Art world mystery: How a famous painting made its way to a Denver office park

share

DENVER — In an ordinary office building in an ordinary office park off an ordinary road is something very unordinary: a painting by one of the greatest Spanish masters of the 17th century — lost for decades and newly discovered — and likely worth millions.

For the past 40 years, the Western Center for the Conservation of Fine Arts (WCCFA) has been treating some of the most well-known paintings from across the centuries, from Jackson Pollocks to Remingtons to Georgia O Keeffes.

Two years ago, a client brought the center what was believed to be Jusepe de Ribera’s “Deposition of Christ” painting to treat before putting it up for auction. The painting was long forgotten about and in terrible condition. Emily MacDonald-Korth, the owner and chief conservator-scientist of the WCCFA, was tasked with analyzing the painting to help authenticate it, and returning it to its former glory.

“We couldn't even give an accurate proposal for how long the treatment would take because of the severity of the condition of this painting,” she said.

Despite the volume of high-valued art on the premises, MacDonald-Korth doesn’t work in a secretive location surrounded by armed guards.

“In 40 years of practice, we never once had a problem,” she said of would-be art thieves.

“We have security alarms that are constantly monitored, we have fire detection and fire extinguishers, and we have wonderful insurance.”

Conservation is the practice of cleaning, repairing and maintaining art to preserve the art’s cultural heritage. Working in the field requires an understanding of fine arts, science and history, and most working conservators have specialized master’s degrees in the discipline.

“It's like surgery, but no one's going to die if you make a mistake,” MacDonald-Korth said. "It’s that level of intensity.”

WCCFA is one of the few conservation labs in the west — a region teeming with western paintings, wealthy collectors, and museums and galleries — but lacking in skilled conservators compared to the east and west coasts of the United States.

The items that come in to WCCFA range in their level of disrepair. Some have been destroyed by calamities such as fires and floods, others have fallen victim to accidental coffee or water spills, and some have simply accrued dust speckles over time.

Historically, many paintings were restored in ways that painted over original artwork or tampered with important aspects of the original piece. As centuries of restorations have accrued, some paintings have lost much of their original identity and attributes — a challenge MacDonald-Korth and her team must regularly contend with.

“A lot of times, the majority of the work we do is reversing other people's bad restoration,” said MacDonald-Korth.

Lost for centuries — and recently found

This possible Ribera “Deposition of Christ” painting is one of the most exciting projects WCCFA has ever worked on.

Ribera (1591 – 1652) was considered one of the great Spanish masters of the 17th century, alongside Diego Velasquez, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo and Francisco de Zurbarán. His paintings are on display at the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the National Gallery in London and the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

But, up until now, this “Deposition of Christ” painting was lost and forgotten about.

Jusepe de Ribera’s “Deposition of Christ,” depicts the moment Jesus’ body was taken off the cross and brought into a cave to be entombed. He is surrounded by some of the most important people to him, including his mother — the Virgin Mary — and Mary Magdalene. It’s one of the rare paintings Ribera made that includes Jesus Christ himself.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS.

Perhaps the biggest surprise about the painting — besides the fact that it still exists — is who brought it in: Jake Haas, a Lakewood dumpster diver-turned door-to-door salesman of Denver Broncos merchandise-turned antiques and watches dealer.

“This almost never happens. I have found very few authentic, extremely valuable paintings,” said MacDonald-Korth. “If this painting ends up selling through one of the giant auction houses or a museum or something, we need to write a book because it's like a guy who sells secondhand Rolexes found a frickin’ old masterwork. It's like the story everyone wants to hear.”

Haas spotted the painting in 2018 at Corbett’s Auction House in Littleton and was enamored by it but didn’t have the $20,000 he needed to make the starting bid for both the Ribera and another 17th century painting the auction house had paired with it (that one was a painting by Giovanni Battista Benaschi).

“When I saw those paintings, I thought about them every single day,” Haas said.

Over several years, while the paintings went unsold, Haas made a habit of frequenting the auction house on weekends trying to bargain the price down.

Eventually, in 2021, he succeeded and got a deal: He paid $5,000 for the two pieces — an amount many of his friends scoffed at.

Haas believed the painting was an actual Ribera and worth far more than he paid for it, so he enlisted the help of Timothy J. Standring, curator emeritus at the Denver Art Museum to do historical research, and WCCFA to conduct scientific analysis and treatment.

Haas didn’t have enough money to pay MacDonald-Korth to start the work, so he offered her silver coins, which she accepted.

“When is anybody ever going to pay me in silver coins again?” she laughed.

