Wildfires in Colorado are growing more unpredictable. Officials have ignored the warnings.

This story was originally published by ProPublica and Colorado News Collaborative

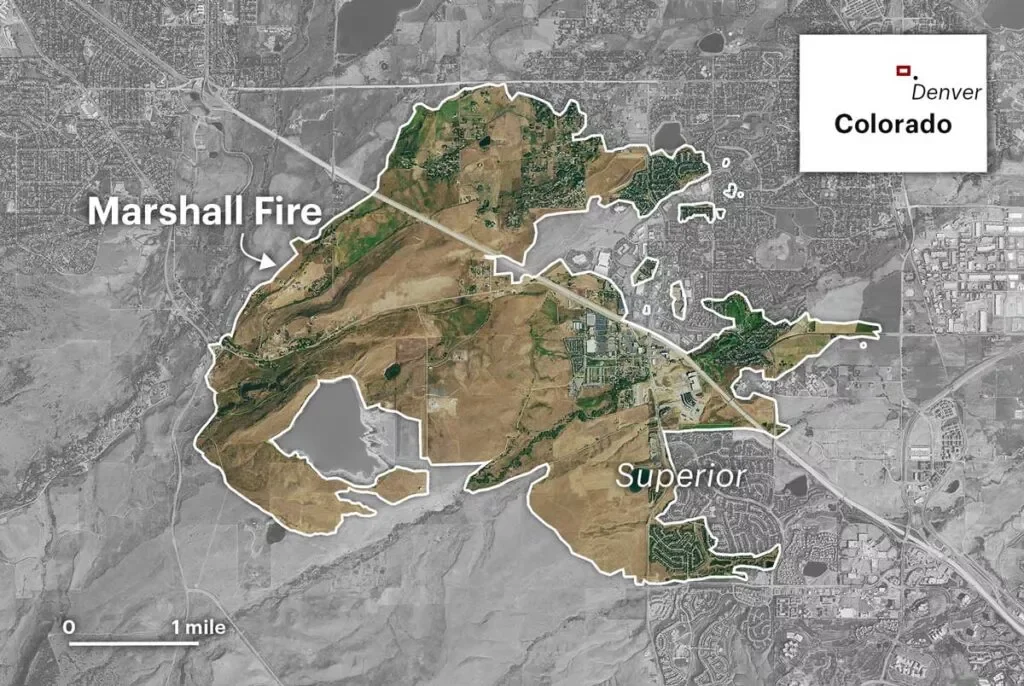

Sheriff’s deputies driving 45 mph couldn’t outpace the flames. Dense smoke, swirling dust and flying plywood obscured the firestorm’s growth and direction, delaying evacuations.

Within minutes, landscaped islands in a Costco parking lot in Superior, Colorado, caught fire as structures became the inferno’s primary fuel. It consumed the Element Hotel, as well as part of a Tesla service center, a Target and the entire Sagamore neighborhood. Across a six-lane freeway, in the town of Louisville, flames rocketed through parks and climbed wooden fences, setting homes ablaze. They spread from one residence to the next in a mere eight minutes, reaching temperatures as high as 1,650 degrees.

On Dec. 30, 2021, more than 35,000 people in Superior and Louisville, as well as unincorporated Boulder County, fled the fire — some so quickly they left barefoot and without their pets. Firefighters abandoned miles of hose in neighborhood driveways to escape.

The Marshall Fire, the most destructive in Colorado history, killed two people and incinerated 1,084 residences and seven businesses within hours. Financial losses are expected to top $2 billion.

The blaze showed that Colorado and much of the West face a fire threat unlike anything they have seen. No longer is the danger limited to homes adjacent to forests. Urban areas are threatened, too.

Yet despite previous warnings of this new threat, ProPublica found Colorado’s response hasn’t kept pace. Legislative efforts to make homes safer by requiring fire-resistant materials in their construction have been repeatedly stymied by developers and municipalities, while taxpayers shoulder the growing cost to put out the fires and rebuild in their aftermath.

