Local blues legends honor Big Mama Thornton’s legacy

DENVER — December 11th is a big day for the blues and, depending who you ask, for the world. It marks the day Willie Mae Thornton, aka Big Mama Thornton was born — a woman whose defiance of stereotypes changed music as we know it.

Thornton is known for the songs “Hound Dog,” which was written specifically for Thornton by Mike Stoller and Jerry Lieber, and for “Ball and Chain.” While the songs were popularized by white artists Elvis Presley and Janis Joplin, the story of Thornton, her influence on contemporary music, and the credit she was due for her contributions are often left untold.

During her 44-year career, Thornton was nominated for the Blues Music Awards six times, wrote and recorded more than 20 songs, and in 1984, the year of her death, she was inducted into to the Blues Hall of Fame. In 2020, she was also inducted into the Alabama Music Hall of Fame.

In honor of Thornton’s birthday, Colorado-based blues musicians who shared the stage with Thornton and follow in her footsteps gathered to play her music and reminisce on her impact.

“Big Mama Thornton paved the way for people like me, you know, to do what I do today and to do it the way I do it and to do it with the feeling that I do it with,” said Erica Brown, a Denver-based blues musician who tells Thornton’s story by covering her music and sharing the story of her life.

Erica Brown has taken on the mission to honor Thornton’s legacy and said it woke her up in the dead of night.

After touring with Big Head Todd and the Monsters in a tribute to Willie Dixon, Brown was determined to pay homage to another blues artist. One night, she woke up with a start, hearing an inner voice telling her she was meant to honor Big Mama Thornton.

“So I laid back down and went back to bed. I went back to sleep. When I woke up the next morning, the thought was still there and it was so strong,” she recalled, “As my mother used to say, I followed my first mind.”

Brown immediately got to work studying Thornton’s legacy, and right off the bat learned their first commonality: the name Willie Mae.

“Her legal name was Willie Mae Thornton. My legal name is Willie Mae Brown,” Brown said. She decided to call her tribute album with collaborator Julian Peterson “Willie Mae Sings Willie Mae."

“I think she’d like that,” Brown said, beaming.

Erica Brown sings her arrangements of Big Mama Thornton’s works with collaborator Julian Peterson.

Photo: Elle Naef, Rocky Mountain PBS

The more Brown learned Thornton’s story, the more connected she became.

Big Mama Thornton was born Willie Mae Thornton near Montgomery, Alabama in 1926.The daughter of a minister, Thornton’s earliest exposure to music was to southern gospel choirs. She learned vocals watching her mother Mattie singing in the church choir, and taught herself instruments such as the harmonica and drums by listening to her brother.

“She would go and sit in front of that bus station on a little concrete platform and play harmonica and sing, and she knew that's what she wanted to do,” said Brown.

According to Oxford American, Thornton ran away at age 13 after her mother died from tuberculosis. An artist named Diamond Teeth Mary took her under her wing after hearing Thornton sing, and soon afterwards she began touring with Sammy Greene’s Hot Harlem Revue.

In time, Willie Mae became known as Big Mama — not just because of her large stature, but for her commanding stage presence. From her bellowing voice that needed no microphone to her ability to jam on any instrument set before her, Thornton was in a class of her own.

“She was a pioneer,” said Sammy Mayfield, a Colorado blues guitarist. “She's the one who created the blues, you might as well say.”

