'Chained Voices' art exhibit aims to show a different side of Colorado prisoners

DENVER — Andrew Draper imagines a world where everyone is seen and everyone’s voices are heard, a world where no one is ignored — including people who are incarcerated, like him.

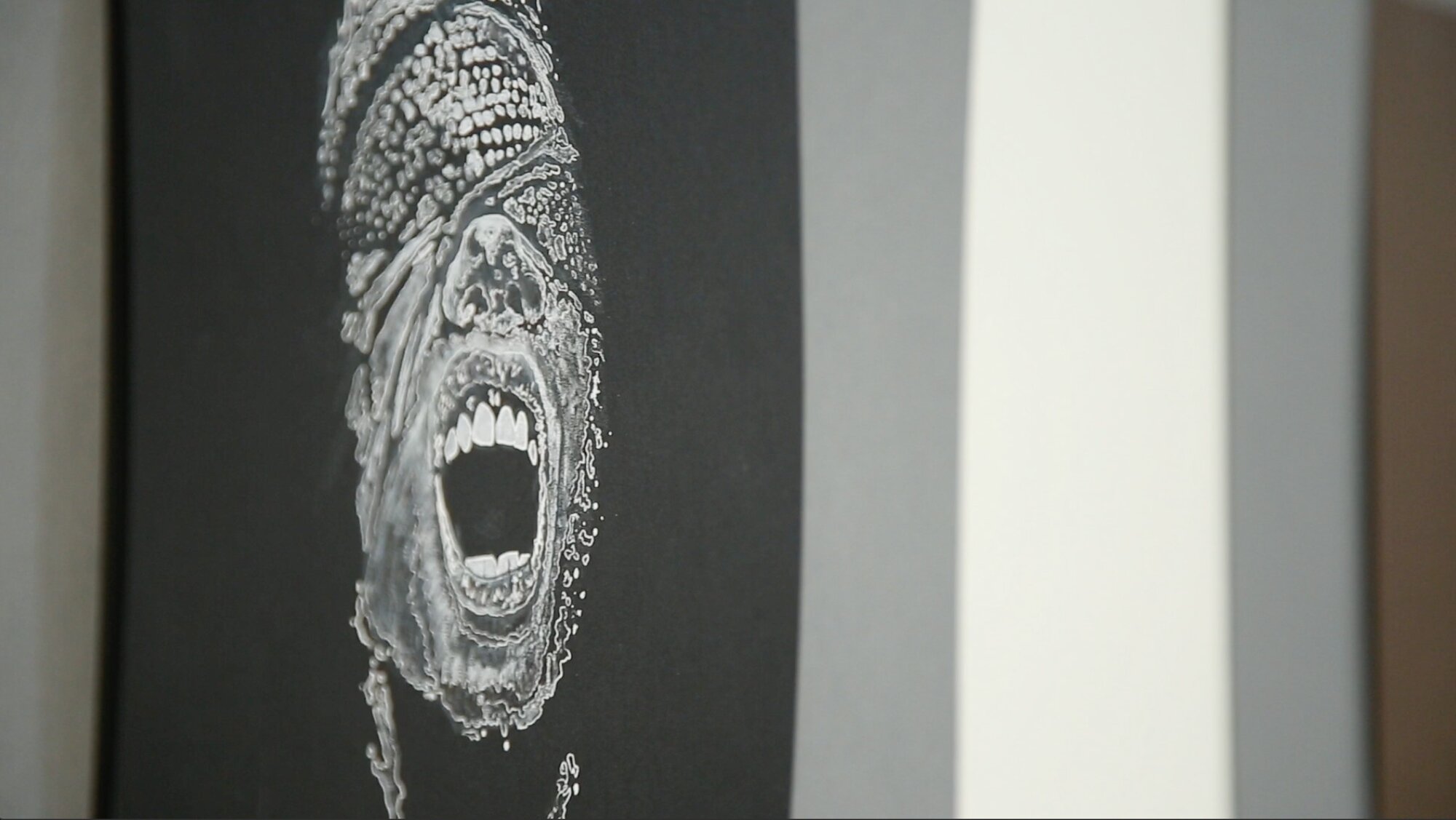

Draper, who considers himself an artist, helped curate the Chained Voices exhibit now showing in the McNichols Civic Center building in Denver's Civic Center Park. The show includes 450 pieces of art in the gallery and online, created by more than 200 incarcerated people from prison facilities across Colorado.

“It represents voices," Draper said. "It represents people’s voices who feel as if they scream but are never heard. It feels like they’re screaming in the wind. That’s what the Chained Voices art show represents. It represents humanity. It represents the dark side of life, and everything that’s beautiful in the world.”

Draper continued: “A lot of artists that I speak with — and not just those who created art for Chained Voices —but just in general who are incarcerated, they feel as if they don’t have a voice and they feel as if no one is willing to listen to them and the Chained Voices art show does provide an outlet for the people to get that emotion out."

Draper is incarcerated at the Sterling Correctional Facility and is 15 years into a life sentence for first degree murder.

“There’s not enough that can be said about the victim’s side of things," he said. "Especially when we’re talking about incarcerated people, we’re talking about crime and we’re talking about people who are hurt; we can’t do that without speaking about the victims and the victims' side of it.”

Chained Voices is one of several programs offered in the Colorado Department of Corrections through the University of Denver Prison Arts Initiative, co-founded in 2017 by assistant professor Ashley Hamilton. “Not wanting to dismiss the harm and not wanting to disrespect what has happened [to victims] but also: there are a lot of incarcerated folks who are committed to creating restoration, to creating rehabilitation and healing," Hamilton explained. "There are many folks inside who are hungry for change and want to live lives that feel restorative that are healed or that are in the process of healing."

Hamilton believes the Chained Voices art show gives the general public a chance to see a different side of incarcerated people.

“I’ve gotten to watch [incarcerated] people, in soft skill ways, grow and heal and change and become leaders, and gain stronger communication and be able to deal with conflict in healthier ways, and restore and renew relationships in their lives with loved ones and in the community and even reaching out to have restoration with victims and survivors," she added.

Draper wants people to know that he is a whole human being, not just someone who is in prison. And he says the rehabilitation process is something he works on daily.

“The rehabilitation of oneself comes from the drive to be better than what you once were," he said. "And that can’t be something that exists in pieces. It can’t exist today but not tomorrow. This has to be something you do everyday: everyday you have to wake up and you have to desire to change; not just to change, but to be it and manifest it. I think the arts lending to rehabilitation is … it’s key, right?”

So far, $11,500 worth of art has sold since the exhibition opened in June.

"I think this has been the most successful selling show we've ever had," said Shanna Shelby, the chief curator with Denver Arts & Venues. "Ninety-five percent of these pieces have sold. We've never had that happen before."

The proceeds go directly to the incarcerated artists who, according to Draper, will likely use the funds to buy more art supplies. The exhibit lasts until Aug. 20.

“Before I came to prison I never sold a piece of art. I never sold a piece of art to anyone. I sold drugs, that’s what I sold, things that can be taken away because they were ill-gotten" Draper said. "This, however, is not-ill gotten. This is real. This is something you can put on a resume, something that can move the emotions of another human being. This is something that no one can take away from you."

Dana Knowles is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at danaknowles@rmpbs.org.

Julio Sandoval is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at juliosandoval@rmpbs.org.