Many residents are unaware they are now at risk because federal and state wildfire forecasts and maps also haven’t kept pace with the growing danger to their communities. Indeed, some wildland fire forecasts model urban areas as “non-burnable,” even though the Marshall Fire proved otherwise.

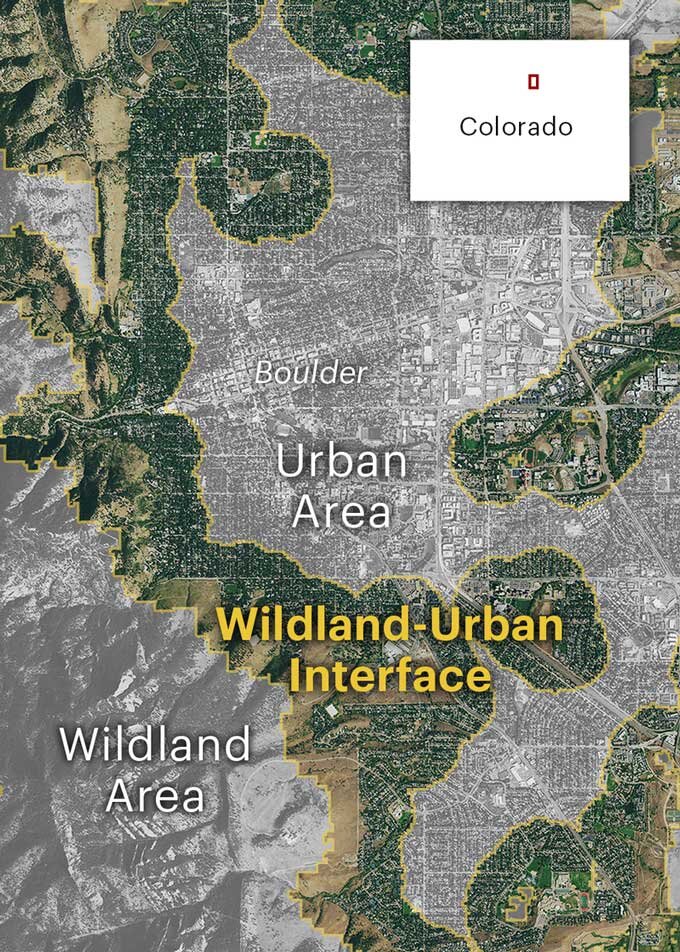

The disaster put an exclamation point on what scientists, planners and federal officials warned for years: Communities outside the traditional wildland-urban interface, or WUI, are now vulnerable as a changing climate, overgrown forests and explosive development across the West fuel ever-unpredictable fire behavior. Fire experts define the WUI, pronounced woo-ee, as areas where plants such as trees, shrubs and grasses are near, or mixed with, homes, power lines, businesses and other human development.

They now agree that instead of a threat confined to the WUI, the entire state, including areas far from forests, may be at risk of a conflagration.

“The Marshall Fire was a horrible, tragic event that served as a wake-up call for the rest of our state,” said state Rep. Lisa Cutter, a Democrat who represents mountain and foothill areas. “I don’t think we realized how much wildfire could impact communities that aren’t deep in the forest — it’s not something any of us are immune to.”

Unheeded Warnings

An early warning of the growing danger to suburban communities arrived in 2001. That year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and other federal agencies identified scores of Colorado municipalities adjacent to public lands as being at high risk of a wildland blaze-turned-urban conflagration. Some of these areas burned in the Marshall Fire.

