'Breakthrough' program aims to empower Colorado prisoners, lower recidivism rates

CAÑON CITY, Colo. — Inside the Centennial Correctional Facility in early December, inmates lined up on either side of the entrance and held their hands out to high five volunteers, friends and families as they arrived for a rare occasion at a maximum-security facility: a graduation.

A total of 16 inmates became the facility’s first graduates of the Breakthrough program, a nonprofit curriculum created in 2017 to equip incarcerated people with reintegration skills.

“All the volunteers that came up and showed us all so much love, kindness, empathy and compassion and it's really overwhelming,” said David, who was part of the graduating class.

Since its inception, Breakthrough has expanded to four other correctional facilities in Colorado: Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility, Centennial Correctional Facility, Colorado State Penitentiary and the women’s La Vista Correctional Facility.

The ceremony at Centennial marked the inmates’ completion of a 32-week course called “The Challenge” dedicated to character development, job readiness, reentry, and entrepreneurship skills.

Participants in “The Challenge” are all convicted of felonies and have sentences that range from a couple years to life in prison. To join the program, students undergo an application process designed to measure their commitment to the program.

“When I first joined, I didn’t really know what I was stepping into,” said Francine, who graduated in 2022 from the program at the La Vista Correctional Facility, a medium-security prison in Pueblo.

Many of the exercises start with empathy to connect participants and volunteers. In an exercise called “step to the line” participants and volunteers line up facing one another and if a statement is made that they can relate to, they each step forward.

From statements like, “I grew up with two parents,” to “I’ve been in the prison system since before I was an adult,” students and volunteers learn about similarities they share and how just one change could alter their life’s trajectory.

Francine, a peer facilitator, enjoys a rare Chipotle meal

Photo: Peter Vo, Rocky Mountain PBS

“As I proceeded to be in the program, I found myself just surrounded with so many people who actually show much compassion and love,” said Francine, who is now a peer facilitator.

Peer facilitators are program graduates who offer support to the new class. They help with administrative tasks and use their experience to mentor others.

Francine credits the program for changing her outlook on how to approach life and correct mistakes she’s made. She has been incarcerated for 13 years following a conviction for assault and kidnapping.

“I’m not just thinking of myself, I’m thinking for my community,” she said. “We’re sent to the Department of Corrections and somewhere down the line we have to correct what got us here to prison.”

On their last day of the program, the men at the Centennial Correctional Facility presented the business ideas that they had been working on.

The ideas ranged from a laundry delivery service to a supportive reentry program called “Homeward Bound” that would equip people with phones, housing and resources when they are first released from prison.

Participants present their business pitch: “Progress Paddle Sports Worldwide”

Photo: AJ Campli

After a five-minute presentation, the volunteers voted on the most practical idea and awarded each member of the winning team, the minds behind “Homeward Bound,” $300.

Once they finished the business pitch, students officially graduated the Breakthrough program and put on their cap and gowns. For some of them, it was their first time in a cap and gown since middle school. For others, it was the first time they had seen their families in years.

“It was moving for people to see their family, who they haven't physically handled in over ten years,” said Fred, one of the peer facilitators for the graduating class at Centennial.

Many of the inmates, who cried and cheered for one another as they received their diplomas, were seeing their kids grow up as well, Fred said.

“And so that is an experience that can’t be undone to a person experiencing accomplishment at the same time,” he said.“Because as much as he wants to appreciate his moment, he also wants to share it with his family and his loved ones.”

Nathan, the class speaker, spoke with sincerity about the group’s tense relationships at the start of the program and the brotherhood that has come out of it through all the work they’ve done together preparing pitches and job interviews.

“We all work to overcome this system, and be the statistic that is given to us,” Nathan said. The men embraced one another and broke out into chants as they celebrated and threw their caps into the air.

“This is the first thing that I’ve chosen to do,” said David, another graduate. “I committed to myself and I held other people to commit.”

David has been in and out of the prison system since he was 13-years-old. He is now 41 and serving a life sentence.

“There’s a big fall in the system,” David said. “I believe people aren’t taught the skills while incarcerated to get out and lead a normal, productive life.”

These skills range from entering the workforce to learning how to live in society. Many incarcerated people have been in prison so long or from such a young age that tasks such as getting IDs, learning how to write a resume and figuring out how to use a computer are all foreign to them.

Learning the skills to speak publicly and working with his fellow teammates to create a business in the classes, were just some of the things that changed David’s outlook on his sentence, even if he might not ever be released.

