Will building better help us weather the future? Marshall Fire victims hope so.

SUPERIOR, Colo. — The Sobti family watched their house burn down through their doorbell camera.

Amita Sobti and her family were vacationing in Mexico on December 30, 2021, when the Marshall Fire ripped through Boulder County. The black and white video from their doorbell camera showed a flurry of smoke and embers consuming the entrance to their home.

“And we were on a beach, I remember,” Amita Sobti recalled. “We were in disbelief. Like, ‘This can't be happening. We’ll be fine.’”

If only that were true. When Amita and her family returned to Superior five days later, they were greeted by ashes in their Sagamore subdivision. One car was left in what used to be the garage; the door had melted and fallen on top of the vehicle. Everything else was an indistinguishable pile of cinder surrounding the blackened foundation.

The Sobtis were not alone in this experience. The Marshall Fire destroyed more than 1,000 homes and businesses with spine-chilling efficiency. Two people died.

The cause of the blaze is still unknown. What is known, however, is that the conditions on the day of the Marshall Fire — arid landscapes combined with 100 mile per hour wind gusts — intensified the flames, making it the most destructive fire in Colorado history.

But it would be a mistake to treat the Marshall Fire as some unpredictable force majeure. Scientists agree that the combination of intense heat waves, increased drought and suburban sprawl means another fire like the Marshall Fire should not come as a surprise.

Looking back on the months preceding the Marshall Fire, Jennifer Balch said, “it was the warmest June through December on record across the Front Range going back to the 1960s.”

Balch is a fire expert and the director of Earth Lab at the University of Colorado Boulder. Because of climate change, she said, “fire season” — historically limited to summer months — is now a misnomer. “We can now have fires that are in the fall, in the winter,” Balch said.

Cenlin He agrees. A scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, He studies how climate change impacts drought, wildfires and snowpack.

“The snowpack serves as a natural water tower in the western U.S. and particularly in Colorado,” He said. Due to climate change, the snowpack is melting earlier, which He said “leads to drier and warmer summer conditions.”

Those conditions increase the threat of wildfires.

What can we do?

Research shows that more Americans are feeling powerless in their ability to combat climate change. It is an understandable feeling, especially considering statistics like this from the Carbon Disclosure Project: Between 1988 and 2015, more than 70% of global emissions were produced by just 100 companies.

Moreover, fossil fuel giants like Exxon have, for decades, emphasized the need for individual action vis-à-vis climate change, like recycling plastics. One might see it as an encouraging sign that corporations are taking the climate crisis seriously. The reality is much more sinister: knowing that individual action by itself was inadequate in the fight against climate change, those corporations still pushed that message of consumer responsibility, all while making billions of dollars selling plastics.

[Related: How Big Oil Misled The Public Into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled]

But just because the most impactful changes need to happen on a government and corporation level doesn’t mean people should start throwing away plastic. Individual action — particularly the influence individuals can exert through consumerism and voting — is still important.

Amita Sobti and her family, for example, are being intentional about how they rebuild their home in Superior.