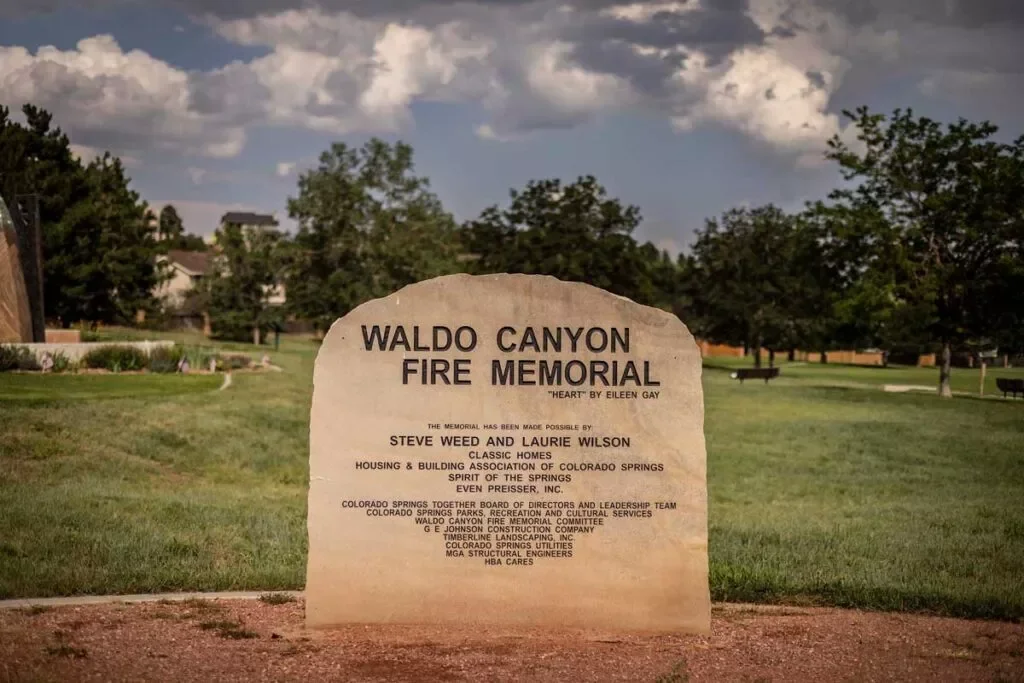

A decade later, in 2012, another warning came, as an unprecedented weather-driven inferno, the Waldo Canyon Fire, destroyed several Colorado Springs neighborhoods.

Afterward, fire experts urged state lawmakers to adopt a model building code that communities in high-risk areas could enact. Such codes have been scientifically proven to reduce risk for residents and rescuers and to increase the odds structures will withstand a blaze by requiring fire-resistant materials on siding, roofs, decks and fences, along with mesh-covered vents that prevent embers from entering.

But lawmakers bowed to pressure from building and real estate lobbyists as well as municipal officials who demanded local control over private property.

Meanwhile, the number of new homes built in Colorado’s WUI — as defined by researchers several years ago — more than doubled between 1990 and 2020. And nationwide, the WUI is growing by 2 million acres a year. Homes in 70,000 communities worth $1.3 trillion are now within the path of a firestorm, according to a June report from the U.S. Fire Administration that featured photos of the Marshall Fire’s destruction.

In the months that followed the Marshall Fire, there were again calls to consider a statewide building code. A last-minute amendment to a fire mitigation bill in May would have created a board to develop statewide building rules, but it was pulled after builders, real estate agents, municipalities and others opposed it.

It wasn’t the first time the state’s powerful building industry asserted its influence over policy. Whenever a wildfire bill comes to the state legislature, well-heeled lobbyists routinely represent the industry, records kept by the Colorado secretary of state show. The state’s culture of local control and the construction industry’s $25 billion annual contribution to the economy hampered lawmakers’ ability to find middle ground on a minimum statewide building code.

ProPublica’s review of legislation introduced from 2014 to 2022 found only 15 out of 77 wildfire-related bills focused primarily on helping homeowners mitigate their risk from fires. Most of the 15 proposals offered incentives to homeowners and communities through income tax deductions or grants — some of which required municipalities to raise matching funds — to clear vegetation around structures.

None called for mandatory building requirements in wildfire-prone areas, even as 15 of the 20 largest wildfires in state history have occurred since 2012.

The lack of uniform regulations has cost the Centennial State millions in federal grant money: The Federal Emergency Management Agency denied the state grants from the agency’s resilient infrastructure funds, which from fiscal 2020 to 2022 totaled $101 million.

Colorado remains one of only eight states without a minimum construction standard for homes.

