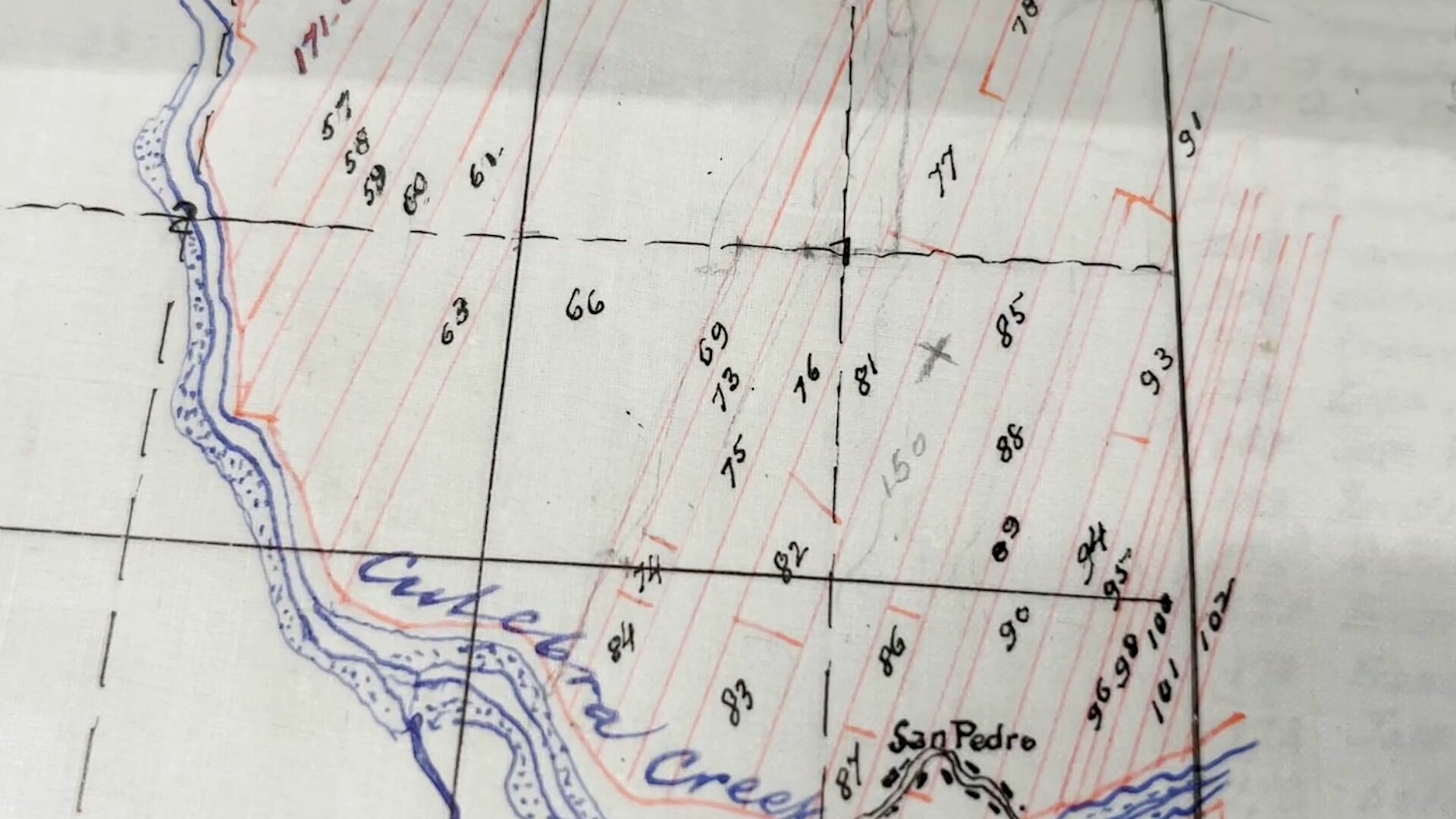

A 1894 Costilla Estates drawing depicts an early attempt to fit the Mexican and Spanish vara land system within a USA-PLSS grid – a discrepancy still in court today. Map courtesy Edmond Cornelius Van Diest Papers, Map Folder 17, Colorado College Special Collections, Tutt Library.