“I’m living my best life that I’m making for myself and I’m dictating my life now,” David said. “I'm going to do what I feel is right for me and what I know is right. And I'm going to walk the path that I want to walk. And as long as I know what I'm doing right, I'll always be okay with it.”

David continues to work on his passions, making art for people in the prison and applying to be a peer facilitator for the next cohort of Breakthrough candidates.

Fred is also serving a life sentence with no possibility of parole, but that doesn’t stop him from continuing to educate himself and give back as a peer facilitator.

He’s been incarcerated since he was 18 and is now 40. His faith and pursuit of education keep him going, Fred said.

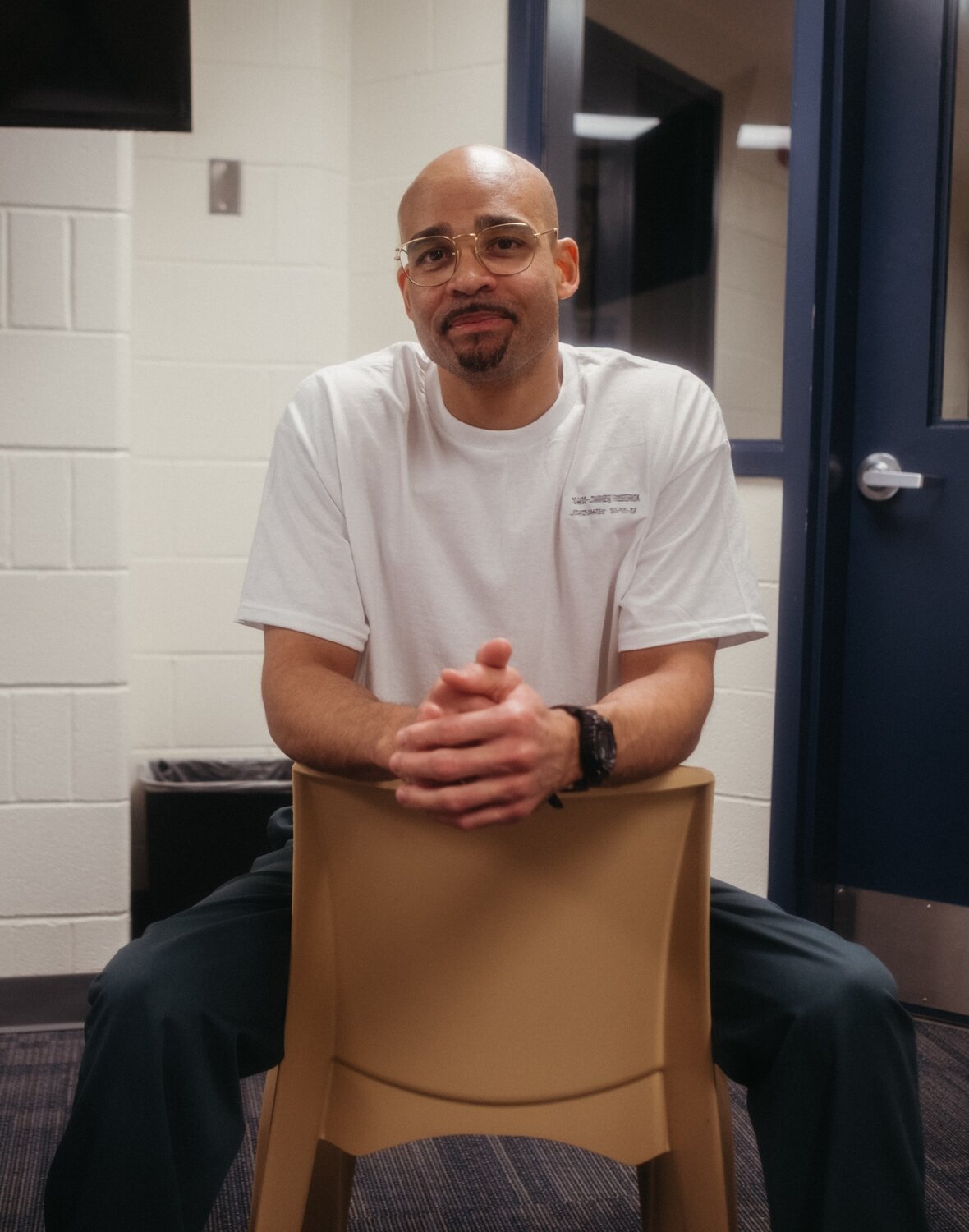

Fred, 40, has been a prisoner for more than half of his life.