Municipalities Weigh Prevention and Its Cost

Developers have also influenced municipalities’ recent decisions, as homes decimated by the Marshall Fire are rebuilt in Boulder County, and the cities of Superior and Louisville located within it. The debate has reflected difficult tradeoffs between the cost of making homes more fire-resistant — particularly in an era of high inflation and unpredictable supply chains — and residents’ tolerance for risk.

Lawmakers in Louisville, where 550 homes and businesses burned, voted to remove a fire sprinkler requirement for homes, citing cost, despite evidence such systems reduce the risk of dying in a home fire by 80%. The City Council also voted to allow residents to choose whether to follow new energy efficiency requirements estimated to add $5,000 to $100,000 to the cost of a new home.

By contrast, in unincorporated Boulder County, which lost 157 homes to the Marshall Fire, commissioners in June voted to require fire-resistant materials on all new and renovated homes. Before the inferno, the eastern grasslands were exempt. (Mountain residents, who since 1989 have been required to follow mitigation practices, have seen the effectiveness of such codes: Eight out of 10 of their homes survived the Fourmile Canyon Fire in 2010.)

In Superior, which lost 378 structures, the Board of Trustees voted down a proposed citywide WUI building code in May. After residents of the leveled Sagamore neighborhood requested they revisit their decision, trustees reconsidered in July.

The financial pressures facing Superior officials and their constituents were evident as they considered whether to require fire-resistant materials solely for homes destroyed by the Marshall Fire or for the entire city.

“This is all a huge cost we cannot bear,” said Robert Lousberg, a resident who wants to rebuild several homes. “I understood this is a once-in-a-lifetime fire.”

Some neighbors disagreed.

“Sagamore burned down in less than an hour — one of my neighbors ended up in the hospital after trying to escape the fire on foot — that’s the main reason we need these codes, to slow the spread of fire,” Dan Cole said. “We have an opportunity to build a more fire-resistant neighborhood right now, and it would be foolish and short sighted not to take it.”

Builders estimated that costs for tempered-glass windows, fire-resistant siding and other materials could reach $5,500 to $30,000 per home. Procuring the materials and labor to install them could delay rebuilding.

Like residents, town trustees were divided about whether the cost outweighed safety benefits to residents and first responders should there be another conflagration.

“To me, it’s unconscionable to have people rebuilding in an unsafe manner,” said Trustee Laura Skladzinski, who did not seek reelection last month. “I would rather have residents pay $20,000 now. If they cannot afford it, how are they going to be able to afford it when their house burns down?”

Some noted that most residents didn’t have enough insurance to cover the cost of rebuilding their homes.

Trustee Neal Shah said the city should have adopted tougher codes after the 2012 Waldo Canyon Fire in Colorado Springs, which prompted calls for a voluntary statewide building code that communities could institute requiring fire-resistant materials in homes.

“I fundamentally believe in WUI standards,” Shah said, “what I can’t solve is the math.”

The body voted 5-1 to institute the code, then added an opt-out clause for those rebuilding their residences.

Colorado Springs Fire Foreshadowed the Risks

A decade before the Marshall Fire, a blaze was burning in the mountains above Colorado Springs on a 101-degree June day. That afternoon a thunderstorm caused a sudden shift in the wind, pushing a wall of burning debris out of the Rocky Mountain foothills into the state’s second-largest city.

Firefighters fled the 750-foot-high fire front — as tall as a 53-floor building — as it chewed through pine, pinyon and juniper dried by a record-hot spring. Sixty-mile-per-hour gusts peeled back the door on a fire truck. Fist-sized embers rained down on the city’s Mountain Shadows community. The fire incinerated 79 homes per hour, or 1.3 per minute, over 5 ½ hours,

In the aftermath of the Waldo Canyon Fire, which destroyed 347 homes and killed two people, Colorado Springs drew lessons from which residences had survived and capitalized on fresh memories of burned neighborhoods to institute tougher building requirements.

Standing recently in the shade of a still-scorched tree behind her home, Patty Johnson described how her house was relatively unscathed, even as eight of her neighbors lost their residences. She credited ignition-resistant materials, including stucco walls, siding, a composite deck and a concrete tile roof. Drought-resistant landscaping also helped. Her family sold the home in September to move into a smaller place in the city.