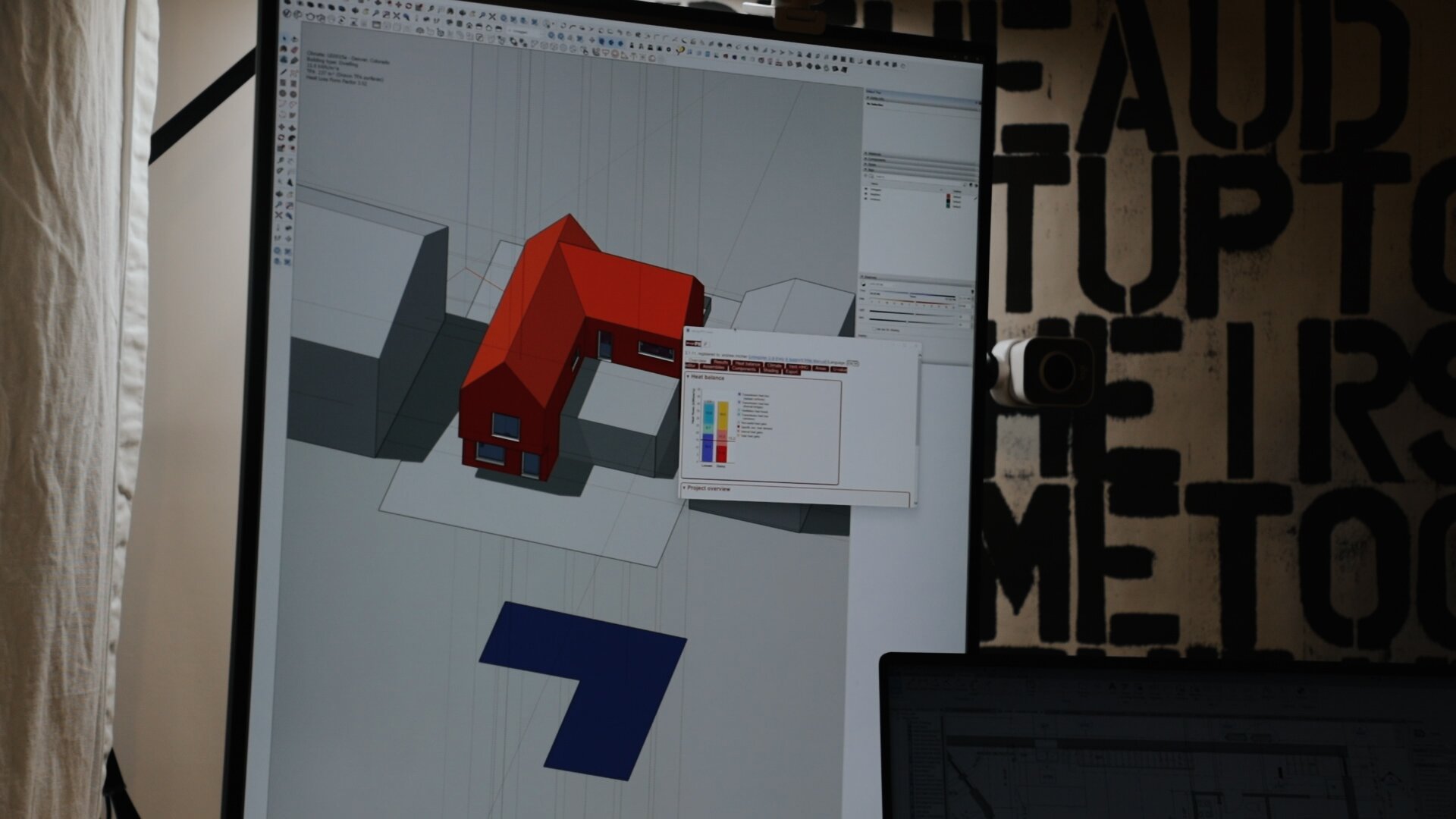

Enter Passive House, an energy efficient building standard that dates back to the late 1980s.

Simple designs and triple-pane windows make Passive House homes more fire-resistant.

Homes built to Passive House standards are extremely energy efficient, primarily through air-tight construction utilizing carefully designed doors, windows and walls as well as high-performance ventilation systems. Some Passive House buildings use 90% less energy compared to average new construction. To meet the standard, the building or home must meet strict criteria and be certified.

There is a secondary benefit to building a home to Passive House standards, one that the Sobtis appreciate: fire resistance.

Passive House homes are often designed as more simplistic structures. This helps with energy savings and makes the home harder to burn because there are more flat surface areas and fewer nooks and crannies for hot gasses to build up or embers to ignite.

The materials used in a Passive House design are more fire-resistant, including the siding and prefabricated walls. Finally, the air-tight aspect also protects the home by controlling smoke penetration as well as potential embers.

“There’s an old building science adage — ‘build tight, ventilate right’ — and Passive House really embodies these two principles,” said Zoe Kaufman. She is a research engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, focusing on energy efficient buildings, including Passive House constructions.

“I would really focus on air tightness and mechanical ventilation as the core reasons why Passive House is inherently good for building around fires,” Kaufman added.

The fire resistance of Passive House buildings

During wildfires, wind-blown embers often enter homes through broken windows and attic vents. By designing to Passive House standards — sealing off the home and avoiding traditional methods of ventilation — the embers have less of a chance to start a house fire.

Think of it as a campfire. If you’re starting with a match, it is much easier to burn a pile of kindling and small sticks (in this metaphor, a home with drafty windows, combustible materials and several nooks and crannies) than it is to set a whole log on fire (a Passive House).

Andrew Michler built the first certified Passive House in Colorado.

“We try to reduce those small points of where a fire can get into a building,” said Andrew Michler, a leading Passive House designer who built the first certified Passive House in Colorado

In 1991, Michler’s home in Oakland, California burned down. He related to the victims of the Marshall Fire; their stories inspired him to design a more affordable Passive House model specifically for people like the Sobtis.

A special kind of Passive House

Called the RESTORE Passive House, Michler’s design is a three-bed, three-bath home with a two-car garage. After homeowners take advantage of the incentives available to Marshall Fire victims, the RESTORE house tallies in at $550,000. (In February 2023, the median home price in Boulder County was $680,000.)

Unlike some people who are moving away from the charred neighborhoods of Superior and Louisville, the Sobtis decided to rebuild their home in the same location and they’re working with Michler to build a RESTORE house.

Amita told Rocky Mountain PBS part of her decision to rebuild was to show her kids the meaning of resilience. “You lose, you build again, and you build again better,” she explained.

The RESTORE Passive House is 2,600 square feet and was designed specifically for Marshall Fire victims.

But yet again, the responsibility to “build back better” is falling on individuals. In Colorado, “legislative efforts to make homes safer by requiring fire-resistant materials in their construction have been repeatedly stymied by developers and municipalities, while taxpayers shoulder the growing cost to put out the fires and rebuild in their aftermath,” ProPublica reported last year.

The Passive House, to Amita, was a no-brainer. “I do not trust the infrastructure anymore,” she said. “So [as] the whole climate changes, fires are imminent. And [Superior] is, in my mind, a fire prone area. Wind has always been very high and felt in the houses.” Boulder County officials said more than 40% of Marshall Fire victims are rebuilding to standards that will qualify them for rebates and incentives.

“As each house becomes more resilient to fire, it protects the neighbors. And the neighbors protect the neighborhood, and the neighborhoods protect the community,” Michler said. “So there's this kind of cascading effect. Every good decision making the homes better actually improves the entire community as a result.”

Kyle Cooke is the digital media manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at kylecooke@rmpbs.org.

Alexis Kikoen is the senior producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alexiskikoen@rmpbs.org.

Jeremy Moore is the content co-director at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can email him at jeremymoore@rmpbs.org.

Rocky Mountain PBS is partnering with NOVA on its “Climate Across America” initiative. “Climate Across America” is a national initiative that works to spotlight how climate change affects communities across the U.S. and engage audiences in productive conversations about innovative climate solutions. Learn more here.