A few months ago, after doing UV and infrared photography, MacDonald-Korth spotted a Ribera signature, date, and the word “Lo Spagnoletto” or “Little Spaniard” — a nickname Ribera inherited after he left his birthplace of Spain for Italy.

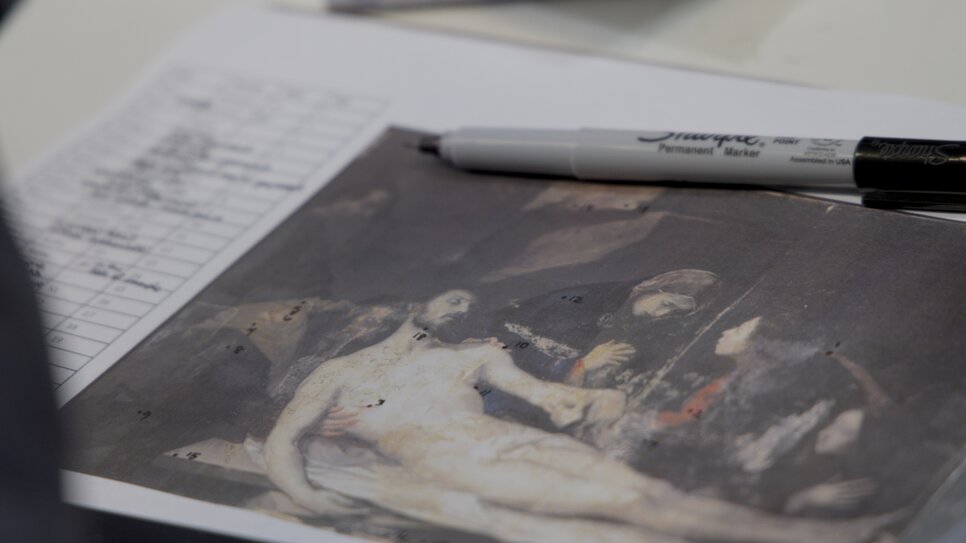

MacDonald-Korth and her team are currently conducting pigment analysis of the paint using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) to determine if the pigments in the painting were around during Ribera’s time. So far, the results have been "excellent."

MacDonald-Korth and her team take notes while using XRF to analyze the painting’s pigments.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

The team also collected microscopic samples of the paint to verify the results of the XRF.

“Whenever possible, I use two techniques that come to the same conclusion before I am convinced,” said. MacDonald-Korth.

The team will also be doing extensive treatment on the painting, which came in with several prior restorations that destroyed many of the original paint layers. WCCFA will be employing two in-painters over the next few months to simultaneously work together to replace all the original paint that is missing.

“A lot of times people are like, ‘Oh God, there's so much restoration. It's terrible,’” said MacDonald-Korth. “I see that as a good thing. You don't spend that much money and time on restoration unless you think your painting's important.”

For the painting’s provenance — or documented history of the painting, which is critical when buying and selling high-valued works — Haas enlisted help from the foremost Ribera authority and scholar, an Italian in his 80s named Nicola Spinosa.

Spinosa is notoriously difficult to get in touch with, and it took two years for Haas to get a reply. It only came after he sent over the infrared and UV photos taken from MacDonald-Korth.

Spinosa’s known history of the painting appears to track. The painting of note, which appears to be this one, was in several hands in Italy, including by the princess of Piedmont in Naples and the Medici di Ottajano, according to Spinosa’s email to Haas. It left Naples for the United States in 1908 at the request of an American Catholic Bishop.

More recent provenance shows the painting went to a bishop in Denver and made its way to the Park Hill neighborhood. A pastor named Andrew Lee Bowman eventually bought a church and attached school in the neighborhood between 1972 and 1974. Several paintings, including the Ribera were displayed inside the buildings.

Bowman died in 2005 and his estate sold the Ribera to Corbett’s in 2017, where Haas purchased it.

Standring and Spinosa independently determined similar provenance for the painting, but neither of them have authored a formal opinion yet. Spinosa wants to see the painting after it’s been treated to give his final validation.

A close-up of the Ribera painting shows the extent of original paint that has been lost.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

Remarkably, spotting the work of an old Spanish Master wasn’t Haas’s first brush with good luck and good timing.

In 2018, while driving in Denver, he spotted what he thought were antique maps on the side of the road next to a trash can. He pulled over and found more than 500 blueprints of the World Trade Center.

They were owned by one of the architects of the World Trade Center, Joseph Solomon, who took them to Denver as a keepsake of his career after he left New York. His daughter threw them out while cleaning out her father’s belongings following his death.

