Online enrollment grows in Colorado but some say more accountability is needed

When the pandemic first sent Colorado students home from school, Rachael Sheetz worried about the chaos of remote learning, but as the caretaker for her elderly grandmother, she also worried about COVID.

In her search for options for her two teenagers, she landed on Colorado Connections Academy, an online school. She figured they’d been doing online learning for a while and would be better prepared than traditional schools had been.

Today, 2½ years later, her son has returned to brick-and-mortar schooling at a popular local charter with high vaccination rates. But her daughter has stayed online, where she’s getting lots of teacher support and doing work that to Sheetz seems several grade levels ahead.

“I found that kids excel better when they can achieve academics at a pace that is comfortable for them,” Sheetz said. “My daughter has always been a decent student, but giving her more flexibility has helped her excel even more.”

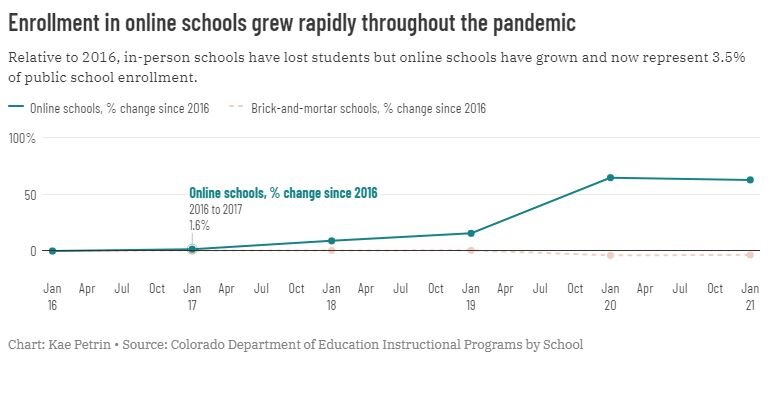

Enrollment in online schools in Colorado grew steadily before the pandemic, then surged as schools shut down in spring 2020, despite overall enrollment in public schools dropping.

In fall 2021, the most recent complete data available, Colorado enrolled 30,803 students in online schools, 50% more than the 20,603 enrolled in fall 2018. Online students now represent about 3.5% of public school enrollment.

Although online enrollment declined slightly from 2020-21 to 2021-22, officials expect more steady growth over time.

School districts, aware of families’ interest, are opening their own new online schools to meet the demand.

Yet much remains unknown about how online schools perform and how they’re managed.

One small district, Byers 32J, has increased its enrollment tenfold in the last decade by opening online charters. It now runs eight of them. That has increased its budget because the district keeps a portion of the state’s per student funds. Some of Byers’ schools posted the state’s biggest surges in enrollment and are the least transparent in data.

Statewide, seven in 10 online schools did not have enough data for the state to issue them a 2022 performance rating.

“It absolutely should be a concern,” said Van Schoales, senior policy director for the Keystone Policy Center. “The unfortunate irony is that online schools claim to be more connected to folks and yet a measure of connectedness is test participation and so it would suggest and reinforce a lot of the national research that online schools aren’t living up to advertising around personalizing instruction for kids.”

Related Stories

Schools meeting the demand

This fall, online school leaders say preliminary enrollment figures seem to show a slight dip again, but numbers still will be well above pre-pandemic levels.

Jeffco set up an online program last school year for families who weren’t ready to return to in-person classrooms, creating flexibility so that students could switch back and forth between remote learning during the year. This year, that program has converted into its own online school, here to stay.

Unlike the district’s Jeffco Virtual Academy, which has long existed, the new Jeffco Remote Learning Program school serves elementary age students too, and requires students to log in to receive live, real-time instruction from about 8 a.m. to 3 p.m.

At its peak last school year, the remote school had more than 1,300 students. This year, Principal Kala Munguia expects to have around 700 students. She said last year approximately 60% of students were enrolled because of pandemic health concerns, but this year students are more likely to prefer the learning model. Students who choose her school still want the live interactions every day.

“Our students tend to need or want that collaboration amongst other students,” Munguia said. She thinks more families will be interested in the model, once they learn it’s an option.

Adams 12 also set up a districtwide online program during the pandemic that now has turned into a new school, Five Star Online Academy.