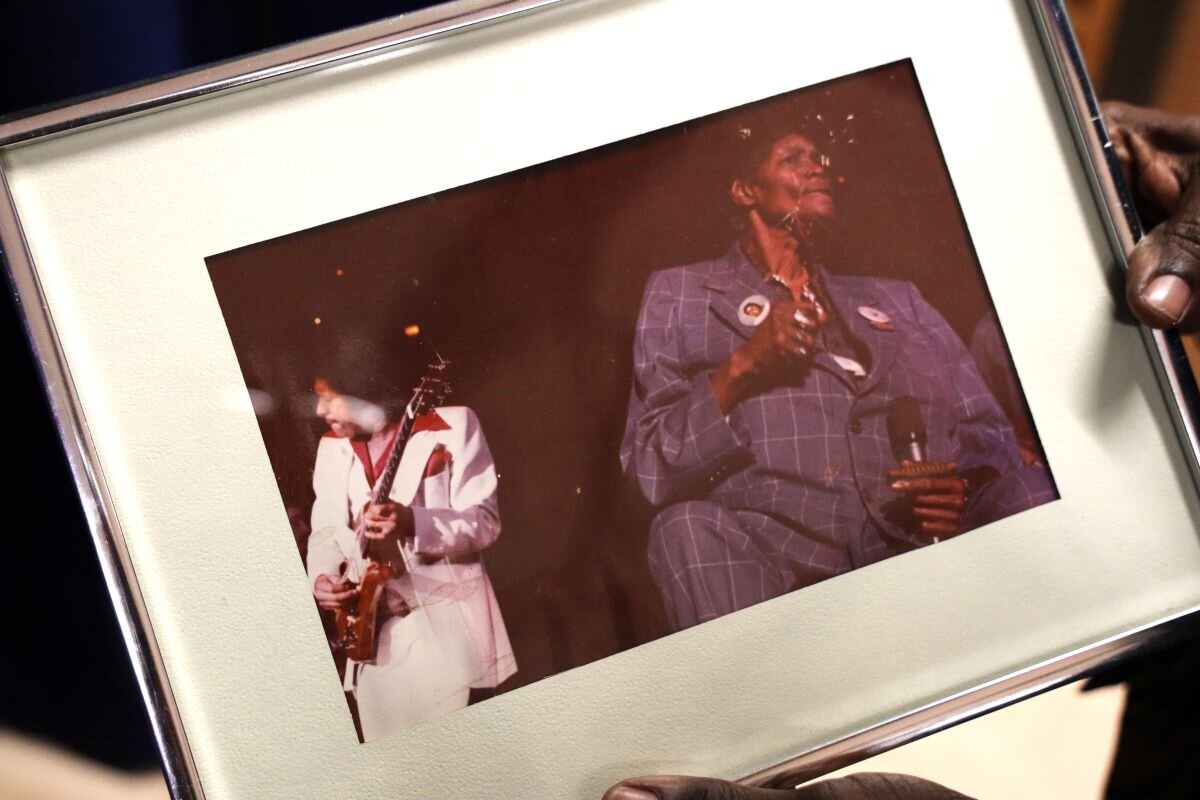

Mayfield would know. He once played guitar in Big Mama’s band opening up for B.B. King at McNichols Arena in Denver before it closed.

Sammy Mayfield shows a framed image of he and Big Mama Thornton performing at McNichols Arena.

Photo: Elle Naef, Rocky Mountain PBS

According to Mayfield, the joy of playing with Thornton went beyond the thrill of a packed arena. His experience making music with her changed his perspective of the genre as a whole. Mayfield, who was raised on the blues, was fluent in the musical elements. “It’s my heart, it’s my soul, it’s what I do.”

But Thornton, he said, helped deepen the meaning of the genre.

“I enjoyed the experience because she was just such a warm person,” Mayfield said, “She had so much feeling. And that's what I took away from that show. I learned how to calculate that feeling of the blues.”

Dan Treanor, a Colorado-based blues and rock musician who also toured the world, was, like many youth during the time, somewhat new to the blues in the 60s. He had gained a deep respect for it by 1971, when he played with Big Mama Thornton in Minneapolis.

“The thing that always touched me about the blues was how real it is. How much it reflects life and emotion,” he said.

Dan Treanor, blues musician and harpsichord player, plays a Big Mama Thornton cover with Brown and Peterson.

Photo: Elle Naef, Rocky Mountain PBS

Treanor remembered every detail of the show — like Big Mama calling the band into her dressing room wearing dungarees, a hair wrap, and a button-up shirt, with a half-empty bottle of vodka beside her. She had the band play a bit, nodded in approval, then sent them away.

Once they were on stage, Treanor recalled, Thornton said “Boys, play me a shuffle!” She then worked her way around the stage, jamming on each instrument.

“When you're in the presence of somebody that has that kind of power,” said Treanor, “ [you] try to absorb a little bit of their energy.”

Thornton's confidence, Treanor said, was especially important considering the blues genre was male-dominated.

There are varying accounts regarding Thornton’s sexuality, but Brown said Thornton’s presentation alone broke gender stereotypes.

“She was what one writer called a gender transgressor,” Brown said. “She did not let the world tell her how to dress, who to be, how to sing, or how to live her life.”

According to Brown and Treanor, Big Mama’s musical influence can be heard in contemporary music.

“If you listened to you listen to Top 40 music today, you hear the blues in every aspect of it. Rap and hip-hop, that's just moderate version of the blues — the grooves and the storytelling,” said Treanor.

Brown emphasized how Thornton’s presence alone changed the game for performers.

“She paved the way for women like Janelle Monae to say, ‘I don't have to be scared or ashamed or anything about who I am and how I practice my art,” Brown said. “And because we have that template, especially Black female artists, we can be whoever we want to be, and the rest of the world will fall right in line.”

Big Mama Thornton died from a heart attack in 1984. Despite Thornton’s notable influence, she was buried in an indigent grave with two other people. Brown was appalled to learn this in her research.

“I was outraged. I was like, ‘how does that happen?’ So I researched deeper, and she died broke,” said Brown. “She didn't even remotely come close to the recognition or the financial remuneration that she should have received, considering that she's one of the foremothers of American music.”

Treanor gave just one example of how this came to be. He said that despite Thornton writing “Ball and Chain,” a song that has become a classic, the record company retained all the rights.

“So when it broke, she didn't get a penny for it,” he said. “And that was that was pretty typical of what was going on with with the blues musicians back in those days.”

Brown’s disappointment with Thornton’s treatment fueled the next step in her tribute to the artist: giving her a proper memorial. Now, Brown plans to work with the family to determine how to best memorialize Thornton.

“She lived life on her own terms, and we are all so much better for her having walked this earth.”

Elle Naef is a multimedia producer for Rocky Mountain PBS. ellenaef@rmpbs.org

Peter Vo is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS. petervo@rmpbs.org