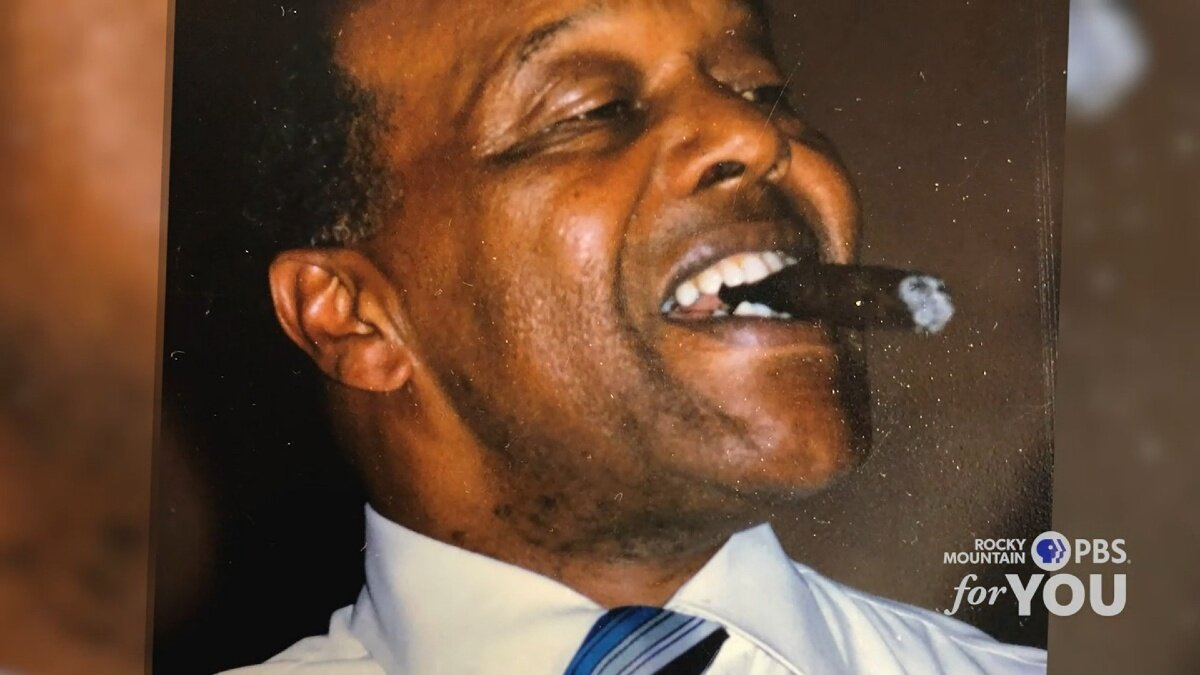

Charlie Burrell, the 'Jackie Robinson of Classical Music,' turns 102

Thanks to the generous support of the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation we bring you this story on musician Charlie Burrell.

Barrier-breaking musician and Denver icon Charles Burrell turned 100 years old today. The jazz and classical bass player became the first African-American member of a major American symphony, which is why he is often referred to as the “Jackie Robinson of classical music.” Like Robinson, Burrell battled racism and prejudice to break into an all-white profession. And with decades of performances and inspiring countless musicians, Burrell put together a career that can only be described as legendary.

To find the start of this storied career, we have to go all the way back to the early 1930s. A 12-year-old Burrell was listening to his Crystal radio when he came across a broadcast of the San Francisco Symphony. The conductor was the renowned Pierre Monteux. Listening to the symphony’s performance changed Burrell’s life. In that moment, Burrell—who was taking lessons on the string bass and tuba at the time—decided to become a professional musician.

Last summer, Burrell spoke with KUVO’s Carlos Lando to reminisce about his magnificent life, career, and influence.

Burrell also helped launch the career of his niece, five-time Grammy Award winner Dianne Reeves, and taught the legendary pianist and composer George Duke at the San Francisco Conservatory.

In 1999, Burrell retired from the Denver Symphony at age 79. He continued playing music well into his 90s, and inspiring millions of listeners.

Happy birthday, Charlie Burrell.

Born in Toledo, Ohio in 1920, Burrell grew up in Detroit. Or, as he called it, “Destroy.”

Burrell graduated from Cass Technical High School in 1939 and continued his education in Michigan. “I went to audition for a college called Wayne University there and I've had so much good training at Cass Tech,” Burrell explained, “and so they let me into their university without an audition, and that was the beginning of my big career for life.”

But the path wasn’t easy.

“Coming up to graduation I was called in a room by one of the men who ran the school and he was commending me and praising me on my ability and what I had done and I almost got tears in my eyes cause it was so great,” Burrell recalled. “And then he pulled the plug on me. He says, ‘I'm 40 years old and as long as I’m here there’ll be no negroes in the music department in any of the public schools.’ And that just blew my whole thing.”

Burrell was 16 years old when he first realized that his musical talent would not make him immune to racism or hatred. But he continued to pursue his passion while working odd jobs at restaurants and, more importantly, night clubs. That’s where Burrell really learned to play the bass in his own unique style.

“That was the beginning of...a tremendously fruitful career for me,” Burrell said.

Burrell’s first orchestral career opportunity came from the then-Denver Symphony (now called the Colorado Symphony) in 1949. He was the first African-American to receive a permanent contract with a major American symphony, earning him the nickname “The Jackie Robinson of classical music.”

In 1959, Burrell was hired by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. At his first rehearsal, a guest conductor entered the stage. It was Pierre Monteux, the conductor he listened to as a child.

“When I first walked out on the stage, and the conductor introduced me to the orchestra, they stood and gave me applause,” Burrell said. “And I cried because I’d never been treated so well in my life.”

After five and a half years in San Francisco, Burrell returned to Denver and embarked on a 30-year journey with the Denver Symphony. Burrell’s mother, Denverado, was born in Denver. He said she was a “saint above saints.”

As many people in Denver know, the Five Points neighborhood is the place to go for jazz music. It was Burrell’s favorite neighborhood, too.

“The best soul food I’ve ever had in my life was on Five Points. Where Wells Fargo is was called The Ritz,” Burrell said. “And that was the best place in the world to get what we called “grits at The Ritz” every Sunday morning. And [the owner] would make homemade rolls and if you didn’t get there before 7 o'clock, you didn't get any because she was sold out. And by about a quarter to seven, she would always close the doors and say, “That's it, boys. I have more customers to serve.” And we were having six and eight rolls a piece with butter and good coffee.”

Five Points hold a special spot in Burrell’s heart. Not just because of the food back in the day, but because he performed at the Rossonian Hotel. He was the top on-call jazz bassist in Denver for more than 50 years and performed with music legends like Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker, Gene Harris, Ben Webster, and Sarah Vaughn.

Burrell is featured in L.D. Olken’s 1999 documentary “Jazz in Five Points,” part of the Rocky Mountain Legacy series aired on Rocky Mountain PBS.