Principal Adria Moersen said that the school was started in real time, or what’s called synchronous, but has since shifted to have more flexibility. Students can choose to be fully synchronous just for the mornings, or for certain days of the week, and now have more in-person opportunities for tutoring and other activities.

The school has about 520 students in grades 2 to 12, down from about 700 last year.

“This year these are students who are choosing online because it works for them,” Moersen said.

The district’s other online option is through Pathways, an alternative education school for older students off track to graduate. Before the pandemic, Pathways was a blended learning program that required most students to attend a few hours in person.

During the pandemic, the school tried allowing all students to be fully online, but found that it didn’t work for most students.

“Ours are students who really need that extra support,” said Principal Matt Schmidt. Still, this year, about 15% of students have been allowed to choose to stay fully online. The school’s model of six-week courses allows the students to opt to be online or in person for each six-week period.

District staff tout that flexibility as they try to reengage students who have left school. Moersen and Schmidt said that for some of their students, having to work or take care of family members means the online options work best.

When Sheetz chose an online school for her kids, she wasn’t sure it was going to work, but being a stay-at-home mom, she knew she’d be around to help them.

Sheetz was thrilled at the flexibility of being able to let her kids wake up later or take a break in the middle of the day to spend time together or run an errand. Still, she encouraged them to participate in some live classes at least once a week.

These are some of the same reasons families for years have chosen online learning. Bernie Zercher’s daughter’s social anxiety made it hard for her to participate in even the limited in-person programming that her siblings used as part of their home-schooling course. The biggest draw from GOAL Academy was more flexibility for her to participate live only as much as she wanted to, and that counselors and other available services could help her through her anxiety.

In four years in high school at GOAL, she’s become more comfortable with in-person activities and interactions, and now takes concurrent college classes in person, has an internship at the school’s multimedia department, and participates in a school music group.

“The GOAL setting was just so much more accommodating for her,” Zercher said. “I don’t know that that’s typical of online schools. I think it’s kind of unique to GOAL. They really were meant as a safety net for a lot of kids that had experienced childhood traumas or other issues.”

Growth makes accountability more important

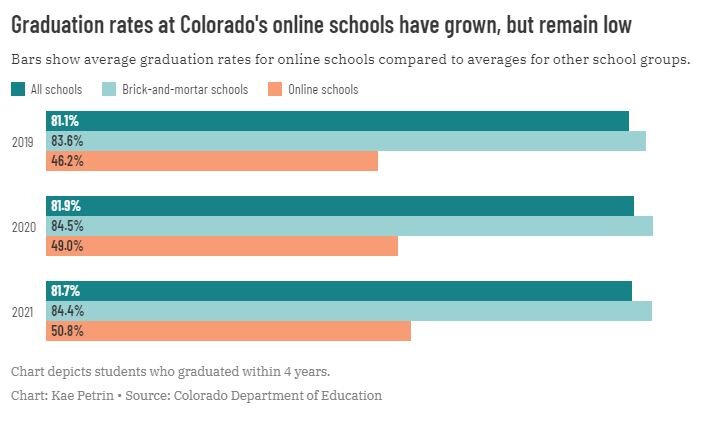

National data shows that online schools in general have lower student outcomes, including test scores and graduation rates, than do traditional in-person models. Studies of online learning during the pandemic also show students falling behind when they were learning virtually.

Of Colorado schools that tested enough students to report composite SAT scores publicly this year, online schools tested on average 25 points lower than brick-and-mortar schools, out of a 1,600-point maximum.

Of schools that tested enough students to report state CMAS scores publicly this year, online schools tested on average 5 points lower than brick-and-mortar schools on English and 21 points lower on mathematics, out of a 850-point maximum.

