As opioid crisis reaches new peaks, future of overdose prevention sites in Colorado remains unclear

DENVER — More than four years ago, Denver’s city council approved an ordinance that would allow for the creation of overdose prevention centers. Sometimes referred to as safe injection sites or safe consumption sites, these centers offer a safe place for people to use illicit drugs under the supervision of trained staff that can reverse overdoses and connect people with recovery resources, if necessary.

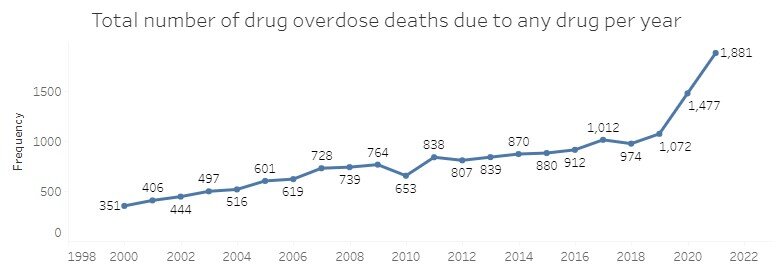

As the U.S. grapples with the worst overdose crisis in its history — nearly 1,900 people died from an overdose in Colorado in 2021, a record high — Denver still does not have an overdose prevention center.

The reason is because the council’s original ordinance was contingent upon the Colorado State Legislature passing a bill to allow the centers, which has not happened.

That could change this year.

A bill introduced in February would allow local governments, like Denver’s, to open overdose prevention centers. The primary sponsors for House Bill 1202 are Democratic Reps. Elisabeth Epps and Jenny Willford and Democratic Sens. Kevin Priola and Julie Gonzales. The legislation has more than 30 co-sponsors, which supporters see as an encouraging sign that it could pass.

“We love that bill,” said Lisa Raville, the executive director of the Harm Reduction Action Center. “It's the best bill in the legislature.”

Based in Denver, the Harm Reduction Action Center is the state’s largest public health agency that works specifically with people who smoke and inject drugs. Raville has been advocating for overdose prevention centers for years. In 2018, she delivered a TED Talk about the issue.

“I'm a service provider on the frontlines of the worst overdose crisis we've ever been in with the most unpredictable drug supply. I'm telling you, we need this,” Raville said in an interview with Rocky Mountain PBS. “We are crying out that we need this.”

How did we get here?

While there is no singular cause for the country’s current overdose crisis, national and local data show that the rise in synthetic opioids like fentanyl are driving the surge in deaths.

In 2011, 379 people died from an overdose involving opioids in Colorado. In 2021, more than 1,200 people in Colorado died from an opioid overdose. About 13% of the opioid deaths in 2011 involved fentanyl. But in 2021, that percentage was 72.5%.

Advocates like Raville say current policies, driven by the war on drugs, are clearly not fixing the overdose crisis in our country.

“We tried stigma, shame, incarceration, ‘Just Say No’ and D.A.R.E.,” Raville said. “And all that's done is bring us to the worst overdose crisis we've ever been in with the most unpredictable drug supply.”

[Related: Why "Just Say No" doesn't work]

For Raville, the logic supporting overdose prevention centers is simple: people will continue to use illicit drugs, so why not encourage them to do it in a safe environment where they can receive emergency medical care, if needed, and access to addiction treatment resources?

“So will we get everybody who’s using [drugs] in town? Absolutely not,” Raville acknowledged. “But we certainly know that people who are unhoused use outside, in alleys, in parks and in business bathrooms. And we want to take a lot of that out of the public sphere.”

What does the data say?