After-action reports found neighbors’ work clearing vegetation around homes helped firefighters save 82% of residences in the 28-square-mile burn area.

FEMA estimated that minimal expenditures to protect Colorado Springs neighborhoods had paid off. In Cedar Heights, $300,000 in mitigation had prevented about $77 million in losses.

“The Waldo Canyon Fire was shocking, but it could have been so much worse if the city of Colorado Springs had not spent decades getting ready,” said Molly Mowery, co-founder of the Community Wildfire Planning Center.

Even so, the fire reached 2,000 degrees and moved so fast it incinerated some homes with fire-resistant material and fire-proof safes inside.

Nevertheless, the city followed a 30-year pattern and took its lessons to heart to institute additional building requirements to fortify homes in wildfire-prone areas. Timing was everything, Mowery’s nonprofit concluded in a recently released analysis.

The city had done the same in 2002. With smoke still in the air following the Hayman Fire — which started about 35 miles northwest of the city and destroyed 600 structures — a coalition of fire officials, homeowners’ associations and local builders and roofing contractors devised rules that banned wood roofs on all new homes and repairs greater than 25% of the total roof area.

Similarly, after the Waldo Canyon Fire, as heavy machinery cleared charred neighborhoods, the city updated its code to increase the distance trees had to be from homes and require fire protection systems, ignition-resistant siding and decks, and double-paned windows for all new or reconstructed homes in

Fire officials used spatial technology to hone the city’s definition of the WUI. The tool identified a 32,655-acre area — one of the largest high-risk regions in the United States. The city recruited homeowners to educate neighbors in the threatened area about fire-resistant practices.

Peer pressure worked, said Ashley Whitworth, wildfire mitigation program administrator at the Colorado Springs Fire Department. If a homeowner’s property is flagged red on the city’s online risk assessment map (denoting it needs work), neighbors reach out to learn why they haven’t completed mitigation.

Colorado Springs’ voters overwhelmingly approved the allocation of $20 million in city funds toward incentives to gird wildfire-prone properties.

Days after the vote in November 2021, the Marshall Fire unfolded 90 miles to the north across communities with little history of wildfire mitigation.

Scientists, some of whom lived in Boulder County and were evacuated, proclaimed it a “climate fire.” They cited the extreme weather that preceded it: Abnormally high levels of snow and rain in spring and summer had nurtured abundant 4-foot grasses that baked to a crisp during a historically dry fall. Chinook winds blasted the region for an unusual nine-hour period and propelled the firestorm. And even though there’s growing understanding that fire season is now year-round, no one believed a December blaze could ravage entire cities.

While it began as a wildfire in grassland, once it reached nearby communities it transformed into an urban conflagration — the type of fire that destroyed Chicago in 1871 and San Francisco in 1906 and that until the early 20th century consumed more property than any other type of natural disaster.

“Was this a wildland fire or an urban fire?” Sterling Folden, deputy chief of the Mountain View Fire Protection District, asked during a July legislative committee meeting. “I had five fire trucks in the entire downtown of Superior — I had 20 blocks on fire — I usually have that many for one house on fire.”

Whitworth, of the Colorado Springs Fire Department, said there were more lessons to learn about the threat of wildfire.

“The Marshall Fire was a really big hit for people here because it happened in December and it happened just like that,” Whitworth said. “Everyone said to me, ‘It could happen here,’ and I said, ‘You’re absolutely right.’”

Is the Entire State Now Vulnerable to Wildfire?

With the 2023 legislative session days away, fire chiefs, county commissioners, scientists and planners are once again calling on Colorado lawmakers to institute statewide rules that mandate fire-resistant materials in high-risk areas.

Cutter, who will be sworn in as a state senator in January, is developing a bill that would require the state to create a WUI code board to write minimum fire-resistant building requirements. It’s patterned in part after the amendment that failed at the Capitol this spring.

Such laws save lives, said Mike Morgan, director of the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control. The 36-year fire service veteran cited studies from the nonprofit Fire Safety Research Institute and the federal National Institute of Standards and Technology showing that building codes work.