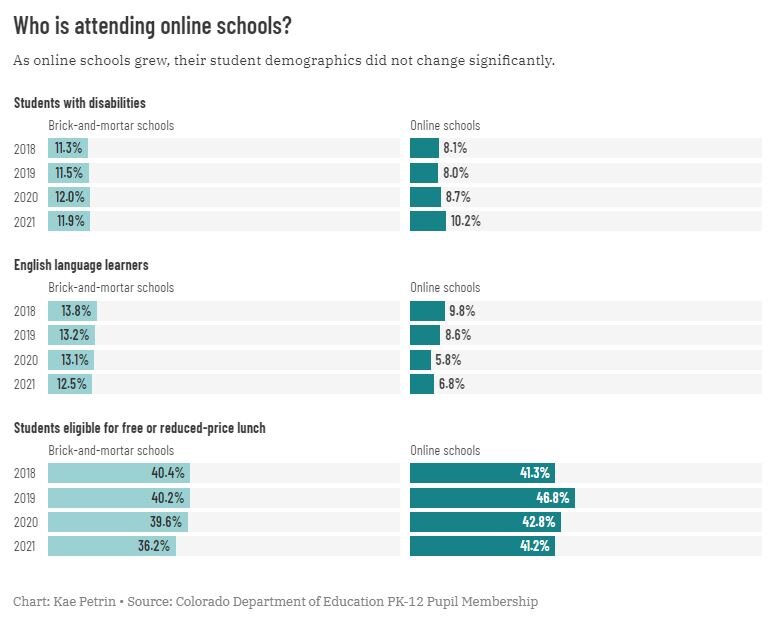

Advocates for online schools say that many students who seek an online education weren’t doing well in traditional settings, and may already be starting behind or facing other challenges.

But there also have been questions about the quality of education and how engaged online students are. Back in 2016, an Education Week investigation of GOAL Academy, which at the time was the largest online school in the state, cited internal school data that nearly half of students didn’t log in at all during a typical week.

Zercher isn’t just a parent. As a local business owner, he was tapped to serve on the board of GOAL as the school made much-needed reforms. He agrees with the need for more oversight.

“The whole charter school world is the wild, Wild West of education,” Zercher said. “I have seen some crazy stuff, and crazy disregard for regulations.”

Renee Martinez, supervisor for the state Education Department’s office of online and blended learning, says the state does its best to provide oversight, but has been limited by multiple changes in the law. Some issues are just relayed back to authorizers.

As it does for all schools, the Education Department audits student course loads and credits to ensure districts receive the right amount of money for students, and to ensure that students aren’t being counted as enrolled in more than one school.

There’s never been reason to believe that any school is falsely inflating their enrollment counts, she said.

But, “of course we operate on best intentions, thinking they wouldn’t do that,” she said.

Martinez said her department was also disappointed in how little data on performance there was for online schools this year. This year, online schools were more likely than brick-and-mortar schools to have insufficient data to earn a state performance rating — a growing problem among online schools.

Zercher agrees schools can do something about this and should be held accountable for it.

For example, he thinks that test participation reflects on the relationship of the school with its students.

In his daughter’s case, he said, she was willing to be at the state fairgrounds at 7:30 a.m. for testing because of the relationship with her counselor.

“She loves her counselor and doesn’t want to disappoint them,” Zercher said.

The elementary school affiliated with Colorado Preparatory Academy, an online school run by K12, a for-profit national provider, this year fell to the state’s lowest rating, known as turnaround status. Before the pandemic it had received the highest rating. But the principal cautioned that this year’s rating was based on 18% of students testing.

“This was the lowest participation I’ve seen,” said Nicole Tiley, executive director for Colorado Preparatory Academy.

She surveyed families who opted out and found the main reason families cited for not testing was concern about health and safety. “We are very proactively thinking about how to improve that,” she said.

The schools that have grown the most are the ones we know the least about

The school with the biggest enrollment increase since 2018, Astravo Online Academy High School, is one of eight schools under three brands, all under the umbrella of Colorado Education Solutions and authorized by the Byers 32J school district.

The Eastern Plains school district has made a business of authorizing online charter schools. Less than 10% of its 5,352 student enrollment attend its brick and mortar schools, while the other 90% attend one of its online charters. The district keeps 3% of state per-pupil money before passing on the rest to the schools.

Back in 2014, when the Education Department questioned Byers’ capacity to effectively manage so many online charter schools, Superintendent Tom Turrell wrote in a letter that his district was experienced, and that breaking up big K-12 schools into multiple schools would better help them evaluate how the schools were doing.

Years later, Turrell continues to defend the schools and deny that the large information gaps are problems.