Photo: Peter Vo, Rocky Mountain PBS

“Opportunity only lends itself to those who really give themselves to it because there's no opportunities for people who are sitting around in their cars,” he said. “So I just had to make my presence on my own. And so the graduation was a bridge. It was a bridge to other things that I could realize other success in my personal quest.”

Fred used the program as a way to learn skills to apply to other jobs in prison that require a resume and hiring process.

Jobs for prisoners tend to pay between $0.14 and $0.63 per hour at the national level. Even with low pay, the demand for jobs remains high for inmates because it’s the only way they’re able to earn money outside of having family send funds. Many of these jobs center around support for the prison such as custodial, kitchen and maintenance work.

According to the Colorado Department of Corrections, each inmate, “has an inmate account which they can use to purchase canteen items including phone time, stamps and writing materials, food, clothing, and hygiene items.”

David uses his wages to fund his artistic expression. He sells art to other inmates and staff and, in turn, buys pencils to continue working on his art.

“I draw anything that I think brings light to people,” David said. “I like to draw stuff that I feel that's meaningful for me, something that I want to be beautiful or, you know, that inspires me to try to get out,” referring to the possibility of his life after prison.

On the day Rocky Mountain PBS interviewed him, he brought a drawing as a gift to Eboni Nash, who led his cohort during the 32-week program. David credits his transformation and dedication to the program because of the support from staff and volunteers.

Eboni Nash addresses the graduating class as one of the speakers at graduation.

Photo: AJ Campli

Francine does the same, “All of the volunteers and the Breakthrough team just shows up. And every single time they just guide us with love.”

The program exists because of volunteers. They give feedback for business pitches and conduct mock interviews as well as attend the graduation ceremonies.

“We’re bringing people together who might not necessarily ever be in the same room,” said Ashley Furst, the director of business development and community engagement.

Breakthrough volunteers apply and undergo a background check after which they sign up for specific events such as kickoff or graduation.

“I think our society has a bad habit of writing people off when they are at their worst and pushing them down further into a hole,” said Jada Szympruch who volunteered at the graduation event.

“But that's not the aim of this program, in fact it's the opposite,” she said.

Szympruch learned about the program through Nash, who often leads the classes held at the correctional facilities. She said she felt inspired to join because of Nash’s passion for the program and her willingness to help.

“These guys are bettering themselves emotionally, mentally and putting in the work to educate themselves as well. They are pushing the boundaries of what they were told they were capable of in this world, and they are defining what they are worth,” Szympruch said.

Furst initially became involved as a volunteer with Breakthrough. A former inmate, she wanted to go back to prison as someone who could help people who’ve been in the same situation.

“When I was incarcerated, I wish I had someone who had been in my situation come back in and be like, hey, yeah, you made this mistake, but you accepted your punishment, you're doing your time and you can come out and you don't have to be defined by this label,” Furst said.

Furst mentions that many individuals who are released from prison are neglected and the support to help them reintegrate isn’t strong, resulting in high rates of recidivism.

“Where are they living? What is their housing situation? What does your transportation look like? Do you need bus passes,” she said. These are just some of the questions that need to be answered in order to help people reintegrate into society.

In Colorado, the recidivism rate is at 44.9% which is higher than the national average of 37.1%.

“I don't think people realize how our systems aren't structured to reintroduce people into society after being in these facilities,” said Szympruch.

“But these programs try to do that. I think in life, we all make mistakes, and these men are really trying to take ownership and do right by their second chance,” she said.

Breakthrough’s main aim is to lower the rate of recidivism of its graduates.

Two fellow graduates embrace one another after the ceremony.

Photo: AJ Campli

“Right now our recidivism rate stands at 6%,” Furst said.

Since forming in 2017, Breakthrough has had a total of 203 graduates, with 55 of those graduates becoming paroled, according to the organization’s 2022 annual report.

It costs about $61,000 per inmate, per year to detain people in Colorado prisons so by keeping recidivism rates low the Department of Corrections saves money, Furst said.

A new cohort of students will begin “The Challenge” January 23 at La Vista Correctional Facility in Pueblo, where Francine will return as a peer facilitator.

“We need somebody to say, I believe in you, you are worthy,” she said. “You are somebody worth changing and giving a shot. And that's where our transformation comes from, is just having those people who come in and truly believe in you.”

Carly Rose is the journalism intern at Rocky Mountain PBS. Carlyrose@rmpbs.org.

Peter Vo is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Petervo@rmpbs.org.