“Firefighters take extraordinary risk to protect lives and property,” he added. “If we start building communities and structures out of materials more resistive to fire, we are upping our odds of success — we’ve got to do something different and do it better.”

The insurance industry is also warning that if Colorado lawmakers and communities don’t reinforce homes against wildfire, mounting claims from blazes could put premiums out of reach for many. The industry supports a statewide building code.

“Unlike other disasters, wildfire is one of those risks there is much we can do from a mitigation standpoint to put odds at least in favor of that home surviving,” said Carole Walker, executive director of the Rocky Mountain Insurance Information Association.

“We’ve got to get it done,” she added. “Colorado right now is at … a tipping point with concerns about keeping insurance here and keeping insurance available.”

But such rules won’t be adopted without a compromise among local control advocates, builders and fire officials.

Construction industry representatives who met with Cutter and Morgan recently said builders are wary of one-size-fits-all requirements imposed by the state. Together with the insurance industry and municipal governments, they have met the past few months seeking to influence the bill’s language.

“It’s important to make sure we match codes with risk,” said Ted Leighty, chief executive of the Colorado Association of Home Builders. His members “are not opposed to talking about what a code board might look like — if we were to adopt a model code that local governments could adopt to match their communities’ needs.”

The idea for such a board emerged after the Colorado Fire Commission received a letter from Gov. Jared Polis in July 2021.

The first-term Democrat, who was reelected in November, sent the missive following conflagrations in 2020 that exhibited unimaginable fire behavior: The 193,812-acre East Troublesome Fire traveled 25 miles overnight and incinerated 366 homes; and the 208,913-acre Cameron Peak Fire, which torched 461 structures, burned for four months despite firefighters’ efforts.

Polis wrote that legislators in 2021 had failed to “address a critical piece of the wildfire puzzle in Colorado: land use planning, development and building resiliency in the wildland-urban interface.”

Instead, lawmakers focused on fire response, restoration of burned lands and voluntary mitigation by communities.

In answer to Polis’ missive, a little-known subcommittee, which included state, county and city fire officials, met between August 2021 and April. The 51-member group agreed it’s time to rethink which communities are prone to wildfire, offering a new definition of the WUI: The group concluded “almost the entire state of Colorado falls within the WUI,” according to minutes from a Feb. 10 meeting, “which could make a strong argument for adopting a minimum code.”

Fire officials also countered the long-held belief that communities favor local control over building requirements. They pointed to a 2019 law that established a minimum energy code that local jurisdictions must adopt when they update local building codes. About 86% of the state’s 5 million residents now live in a community that mandates such measures.

“There is minimal evidence that people voluntarily regulate themselves,” committee members concluded, according to minutes of their Feb. 28 meeting.

Rebuilding Like Before

A report on the Marshall Fire released in October by the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control noted how wooden fences abuting grasslands had accelerated the blaze’s spread, leading flames from the grass directly to homes. Firefighters also described fence pickets flying past at 80 mph and landing to start new fires.

This month, as homes were being rebuilt on Cherrywood Lane in Louisville, in one of the hardest-hit neighborhoods, evidence remained of first responders’ frantic efforts to cut down fences to prevent them from spreading flames to neighboring homes.

New homes are going up across the 9-square-mile burn zone. A recent drive through the area revealed many are being rebuilt with the same kinds of fences. With no building code dictating that the fences be made of fire-resistant materials, homeowners are using flammable materials that have been standard in the past, unaware it will again put them at risk in the next blaze.

Wooden fences such as these touch homes and grasslands in communities up and down the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains.

Rebuilding without ignition-resistant barriers leaves the homes vulnerable to the next climate-driven wildfire, said Morgan, the state fire chief.

This month, with snow on the ground and temperatures in the 40s, another blaze ignited not far from where the Marshall Fire burned. Thirty-five-mile-per-hour winds spread the flames and forced evacuations before the threat subsided.

“I’ve heard people say the Marshall Fire was just a fluke,” he said. “I would disagree — there are literally thousands of communities along the Front Range of the Rockies from Canada to New Mexico subject to these Chinook winds multiple times a year, and when the conditions are right this can happen.”