The schools and their operator have existed under several names and brands since they first opened in the fall of 2012. The schools that have websites don’t list their principals or other staff or provide much information about the educational models. There’s just a phone number for a call center and a place to enter your email for more information.

According to a 2016 law, when schools change names, if they aren’t changing authorizers, meaning the district that oversees them, then they aren’t required to seek new state approval, even if they’re making significant changes to their management or learning model.

Since 2019, enrollment in Byers-authorized online schools has nearly tripled and those students now account for 16% of all the online students in the state.

In response to a public records request for the charter application and agreement between Byers and Astravo, Turrell initially said there was no contract. When the contract was provided by the state, Turrell said it had been a miscommunication. When asked again about the original charter applications, Turrell said he believed the application and the contract were one and the same. His school board did vote to approve the schools, he said.

Turrell said as an authorizer of eight multidistrict online schools, he’s not worried about the low participation rates on state tests and doesn’t feel there’s a lack of performance data.

Of the eight online schools authorized in Byers, none had enough data for state performance ratings this year, up from five of nine that didn’t have ratings in 2018. Colorado law requires state education officials to intervene in schools that have low ratings for five years or more, but the state cannot take any action when schools have insufficient data for years on end.

The district’s Astravo Online Academy High School, which experienced the state’s largest increase in enrollment among online schools from 2018 to 2021, hasn’t been issued a performance rating since 2016, in part because of low test participation. The school now has about 1,600 students.

“My kiddos are going to college, they are taking the SAT and PSAT very seriously,” Turrell said.

In fact, only 29% of Byers students pursued postsecondary education or the military after high school in 2021, compared with 55% statewide. Byers has lower-than-average test participation even among other online schools. Each of its online high schools had fewer than 10% of its eligible students take the SAT this year. Turrell said that he’s frustrated that students aren’t allowed to take state tests online.

“It really comes back to that opportunity to utilize an online platform,” he said.

Officials for Colorado’s Department of Education said that they’ve noticed that more schools overall this year had insufficient data to receive a performance rating, but officials haven’t looked into why online schools may struggle most with this, although they may in the coming months as ratings are finalized.

Turrell also doesn’t worry about Astravo Online Academy High School’s high withdrawal rate of 48.3%. In 2019-20, it was the highest in the state. These are students who leave school after the October count day. The school district still collects the money for these students but no longer has the expense of educating them.

The same state report shows that Astravo Online Academy High School also enrolls a lot of students after the state’s count day, even if the school doesn’t receive funding for them. In 2019-20, the school had 231 students withdraw and 622 enroll after count day.

“The data throughout the CDE mobility report are informed by the impact of those late-enrolling students,” Turrell said. “A thorough review of these facts is essential to consider when drawing conclusions.”

The Astravo schools in particular have high enrollment after count day, but most online schools, according to the report, also show enrollment after count day, and it’s also common among other schools.

Colorado Education Solutions has a limited public profile. A lawyer and a consultant for the group answered some questions, but could not point to where the charter network’s school board agendas, members, or meeting dates are posted online for the public.

The group, a charter network, is registered by attorney Brad Miller as a state nonprofit in good standing with the Colorado Secretary of State’s office. The charter network is not a federal nonprofit and doesn’t have to file a Form 990 that would disclose more information about its structure and finances, according to Mary Gifford, a consultant advising the charter network.

Open questions about online schools prompted lawmakers to pass Senate Bill 129 in 2019. The law aims to increase accountability for online schools by requiring that performance ratings follow a school even if it closes and reopens with a new name. It also requires the state to submit annual reports on how often students leave a school after count day, when enrollment for funding purposes is made official.

Martinez said the reports ensure State Board of Education members are more informed about online schools, but they haven’t led to much change.

“We implement the legislation and sometimes when there’s certain things like [Senate Bill] 129, it seemed like it was going to be maybe a game changer,” Martinez said. “In reality the impact wasn’t as significant.”

Yesenia Robles is a reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado covering K-12 school districts and multilingual education. Contact Yesenia at yrobles@chalkbeat.org.

Kae Petrin is a data & graphics reporter for Chalkbeat. Contact Kae at kpetrin@chalkbeat.org.