The Freehold Land and Emigration Company read Powell’s advice upside-down. In creating Costilla County’s first subdivisions — the Costilla Estate and Trinchera Estate — the investment firm closed the commons, ousted local landowners, and began a pointed campaign to remove settled lands from original families through a series of newly minted legal requirements. Developers superimposed the PLSS grid system over the unique vara layout, creating odd leftover parcels of land that are still contested in court well over a century later.

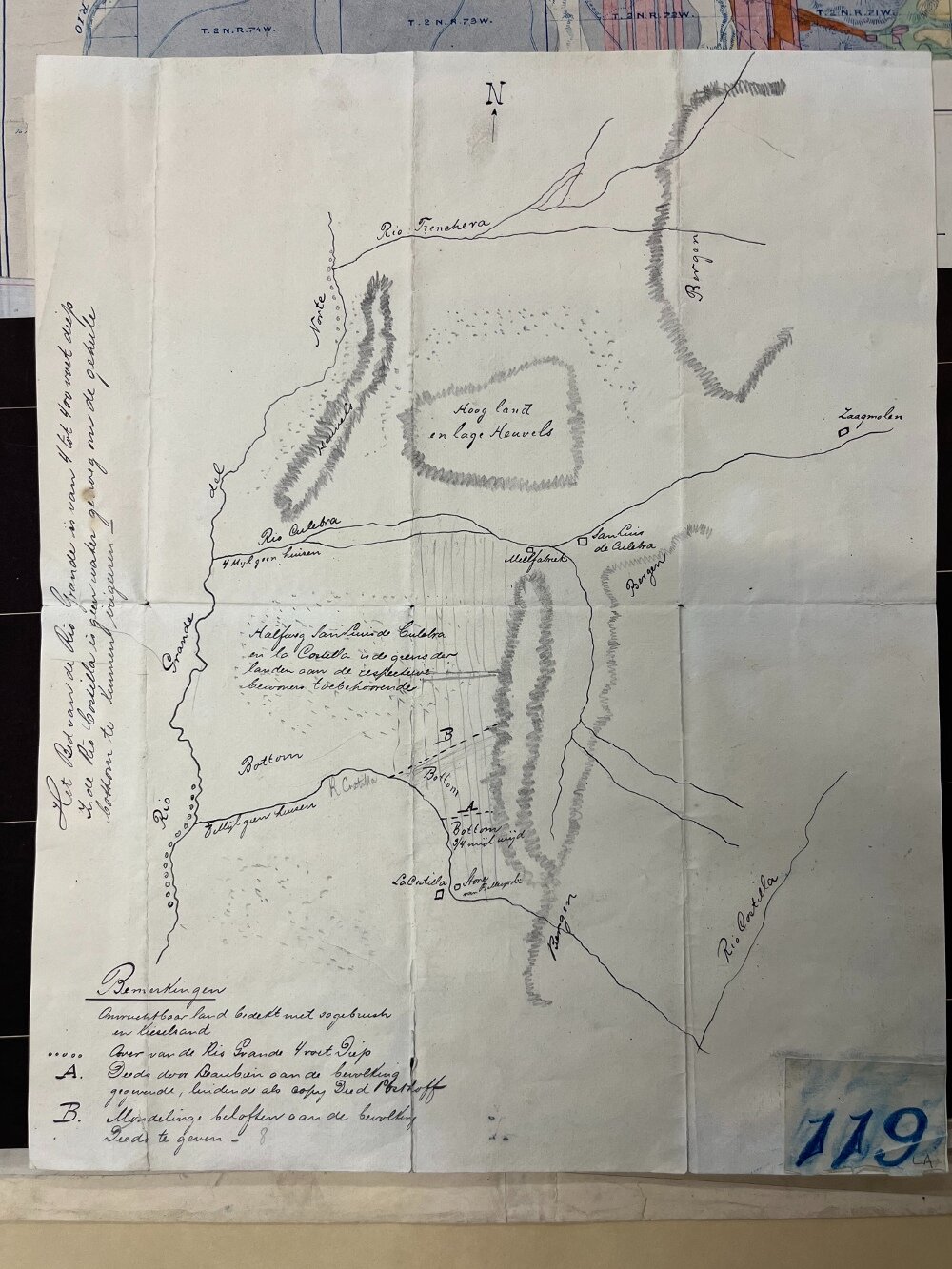

An early map created by Dutch investors, in Dutch, shows pre-diverted waterways including the north branch of the Culebra River intact. Map courtesy Edmond Cornelius Van Diest Papers, Map Folder 17a, Colorado College Special Collections, Tutt Library.

The estates mostly followed watershed boundaries, punctuated by the chopping of rivers and diversion of streams (thus nimbly eschewing downstream compacts for future generations). In one exception, Colorado’s southern line was at first drawn with the Culebra watershed intact. But in 1868, during a resurvey to establish the Trinchera and Costilla Estates, the first land grant settlement and southernmost Colorado town of Costilla was “given back” to New Mexico, thereby separating Costilla Creek from its fellow tributaries with an imaginary line and a spaghetti of regulations that raise the hair, voices, and sometimes fists of generations since.

Some highly prized settlers did make it to these vast estates — but not enough over time. As European settlement waned, the Freehold Company shifted marketing to specific religious affiliations they hoped could fill their plat maps and town plots. Like Gilpin’s Union soldiers, settlers arrived to cash in on what was promised to them. And like Gilpin’s soldiers, many left with empty pockets.