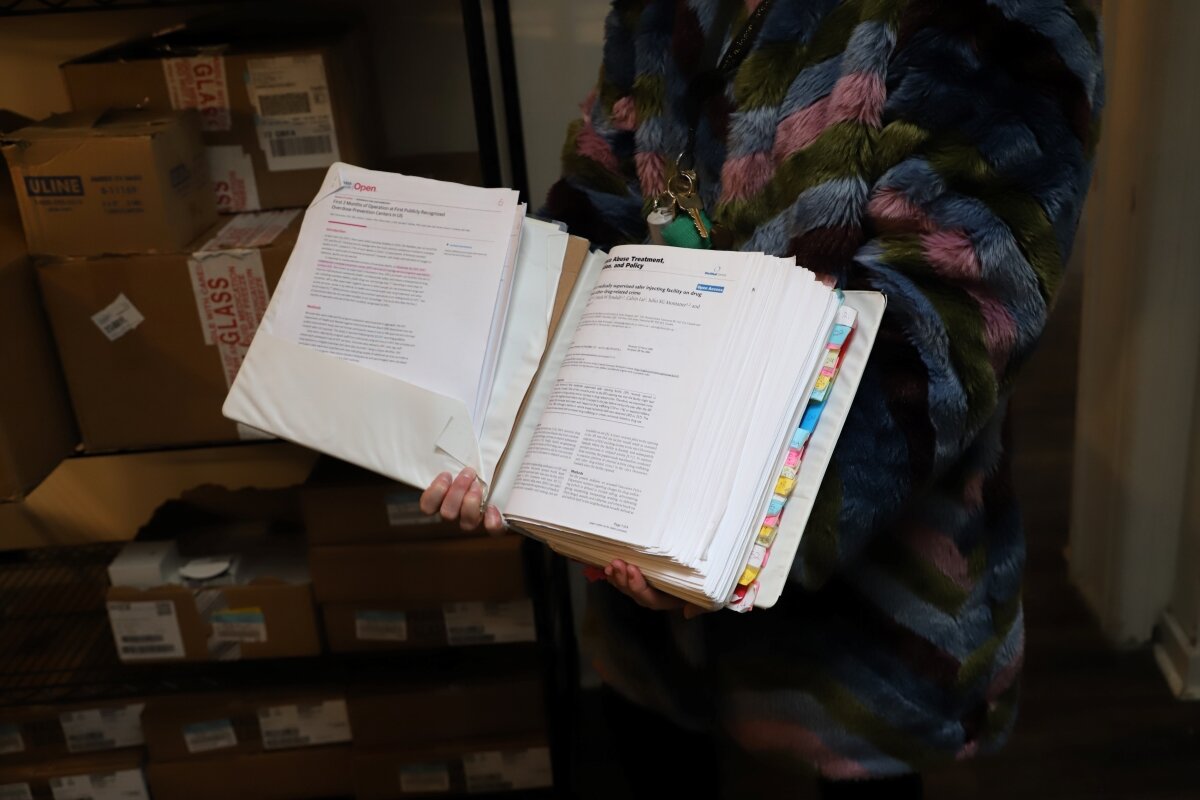

Raville, who is never far from her rotund three-ring binder of data supporting overdose prevention centers, said nobody has ever died at an overdose prevention center.

“The same cannot be said for Civic Center, Union Station, King Soopers, Starbucks,” Raville said. “It used to be cops coming up on people overdosing. Now it's 17-year-old baristas.”

Located in cities across Canada, Australia and Europe (and recently, in New York City), overdose prevention centers have been successful in reducing overdose deaths, limiting calls for ambulances and connecting users with addiction treatment resources.

In 2020, a report published by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review found that the centers “prevent overdose deaths and reduce overall costs by preventing emergency room visits and hospitalization.” The report also referenced three studies in Sydney, Australia that concluded that opening overdose prevention centers did not lead to an increase (or decrease) in crime.

The centers have also been successful in connecting users with resources. About 87% of the New York City overdose prevention center’s active drug users were connected to other services as well — addiction treatment, mental health care and job training, to name a few.

How do the sites work?

According to House Bill 1202’s text, the potential overdose prevention centers in Colorado would follow the model that has been established in places like Vancouver and Sydney.

Participants would bring previously obtained drugs to the center and use them under the supervision of trained staff who can recognize and respond to an overdose.

The Harm Reduction Action Center, which plans on becoming an overdose prevention center if the bill passes, has a mock stall set up in its offices that shows how the site might look.

Will the bill pass?

Both Raville and Sen. Gonzales, who represents Denver, praised the local control element of House Bill 1202. Under the bill, cities and towns would not be required to open overdose prevention centers; the bill simply gives them the ability to do so.

“Part of what we are seeing in Colorado is that the policies that are in place right now are leading to tremendous amounts of overdose and death,” Gonzales said. “Giving municipalities and local communities the ability to make their own decisions about whether and how they would like to look at overdose prevention sites — in order to keep people alive — that is really the root behind House Bill 1202.”

A couple big question marks remain. Whether or not Governor Jared Polis, a Democrat, will sign the bill (if it passes) remains unclear.

In a statement to Rocky Mountain PBS, the governor’s spokesperson said Polis “would be deeply concerned with any approach that would contribute to more drug use and lawlessness.” (Studies have not confirmed what some people call the “honeypot effect” — the idea that regulated drug consumption sites lead to or encourage more drug use.)

There is also the question of legal challenges; overdose prevention centers are technically illegal under federal law. But in 2022, Department of Justice officials told The Associated Press the department is “evaluating” overdose prevention centers and is looking into “appropriate guardrails.” Though not necessarily a ringing endorsement, the department’s stance was a marked difference from the Trump-era DOJ, which filed a lawsuit to prevent the opening of an overdose prevention center in Pennsylvania.

As for Raville, she understands that it can be difficult for people to go from “zero to overdose prevention center.”

“I get that,” she said, “which is why a lot of my job over the last few years in particular is showing folks exactly what's happening here and why we're asking for this shift.”

Raville concluded: “But we know that people use drugs. So how can we talk about safer and healthier ways today?”

Kyle Cooke is the digital media manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at kylecooke@rmpbs.org.

Julio Sandoval is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at juliosandoval@rmpbs.org.