Haas sold them to a pawn shop dealer for $20,000 — more than he made in a single year — who then sold them for $250,000. The story made national headlines.

“I kind of missed the boat on that one,” Haas said, and he hopes to not make the same mistake with the Ribera painting.

So far, Haas has spent a total of $200,000 on the painting’s provenance, analysis and treatment – with most of that money going to WCFAA and Standring. To pay for it all, he tapped out his savings of $100,000 and sold his silver.

“I put every dollar I ever had into that painting,” Haas said. “Hopefully this painting will buy me a lot more silver. That’s what I hope.”

MacDonald-Korth and her team plan to complete their work by October 1, so Haas can show the work to Christie’s Auction House, which has agreed to fly to Denver and appraise “Deposition of Christ” in person once WCCFA’s conservation work is complete.

“He trusted his eye, and trusted his gut and he was right. It's incredible,” said MacDonald-Korth.

The professionalization of an industry

Art conservators, like MacDonald-Korth, have significantly more training, education and an understanding of science, compared to art restorers.

There are only a handful of three-to-four-year master’s degree programs in the U.S. specializing in art conservation. The most well-known are the Winterthur program at the University of Delaware, New York University and Buffalo State. All three programs take in less than 10 students per year, offer free tuition, and require extensive conservation experience and related coursework prior to admission.

MacDonald-Korth, who graduated from Winterthur in 2011, said she didn’t get in the first time she interviewed there, and applied to NYU’s program so many times over the span of several years that they told her she could never apply to a graduate program at the university again.

MacDonald-Korth spreads her time between WCCFA’s labs in Denver and Miami.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

She interned with WCCFA in 2009 during graduate school and bought the company from its previous owner in 2023. In addition to opening a lab in Miami and adding forensic analysis to the team’s workload, she is working on establishing a formal internship program with the University of Denver.

“All the conservators that work at our company only got to be conservators because other people advocated for them,” she said.

MacDonald Korth said to excel in the field, one doesn’t need to be an artist, but must be knowledgeable about art materials.

“The most important thing is to understand how paintings are made, which then can tell us why they deteriorated the way that they did,” she said. “If you don't understand what paint is and what canvas is and what varnish is, you can't understand why it deteriorates.”

The majority of the paintings WCCFA treats are from private collectors, including many who divide their time between Aspen and the east coast. Because of the high value of some of the paintings, MacDonald-Korth remains cognizant of privacy issues, and only speaks about, or shows paintings, with prior approval from her clients.