All the while, Powell attempted to convey common sense in irrigating the desert. “You are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights,” he stated in 1883, “for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.” As director of the U.S. Geological Survey from 1881 to 1894 — the year of Gilpin’s death — Gilpin’s precise Costilla County estates are likely among those Powell was speaking to.

Early Marketing of the Costilla Estates. Edmond Cornelius Van Diest Papers, Box 50, Folder 233, Colorado College Special Collections, Tutt Library.

In Costilla County, Gilpin’s successors engaged federal subsidies to build water infrastructure to increase agricultural production of unirrigated lands. Sagebrush turned to farmland via an intricate system of holding ponds and reservoirs, and dozens upon dozens of miles of canals. Constructed at length through the early 1920s, some of these systems never saw a drop of water.

Abandoned water and railroad infrastructure east of the Rio Grande on the former Costilla Estates.

Despite the limitations of the desert West, many farmers and ranchers and their families have thrived here for generations, in stunning displays of hard work, adaptability, ingenuity, and grace. Some make do with little — and sometimes barely make do. Others are carried by the winds. The ghost of Gilpin's initial marketing plan still lingers here, as new arrivals answer the call of cheap, subdivided prairie lands. Only now, with no water attached.

With Gilpin’s dreams on one shoulder, and Powell’s reality on the other, our future works toward balance.

This article is part of a series. “Colorado Voices: Cheap Land Part One” premiers on Rocky Mountain PBS and our YouTube Thursday, Feb. 9 at 7 p.m. “Cheap Land Part Two” airs Feb. 16 at 7 p.m.

Kate Perdoni is a senior regional producer with Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.

