From Little Rock to Denver, Carlotta Walls LaNier continues to fight for education

DENVER — Carlotta Walls LaNier, who made history as the youngest of the Little Rock Nine — the Black students who integrated Little Rock Central High School in 1957 — learned to value education and the role it plays in speaking truth to power from her great-great-grandfather’s example.

Hiram Holloway, LaNier’s ancestor who was of Spanish and Native American descent, recorded his eyewitness account of seeing enslaved people being auctioned off in Atlanta, Georgia, once he was an elder for the Works Progress Administration’s 1937 Slave Narratives historical project.

Holloway’s recounting of the inhumanity of the slave trade became part of the United States historical record and proved vital in the preservation of an accurate history of life in the antebellum South for people of color.

“[My great great grandfather] recognized the need for change to take place and for people to be educated, and he brought that thought to his family,” said LaNier.

The respect for education and its role in cultivating change led LaNier, at 14, to enroll at Little Rock Central High School.

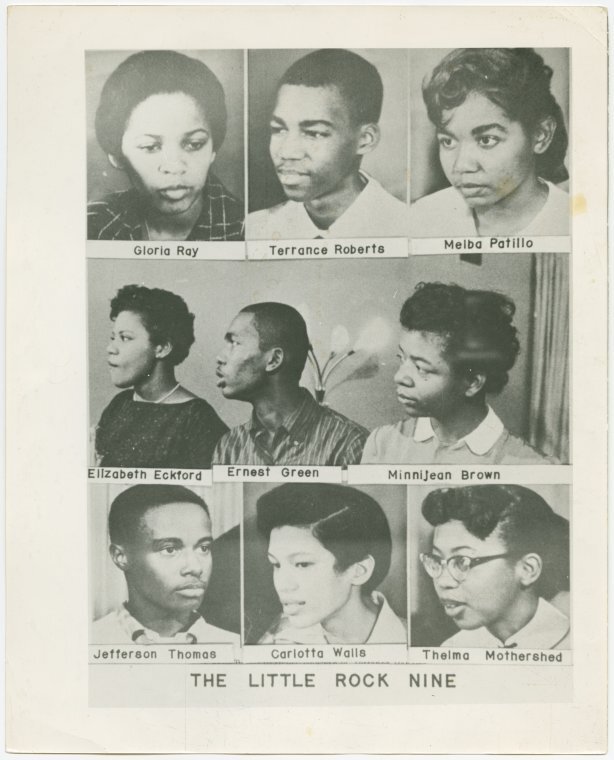

LaNier and eight other students, dubbed by the media as “The Little Rock Nine,” became the first Black high schoolers to racially integrate the all-white school just a mile from her home.

Their story became national news when Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the students' entry to the campus. President Dwight D. Eisenhower countered by ordering federal troops to safely escort the nine students into the school.

Carlotta LaNier was the youngest of the Little Rock Nine.

Photo: New York Public Library Digital Collections

“I didn’t think at this age in my life that I would be talking about my high school years, to be honest with you, but it is what it is,” said LaNier, who is now 82 and worked for decades as a real estate agent in Denver.

Her high school years formed the basis of LaNier’s 2009 memoir “A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School,” her own narrative of life in the segregated South.

“[Writing the book], it was really an opportunity for me to tell my story, to leave a legacy for my family as to what made me want to go to Little Rock Central High School,” said LaNier. “Also, the foundation that I came from, I’m hoping to pass on to my children and grandchildren.”

Today, seeing some of the same cultural forces that suppressed Black history and access to education when she was a girl gaining ground nationwide, LaNier has released a young adult version of her book.

LaNier’s strong belief in the power of a history and civics education prompted her to re-tell her story with new urgency in light of leaders such as Florida Governor Ron DeSantis announcing that educators there, for example, will not receive any funding if they support studies in critical race theory or systemic oppression.

“It’s pretty obvious to me by looking at who is representing us in congress and so forth that they didn’t get the memo to take history and civics to understand how this country was built,” LaNier said.

Having made history herself, LaNier is wary of it repeating. In 1957, 500 Black students lived in the Central High School area, and 80 had shown interest in attending Little Rock Central. The Little Rock School Board interviewed those 80 students ahead of the effort to desegregate and, ultimately, 17 students were chosen.

By the time she started school, that number was down to just nine.

“It was the journalist that pretty much named us [the Little Rock Nine], not that we went in with that in mind, none of us did. All we wanted to do was get the best education possible, period,” said LaNier.

Although it was a victory for LaNier to get accepted into Little Rock Central High School, she said racism took out all the fun of being a teenager. During LaNier’s time at school, she endured racism and racial slurs being yelled at her, among other disturbing treatment.

“I felt good about being at least able to go to school,” LaNier said.

“Everyone was two and a half to three weeks ahead of me. I was going to have to do that old thing that needed to be said and done, that I grew up with, that you got to be two and a half times to three times better than a white person,” she said.

LaNier said the Black parents were the real heroes because it took a lot for them to allow their children to go inside a hateful environment. LaNier said the parents, her own included, feared their children would not come out alive.

“[The parents] could have said you are not going back to school. My mother greyed that year,” said LaNier.

LaNier holds a photo of her with her family.

Photo: Lindsey Ford, Rocky Mountain PBS

She didn’t realize the toll it must’ve taken on her parents until she became a mother herself. LaNier and her husband, Ike LaNier, have two children, son Whitney and daughter Brooke. LaNier is also a grandmother to 14-year-old Reese LaNier and 9-year-old Jalen McClean.

LaNier’s mother, Juanita Walls, now 98, lives with her in Denver.

After graduating from Little Rock Central in 1960, LaNier studied at Michigan State University for two years. Later, she moved to Colorado and earned a bachelor’s degree at the University of Northern Colorado.

LaNier remained in Colorado, where she raised her family and continues to work as a real estate broker to this day.

“Once you decide to do something you see it through. I was taught that at home,” she said.

Over the years, LaNier has maintained an active voice in creating positive change, serving on the University of Northern Colorado board of trustees and as a Park Hill Methodist Trustee and the Colorado AIDS Project.

“I believe in giving whatever you might have to your community to make it better,” she said.

LaNier not only has high hopes for Black youth but for all of those who have been oppressed, including other racial and cultural groups.

“All immigrants who have come to this country, I want them to be proud of who they are,” she said.

“There are too many factors out there to keep a certain group of people down, and with that I want them to be able to understand what is happening to them and that they have a voice, and to use that voice.”

Lindsey Ford is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Lindseyford@rmpbs.org.