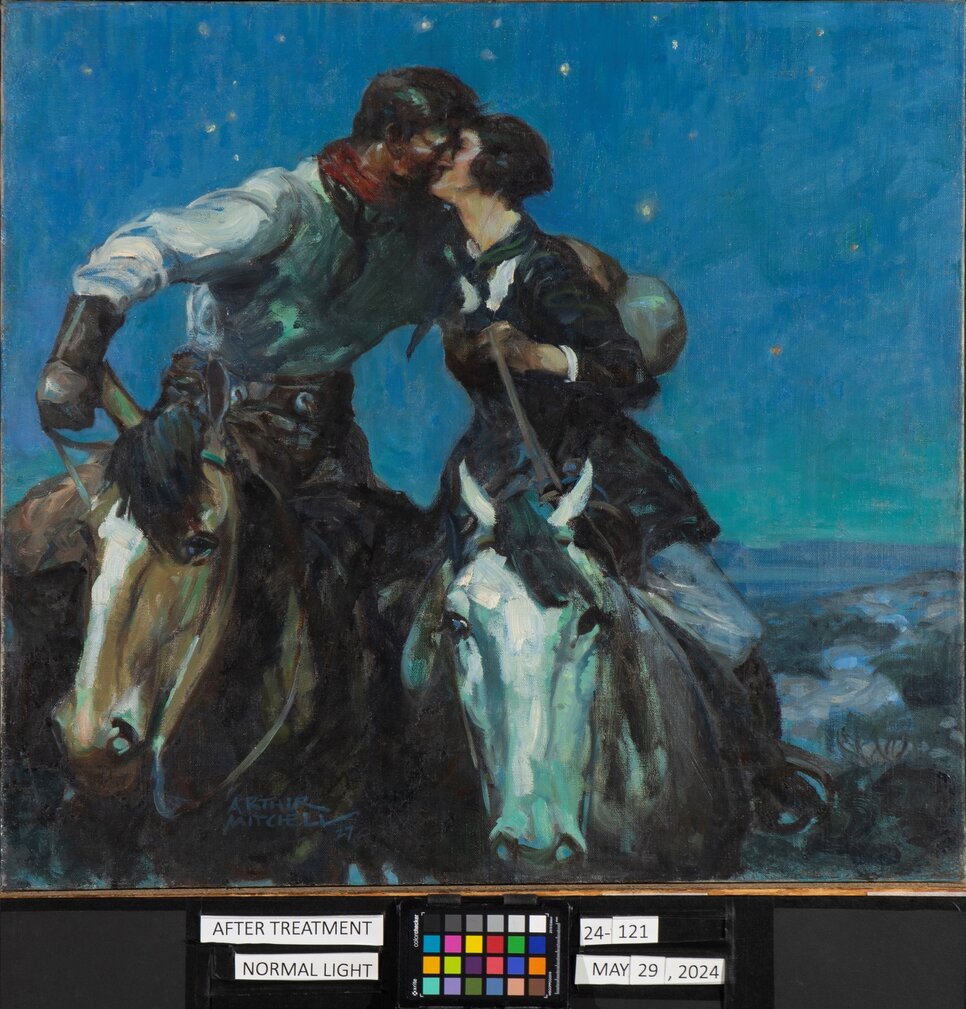

WCCFA also treats paintings from museums and cultural institutions throughout the West. These include the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, which has the largest public collection of Carl Rungius, a preeminent German-born painter known for his paintings of American wildlife. The center also works with Brigham Young University and the AR Mitchell Museum of Western Art in Trinidad, Colorado, where many paintings were recently damaged by a nearby fire.

The Western Center for the Conservation of Fine Arts (WCCFA) treated A.R. Mitchell’s 1927 “The Goodnight Kiss” after a fire near the A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art in Trinidad caused smoke damage to the collection.

Photo courtesy the Western Center for the Conservation of Fine Arts (WCCFA)

Photo courtesy the Western Center for the Conservation of Fine Arts (WCCFA)

MacDonald-Korth and her team also treat murals, including those at Denver International Airport.

“The airport murals have a rough life with millions of people passing by them,” she said. “They just treat it like a wall, so we’re there to fix it.”

Aside from their work treating paintings and murals, the team now also does forensic analyses of paintings, like they did on the Ribera, using infrared and ultraviolet photography and X-rays.

Through their work examining pigments, they discovered, for example, that a signed Pollock turned out to be a fake. They found acrylic on the painting, which wasn’t a medium available at the time the painting was dated and signed.

WCCFA’s office looks like a part art studio, part photography studio, part warehouse and part science lab. Chemistry is critical to the art of conservation — and various chemicals and solvents tables are spread throughout the space.

“One of the most important tenets of conservation is that anything we do to a painting is reversible,” said MacDonald-Korth.

The conservators use specialized stable materials and pigments that don’t deteriorate for long periods of time and that can be removed without harming the original paint.

Conservators use the “inpainting” technique to fill in where there are pigment losses, such as in cracks.

Conservator Camilla Van Vooren treats a landscape painting by Birger Sandzén, a Swedish-born painter who produced most of his work while living in Kansas.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

“We inpaint in just tiny dots because we don’t want to ever go over original paint,” said Camilla Van Vooren, one of WCCFA’s conservators.

“We don’t repaint because we never go over original material, and we don’t restore because we’re not trying to make the painting look better.”

Every work of conservation requires extensive documentation before, during and after treatment, including photography with professional lighting and written reports.

WCCFA charges $225 an hour and projects can range from $1,500 for a small project up to $50,000 for a large-scale painting with significant issues.

Sometimes people will ask MacDonald-Korth if conservation treatment will lower the value of a painting. She reminds them of Leondardo DaVinci’s “Salvator Mundi” that sold in 2017 for $450 million, shattering auction records.

“That one is majority work done by a conservator,” she said. “There was so much paint loss that it was almost like they had to invent what was there. And that painting sold for half a billion dollars. So the answer to that question is, ‘no.’”

MacDonald-Korth and her colleagues have been working on the Ribera painting for over a year.

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

Photo: Andrea Kramar, Rocky Mountain PBS

MacDonald-Korth and her team plan to complete their work on the Ribera painting by October 1, so Haas can show the work to Christie’s Auction House, which has agreed to fly to Denver and appraise “Deposition of Christ” in person once WCCFA’s conservation work is complete.

“He trusted his eye, and trusted his gut and he was right. It's incredible,” said MacDonald-Korth.

Despite the excitement over the Ribera painting, the art world is still a murky and risky place, and MacDonald-Korth warns buyers to never spend their entire life savings on a painting.

“All of this work could be done and still no one could buy it. That could be true, too,” she said.