Related Stories

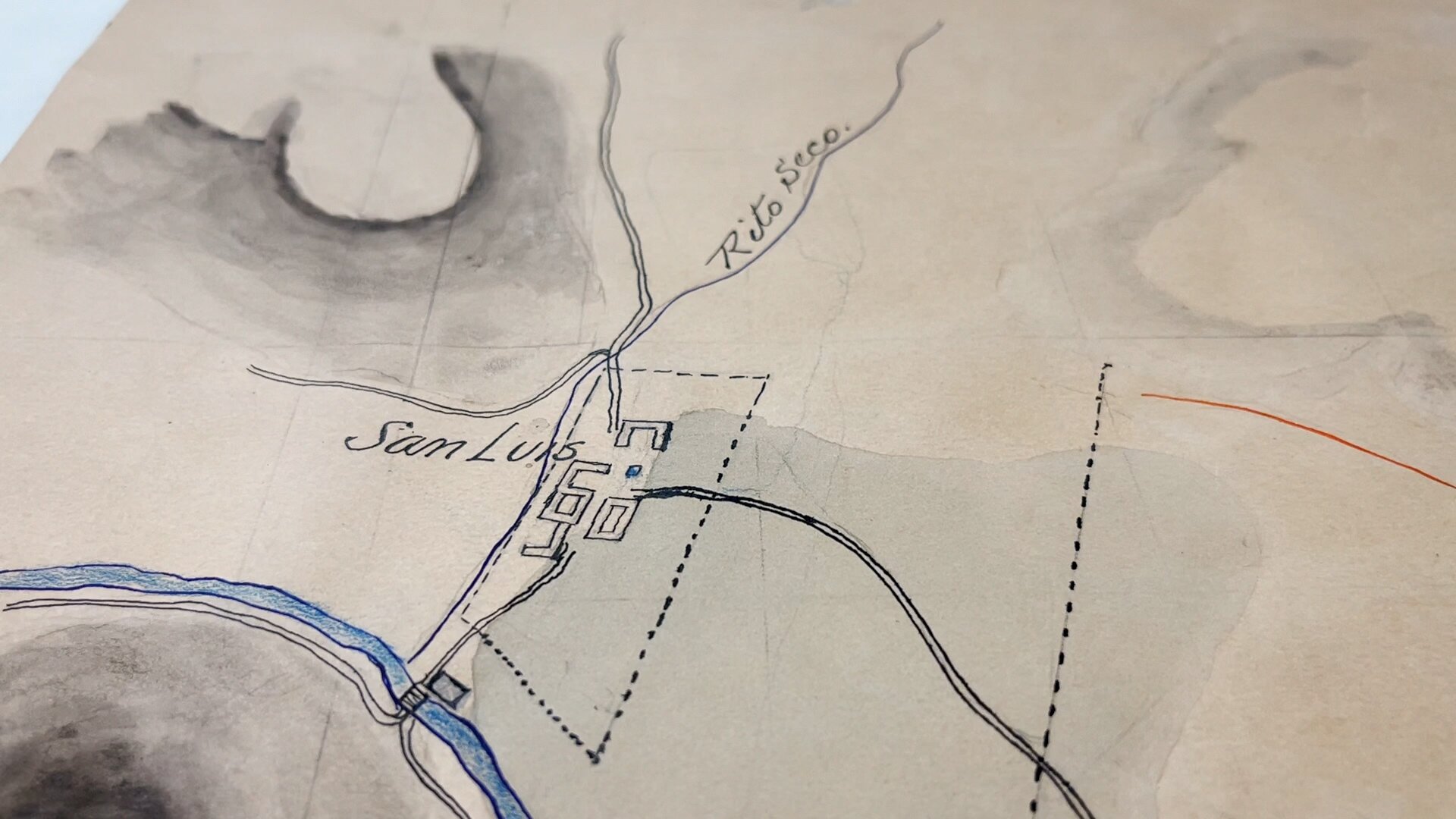

First: The early land grant settlement of San Luis today. Second: An early hand-drawn map of San Luis depicts water resources. Map courtesy Edmond Cornelius Van Diest Papers, Map Folder 17, Colorado College Special Collections, Tutt Library.

Costilla Estates surveyed and prospected Costilla County’s mining, railroad, agricultural, water and land systems in order to bring a second wave of settlers from Europe and the east. Here, representatives for the Costilla Estates are pictured throughout the Estate, 1894-1911. Photos courtesy Colorado College Special Collections, Tutt Library, Edmond Cornelius Van Diest Photograph Collections, PP 82-11a and PP 82-10s.